Understanding the Times: The Heart of the Reformation

Understanding the Times: The Heart of the Reformation

The Reformation of the sixteenth century is usually remembered for three things it emphasized: Sola Scriptura, Sola Gratia, and Sola Fides – the Scriptures alone, grace alone, and faith alone.

As for the Sola Scriptura, the Reformation marked a return to the Bible as the only authority for faith and life. But while Luther and the other Reformers took their stand on Scripture without compromise, their main emphasis lay not here. Rome also held to an infallible Bible. The problem was that Rome also held to an infallible church and placed too much value on tradition.

But the church did not need a Luther to tell her that the Bible was true. She did need him, however, to remind her what the truth of the Bible is. The distinctive contribution of the Reformation was its claim that the main purpose of the Bible, and therefore of theology, is to communicate the Gospel of forgiveness of sins and that salvation is by grace alone through faith alone.

Luther firmly believed that the key to the whole of Scripture was the doctrine of justification. These are his words:

"This doctrine is the head and the cornerstone. If the article of Justification is lost, all Christian doctrine is lost at the same time. It alone makes a person a theologian and enables him to distinguish and judge all other articles of faith."

Similar statements could be cited from Calvin's writings. A current theologian, J. I. Packer, says: "the doctrine of justification by faith is like Atlas. It bears a whole world on its shoulders, the entire evangelical knowledge of God and the Savior. When therefore Atlas loses his footing, everything that rested on his shoulders collapses too."

Similar statements could be cited from Calvin's writings. A current theologian, J. I. Packer, says: "the doctrine of justification by faith is like Atlas. It bears a whole world on its shoulders, the entire evangelical knowledge of God and the Savior. When therefore Atlas loses his footing, everything that rested on his shoulders collapses too."

But Luther and the other Reformers were not only convinced of the centrality of justification. They were equally sure of its meaning. For centuries justification had been confused with regeneration and sanctification. But what Luther came to see with increasing clarity was that one must make a sharp distinction between the righteousness which justifies a sinner and the righteous life or conduct of the justified believer. Luther understood justification to be a judicial verdict distinct from an act of inner transformation. In other words, he understood that God, in justifying a sinner, declares him righteous rather than makes him righteous. God imputes to the believing sinner the vicarious righteousness of Christ. He does not infuse into him the quality of righteousness. To be sure, He does the latter too, but that is sanctification, not justification. Although God's act of justification is inseparable from the believer's inner renewal and sanctification, these must not be confused with each other. Whenever that happens, believers are robbed of their comfort, and spiritual growth is impeded. Man is thrown back upon himself and his feelings, and Christ is lost sight of as the only ground of the sinner's acceptance with God.

If justification by faith is such an important doctrine we should not be surprised to hear that it has often been attacked by its enemies. These attacks have taken on many forms, but basically their aim is to destroy the forensic nature of justification. The sinner is declared or pronounced righteous in God's sight without any regard to his moral character. For about four hundred years Protestant scholars were virtually unanimous that the word "justify" (dikaion) means "to acquit or declare righteous" rather than "make righteous". Catholic scholars, on the other hand, were agreed that the word means not only "to declare righteous", but also "to make righteous."

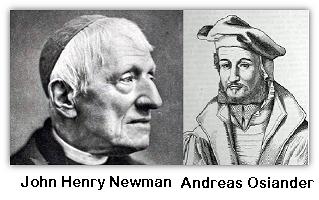

During the last fifty years many Protestants have started to adopt a basically Roman Catholic position on this point, while it seems that some Catholics are moving towards a Protestant understanding of justification. Notice that I say, "seems", because theologians like Hans Kung and others may sound like Luther, but they mean something quite different. James Buchanan says in his book The Doctrine of Justification: "it is almost impossible to invent a new heresy. Every attack on the doctrine of justification is represented by two men: Osiander and Newman."

Andreas Osiander was a German theologian who opposed Luther's doctrine of forensic justification after the Reformer's death. His basic thesis was that God would not commit the injustice of declaring a man to be righteous if there was nothing of righteousness in him. Osiander, therefore, contended that God must make a man righteous before He can declare him righteous. He proposed that Christ indwells the believer with His divine righteousness. This is what God sees, and seeing this righteousness of Christ in the believer, God pronounces him righteous in His sight. This view of Osiander is called in the history of doctrine "analytical justification", or a justification based on God's analysis of what the believer has become by grace.

Next we turn to John Henry Newman. This brilliant English scholar, who lived around the mid-nineteenth century, was first an Anglican, but later converted to Roman Catholicism. He is known for his attempt to make a synthesis between the Protestant and the Catholic positions on justification. Newman admitted that the word "justify" in Scripture means to "declare righteous". But, he argued, God's Word is a powerful word which creates what it declares. Newman used the creation analogy, where God said in Genesis 1: "Let there be light, and there was light". So, concluded Newman, when God declares the sinner righteous, that mighty creative word makes him righteous. Justification is therefore a declaring righteous which is also a making righteous.

Next we turn to John Henry Newman. This brilliant English scholar, who lived around the mid-nineteenth century, was first an Anglican, but later converted to Roman Catholicism. He is known for his attempt to make a synthesis between the Protestant and the Catholic positions on justification. Newman admitted that the word "justify" in Scripture means to "declare righteous". But, he argued, God's Word is a powerful word which creates what it declares. Newman used the creation analogy, where God said in Genesis 1: "Let there be light, and there was light". So, concluded Newman, when God declares the sinner righteous, that mighty creative word makes him righteous. Justification is therefore a declaring righteous which is also a making righteous.

Notice that while Osiander said that God declares righteous as a result of making righteous, Newman turns it around, saying God makes righteous as a result of declaring righteous. The end result, however, is pretty much the same. Both Osiander's and Newman's roads lead back to Rome, because in both instances sanctification is mixed up with justification.

All modern attacks upon Luther's doctrine of forensic justification are mere variations on a theme by Osiander and Newman. Especially the latter's.

Dr. Hans Kung is a recent exponent of Newman's position. This German scholar has written a book on justification that has influenced many Protestants, also Reformed Protestants. In this book Kung says: "Protestants speak of a declaring just which includes a making just, and Catholics speak of a making just which presupposes a declaring just. Is it not time to stop arguing about imaginary differences?" Many Protestants agree. There is a growing sentiment that the differences between Rome and the Reformation have been exaggerated and that we are a lot closer to each other than we have always been told.

This is a sad development, for it can only mean that Rome will benefit from it. Rome can live with Newman and Kung's synthesis and still be Rome. But Protestantism cannot accept this compromise and still be Protestant. Why not? Because any attempt to confound justification with either regeneration or sanctification cuts the heart right out of the Gospel. For what is the Gospel? That God justifies the ungodly (Rom. 4:5). But in Rome's view and increasingly also in the view of many Protestants, God justifies only those who prior to their justification have been renewed or sanctified, so that the basis for their being declared righteous is not solely the grace of God in Christ, but something good in man.

Let us not think it is only the Roman Catholics and those influenced by liberal theology who make the terrible mistake. It is also found among Arminians who have a tendency to make the faith whereby sinners are justified, a work which then becomes the basis for their acceptance with God. Others, for instance the Pentecostals, rely a great deal on emotions and feelings.

But even among staunch Reformed people like ourselves there is a danger that we fall into the same trap.

We have learned that the heart of the Reformation was its discovery that sinners are saved solely on the basis of the work of Jesus Christ. God declares those righteous who believe on the finished work of His Son, apart from any works or qualities of their own. God justifies the ungodly – this verse from Romans 4 sums up Paul's teaching on this great subject – and it was Luther who, like a second Paul, once again brought this key doctrine to the foreground.

The natural man hates this truth and therefore justification by faith alone has always been subject to fierce attacks. These attacks usually take the form of confusing justification with either regeneration or sanctification. Roman Catholics, and increasingly Protestants too, hold that a man is justified on the basis of faith in Christ plus his transformed life; his sincere sorrow for sin, a desire to serve God, a willingness to sacrifice for the cause of the Lord, etc. In my last article I said that we Reformed people are in danger of falling into a similar trap and I promised that I would explain what that trap is.

The natural man hates this truth and therefore justification by faith alone has always been subject to fierce attacks. These attacks usually take the form of confusing justification with either regeneration or sanctification. Roman Catholics, and increasingly Protestants too, hold that a man is justified on the basis of faith in Christ plus his transformed life; his sincere sorrow for sin, a desire to serve God, a willingness to sacrifice for the cause of the Lord, etc. In my last article I said that we Reformed people are in danger of falling into a similar trap and I promised that I would explain what that trap is.

The same Buchanan from whose book Justification I quoted, says that the most subtle form in which this error (seeking a ground in man) can appear is to substitute the work of the Holy Spirit in us or the work of Christ for us.

We commit this error whenever we look at the fruits of the Spirit in our life, such as sorrow for sin, humility, self-abhorrence, etc., and base our hope of acceptance with God on these experiences. But this is wrong. These experiences are evidences of regeneration or sanctification, but they may never be confused with justification. To do this is to fall back into the error of Roman Catholicism and other false teachings which detract from the work of Jesus Christ for sinners.

Even the work of the Holy Spirit, essential as it is to salvation, cannot be the basis on which God accepts us and declares us righteous. Why not? Because it is not a perfect work, whereas Christ's work is. As Buchanan says:

If we are justified solely on account of what Christ did and suffered for us, while He was yet on earth, we may rest, with entire confidence, on a work which has been already 'finished' – on a righteousness which has been already wrought out, and already accepted of God on behalf of all who believe in His name … Whereas, if we are justified on the ground of the work of the Holy Spirit IN us, we are called to rest on a work, which, so far from being finished and accepted, is not even begun in the case of any unrenewed sinner; and which, when it is begun in the case of a believer, is incipient only – often interrupted in its progress by declension and backsliding – marred and defiled by remaining sin – obscured and enveloped in doubt by clouds and thick darkness, – and never perfected in this life.

This does not mean that the Holy Spirit has nothing to do with our justification. On the contrary, the Spirit's work is as necessary for our justification as the work of the Lord Jesus Christ, but for different reasons. The work of Christ and the work of the Spirit must be clearly distinguished from each other because each addresses the human problem from a different perspective.

When Adam sinned he plunged himself and the whole human race into a twofold misery. We became guilty in the sight of a holy God and our nature came under the dominion of sin. Our guilt exposes us to God's wrath and the curse of the Law; while sin's dominion over us makes us slaves of our lusts and fills our hearts with enmity against God.

To be saved, both these evils must be removed. Our guilt must be atoned for, in order that God's wrath may be turned away and the curse of the law lifted. But also our love for sin and our enmity against God must be subdued so that we will serve the Lord again out of a motive of love rather than (slavish) fear.

From both these evils the elect are delivered by the work of Christ. As their Mediator He came to do whatever was necessary to secure not only their justification, but also their sanctification and all other spiritual blessings as well. By His active and passive obedience the Lord Jesus Christ satisfied God's law and paid the penalty due to us for transgressing its precepts, thus expiating or blotting out our guilt. But also – and this is very important in connection with our topic Christ also earned, as a reward for His labours, the Holy Spirit Who had been promised to Him by His Father. This gift of the Holy Spirit, Christ received in order that He might dispense it for the benefit of those for whom He died. It is the Holy Spirit Who as the Spirit of Christ regenerates sinners and brings them to repentance and faith. This work of the Spirit is absolutely essential. Without it no one will ever be saved. Yet we must be careful not to confuse the Spirit's work with that of Christ. The main difference is this: whereas Christ has procured or obtained all the blessings of salvation, it is the Holy Spirit who applies these blessings to God's elect. The work of the Spirit, therefore, cannot be the cause of our salvation. It is rather the consequence or result of what Christ has done to earn our salvation.

The Holy Spirit did not in any way participate in the work by which our redemption was obtained. This was Christ's work and His alone, and therefore that finished work of Christ is the only ground of our justification. That finished work of Christ is different from the ongoing work which He is still carrying on by His Spirit in the hearts and lives of His people.

That work of the Spirit of Christ consists mainly in bearing witness to Christ. The great subject of His testimony is Christ crucified and Christ exalted. As the Saviour Himself told His disciples shortly before leaving them: "The Spirit will glorify Me, for He shall receive of mine, and shall show it unto you." (John 16:14)

The Holy Spirit does not ask attention for Himself or for what He does, but He points us to Christ and what He has done. He opens our eyes for our sin and guilt and thus for the need of a Saviour. But having done this, He also reveals that Saviour to us in all His preciousness and all-sufficiency. As Paul says, He makes known to us "the things which are freely given to us of God." (1 Cor. 2:12) He bestows the gift of faith whereby we lay hold of Christ, so as to "receive and rest upon Him alone for salvation as He is offered to us in the Gospel." (Westminster Shorter Catechism, Q & A 86)

As Buchanan says:

This is the grand object of His whole work in conversion; to bring a sinner to close with Christ, and to rely on Him as his own Saviour. This result may not be effected without a preparatory process, of longer or shorter duration, in different cases; for the sinner must be convinced of his sin and misery and danger, before he can feel his need of a Saviour, or have any serious desire for salvation … But there comes a critical moment when he is effectually persuaded to receive and rest on Christ alone; and he is free to do so at once, for there is no barrier between him and Christ, except his own unbelief, or his own unwillingness. Receiving Christ by faith, he is united to Him; and being united to Him, he is complete in Him – Christ's righteousness becomes his for his justification, and Christ's Spirit becomes his also for his sanctification.

This being the case and Scripture is very clear on this point, why is it that we are so inclined to rest in something in us, even if that "something" is the fruit of the Spirit's work in our hearts, rather than in the work of Christ for us? The reason for this is that our minds are so depraved that if we are left to ourselves we will never accept Christ as the Father's free gift to us. We don't want to be saved by grace alone through faith alone. We refuse to be justified as ungodly sinners with nothing to present to God than our sins.

William Reed, another Scottish writer of the nineteenth century, wrote in his book, The Blood of Jesus: "Fallen human nature, when under terror, says, Get into a better state by all means; feel better, pray better, do better; read your bible more diligently; become holier, and reform your life and conduct, and God will have mercy upon you! But grace in the believer says, 'Behold, God is my salvation!'" Reed then makes this very important comment:

To give God some equivalent for His mercy, either in the shape of an inward work of sanctification, or of an outward work of reformation the natural man can comprehend and approve of; but to be justified by faith alone, on the ground of the finished work of Christ, irrespective of both, is quite beyond his comprehension. But 'the foolishness of God is wiser than men' (1 Cor. 1:25), for, instead of preaching holiness as a ground of peace with God, 'we preach Christ crucified' (1 Cor. 1:23), 'for other foundation can no man lay' – either for justification or sanctification – 'than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ' (1 Cor. 3:11); and, whatever others may do, in preaching the gospel, 'I am determined not to know anything among you, save Jesus Christ and Him crucified' (1 Cor. 2:2).

Since Christ, then, is the foundation-stone of our salvation, we must rest the salvation of our souls on His finished atoning work, and not on anything accomplished by us, wrought in us, or felt by us.

This is what the Spirit teaches all who are saved. Whatever convictions He may produce in you, whatever experiences you may have of His uncovering and awakening work, this must be the result: that you believe in Christ as your Saviour, or at least that you desire Him as your Saviour, and that your heart goes out to Him. If that is not the result, the Spirit has not done His work in you. For as Jesus Himself has said: "It is written in the prophets, And they shall all be taught of God. Every man therefore that hath heard, and hath learned of the Father (through the Spirit) cometh unto Me." (John 6:45)

Christ has done the mighty work;

Christ has done the mighty work;

Nothing left for us to do,

But to enter on His toil,

Enter on His triumph too.

His the labour, ours the rest;

His the death and ours the life,

Ours the fruits of victory,

His the agony and strife.

Add new comment