Calvinist Restrictions

Calvinist Restrictions

The Creative Response of Dutch Artists in the Golden Age⤒🔗

The destruction of paintings and statues←↰⤒🔗

In the eyes of the world, the Reformed faith seems to have little room “on its walls” for pictures. Its foundation is the Word. Great emphasis is laid on divinely-inspired Scripture, doctrine and preaching. The Protestant Reformers quickly gained their reputation, for distrusting the image, already in the decades following the publication of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses, in 1517. Zealots in the Reformed camp provoked the established Church of Rome greatly through iconoclasm. They went about destroying paintings and statues in churches, usually with some chaos and clamour. The great monetary loss grieved Rome, of course. At the same time the people felt deprived of the refinement and beauty of the art which had been violently eliminated. The most important issue was the threat to the traditional, devotional, use of pictures.

The Reformers however did not reject all visual art, but only the kinds of painting and sculpture commonly found in churches. These objects were being worshipped in contradiction of the second commandment. Altarpiece paintings became, for all practical purposes, disallowed in the Seven Provinces (today the Netherlands) after this time; they continued to be made only for secret domestic use. The country came to be dominated by the followers of Jean Calvin. Especially here, Calvin’s powerful influence put an end to what had formerly been a busy production of religious images. Lutherans, by contrast, were less severe. Luther himself reined in the rioting iconoclasts, in the early years of the Reformation. His followers would permit a limited use of paintings inside churches.

Jacopo D’Avoragine

The iconoclastic controversy centred on the content of works of art. Those altarpieces were attracting idolatrous worship, and later iconoclastic destruction, because they depicted certain persons. Most prominent were Mary and Christ, and then came Mary Magdalene, the apostles and evangelists, and lastly the more interesting and popular early Christian and medieval saints in the Canon. The heroic and miraculous deeds of the saints, mostly as they were recorded by Jacopo D’Avoragine in The Golden Legend, provided the subject material for countless altarpieces in churches and homes before the Reformation.

Calvin on images←↰⤒🔗

For centuries, it had become common practice to pray before, and to worship, such images. Rome developed a doctrine to justify this behaviour, claiming that it was not the image that was being venerated, but rather the original person whom the image depicted. This “reality behind the image” was called the prototype. A prototype, for example a saint, was being worshipped (this act was termed “latria”). The image itself was only being adored (“dulia”). This distinction was rejected by Calvin. In his Institutes he accused those who “adored” images, of worshipping them, idolatrously.

It is remarkable that Calvin then qualified his statements about images. He immediately went on to explain that other kinds of images, that were not typically worshipped, were acceptable and even desirable. It is but a short passage, in the enormous text of the Institutes:

I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible. But because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each, lest those things which the Lord has conferred upon us for his glory and our good be not only polluted by perverse misuse but also turned to our destruction... Let not God’s majesty, which is far above the perception of the eyes, be debased through unseemly representations. Within this class some are histories and events, some are images and forms of bodies without any depicting of past events. The former have no use in teaching or admonition; as for the latter, I do not see what they can afford other than pleasure.1

Of course pictures can delight the eye. How were they supposed to teach and admonish? Calvin cites the long-established type known as “history painting.” For such paintings an event, that contained a significant act, would be chosen. The possible choices were to be found in the texts of the Bible, ancient history, or even classical mythology (all of which fell under the category of “history” at this time). The moment would be shown in the picture, thus emphasizing the important deed. The painting would thus recommend this action, or warn against it. The most famous painting in this category is perhaps Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome which shows scenes from the Old Testament. Roman Catholic artists were also used to painting history paintings of the martyrdoms of saints, but these were precisely what Calvin did not have in mind.

Such history paintings were not for everyone. The commissioners were often elite, being educated enough to know the texts well (Greek and Roman history was still mainly available only in Latin). Calvin’s knowledge of this art also arose out of his own activity as a scholar. History painting was at the same time very expensive, because it demanded an educated artist who could also paint all things including gestures and the expressions on people’s faces. A modest number of history paintings appeared in the Netherlands during the seventeenth century. The City Hall of Amsterdam (now the Royal Palace on the Dam) was decorated with such paintings, whose themes emphasized morality in civic government.

Alongside history paintings, there were also many more representations of other subjects. These more popular works were usually cheaper to buy as well. They were less demanding of the artist’s abilities, and the viewer’s knowledge. They were typically less “edifying” (teaching), sometimes not at all. With few exceptions, they still adhered to Calvin’s restrictions on art.

Art in Calvinist Netherlands←↰⤒🔗

The question has already been posed by Volker Manuth, whether there were Calvinist artists who explicitly expressed their beliefs in their art.2 Jan Victors, a student of Rembrandt, seems to be an example: he refused to paint any pictures of New Testament subjects, because he would then have to depict Christ, in contravention of the second commandment. He was even mocked for his decision in a poem by the Roman Catholic Jan Vos. Victors’ guidelines were perhaps too extreme; they would have excluded his own teacher Rembrandt, and many others. In painting the events of the Old Testament he was actually taking part in a new trend in this country at this time. The first artists to do so had been Pieter Lastman (Rembrandt’s teacher) in Amsterdam, and the Leeuwarden-based Lambert Jacobsz. Neither of these two artists was Reformed (Lastman was Roman Catholic, Lambert Jacobsz. Mennonite). Rather than reflecting specific beliefs, these paintings simply appealed to Anabaptists, Mennonites and especially Calvinists who read the Old Testament on a regular basis. The Old Testament had become fashionable (people gave their children names such as Jacob, Abraham, Sarah, etc., for example) and these paintings filled the demand.

No new, single, definitive Calvinist art arose, at either the elite or the popular level. There was no call from the Reformers for painting to articulate their doctrine. Indeed, Calvin and his followers did not convey a great deal of artistic flair. They adopted a sober personal style. Their portraits show that they favoured plain black clothing (the dress of the American Pilgrim Fathers is a familiar example; it was the current fashion in Leiden, where they had been staying around 1620, before their departure for the New World). Depictions of church interiors show that the old decorations were covered in whitewash.

Such preferences did not agree very much with the luxury and beauty of fine paintings, but artists were able to adapt. They created sober paintings to sell to this public. It is the most obvious explanation for the shift from the colourful and rich paintings of before 1615 to a simple, monochromatic style in Dutch art in the decades following the Synod of Dordrecht of 1617-1618. Only after around 1650, in a climate of unprecedented prosperity, did Dutch taste in art favour the rich and lively again.

Rembrandt cannot be avoided, it seems, in a discussion of the Dutch Golden Age. His religious convictions have never been well-defined. He apparently did not join the Reformed Church, and associated with Mennonites as well as the Reformed. He was intensely interested in the Bible. He remains well-known for making history paintings, of stories from the Old Testament, and for steering his students in this direction. The tradition was carried through for about a hundred years, into the 1700s. It must be kept in mind that, even when it was most fashionable, Old Testament subjects only attracted the interest of a small and elite group; it was history painting, after all. The real explosion in new kinds of painting occurred on a more popular level, outside of this category.

Landscapes, seascapes and cityscapes←↰⤒🔗

At about the same time as the conservative Calvinists gained effective control of the Reformed Church in the Seven Provinces, a painting mania began in this country. For about fifty years, paintings were produced and sold in incredible quantities. A great artistic heritage emerged, which survives to the present day.

In this very favourable market, artists developed many new possibilities for pictures, by taking up many new kinds of subject material. Landscape and still-life especially flourished. Artists also introduced the seascape, the street scene, domestic interiors, church interiors, merry companies, the military company, the flower piece and the professions and trades, as themes for paintings. This variety replaced the narrowness of the spurned artistic tradition of the Church of Rome. The change reflected new restrictions, and new freedoms as well. Artists were freed to take up things previously considered too insignificant for a painting.

It surprises many people to learn that landscape painting as we know it only began in the early 1600s. It had been practised by the ancients, but abandoned in the Middle Ages. It was not considered worthy enough to be the subject of a painting. Artists would only use landscape as background to scenes of history. Curiously, in the 1500s these landscapes in Flemish painting were fanciful, usually consisting of wild and dramatic forests, and mountains. To the viewer it suggested that the story was taking place somewhere far away and unfamiliar.

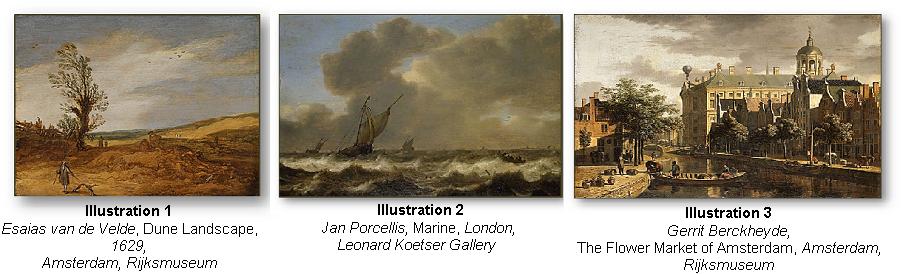

Haarlem artists such as Esaias van der Velde became the first to make paintings of local landscape again, in a realistic manner. They typically first made drawings from life, of views of the territory around Haarlem, where they lived (ill.1). The final painting was made in the studio. The artist would sometimes then deviate from the drawing, or even concoct a total fiction by assembling features from several drawings. It was still realism: convincing and taken from the real. Previously such “observed” landscape was only shown in drawings and prints. It became incredibly popular. Virtually every inventory of possessions in seventeenth century Amsterdam includes at least one landscape painting. Artists had found one good way to celebrate Creation and the rustic charm of the countryside, and even supply aesthetic enjoyment, while remaining completely clear before the second commandment.

The seascape started out quite differently than its cousin the landscape. Originally, artists were employed to make “portraits” of ships, at harbour or in battle. Merchants or naval commanders typically commissioned them. Beginning in the early 1620s, a much broader market was reached by artists such as Jan Porcellis. He painted marine views in which the sea and sky dominated, and the ships were mere accents (ill. 2). The “content” of such a picture was actually the weather: calm, troubled, or even violent. Viewers could then also reflect on God’s mercy in providing favourable weather for seafarers, and His sovereignty over their own lives as well.

The streets and canals of their cities and towns also attracted the attention of a number of Dutch artists. They typically did not favour picturesque older houses in their paintings, but rather chose newly-constructed canals, houses, and public buildings. These projects reflected the recent prosperity of the Netherlands. Many of the residents of this country at the time, especially in Amsterdam, were recent immigrants, refugees who had fled persecution in countries such as the Southern Netherlands (Belgium today) and France. Especially thousands of Reformed believers from Antwerp left their homeland bitterly, in the wake of a massacre in 1585 at the hands of the Spanish. Antwerp declined in wealth, its splendour decaying. At the same time Amsterdam became the new home for many of them, and its population multiplied several times as a result. Their capital, talent, experience, and hard work contributed heavily to the spectacular economic rise of this city. The crisp and detailed views taken in Amsterdam and Haarlem by the brothers Berckheyde, Job and Gerrit, reassured Netherlanders that God had blessed their steadfastness in faith, by giving fruit to their labour, and even affording them luxury (ill. 3). It was a materialistic idea about God’s favour that we would perhaps hesitate to take today, but one that was common in the seventeenth century.

Interior views←↰⤒🔗

Interior views usually had a very different emphasis: less on social status, and more on daily life. They often made some comment on lifestyle and morals. Such everyday scenes could thus have a serious symbolic meaning. Johannes Vermeer’s painting of a Woman Sleeping would have reminded the viewer of the vice of sloth, or laziness (ill. 4). It is not a shrill, severe sermon; there are no dire warnings that poverty or condemnation waits at the door. Instead this woman naps in affluence. There is perhaps a gentle reflection on the irony that material rewards sometimes lull a person into comfortable inactivity rather than spurring them into action. Vermeer’s extremely beautiful and calm arrangements often promoted some kind of moral message, though not always. Of the many painters who specialized in such interior scenes, he is by far the most famous. Even though he was Roman Catholic, Vermeer painted no altarpieces (that we know of), and his messages were almost always compatible with the Calvinism of his surrounding society, and of many of his buyers.

The daily activities in the paintings of Quiringh van Brekelenkam are even less pretentious. This artist made a number of pictures showing trades-people at work. They are usually inside their own homes, where many trades were carried out at this time. The atmosphere created by Brekelenkam in The Cobbler is quiet, and evocative (ill. 5). His style was sober, and lent dignity to his subject. Brekelenkam’s specialty was rare among painters. It appeared more commonly in prints. A little later in the century, Jan Luyken created a large series of prints of the vocations for a now-famous book devoted to the topic of work. Luyken was a strict Calvinist, and a poet, and the verses that he composed to these images frequently emphasize the Christian virtue of honest labour. This meaning likely also applied to Brekelenkam’s paintings.

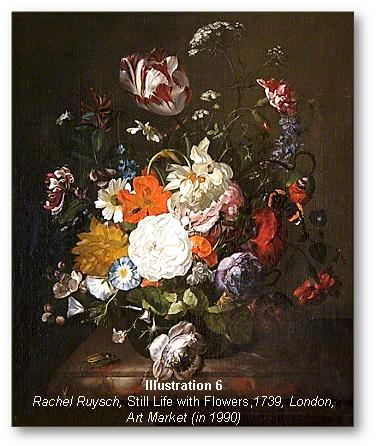

The paintings of flower-pictures occupied a great many women painters, as well as men. The pinnacle of achievement was perhaps the work of Rachel Ruysch, who developed very complicated, lavish and spectacular arrangements of colour and texture (ill. 6). She also kept up the tradition of scientific accuracy in clearly representing many various species. She is a late representative of this type of painting. The flower piece is yet another product of the Dutch Golden Age; it perhaps had its origin in Flemish paintings of “Madonna in the Wreath.” Around 1610 Ambrosius Bosschaert began to paint simple bouquets against plain backgrounds. Such pictures began as (pleasant) reminders that the life of man is as frail and passing as the blooming of a flower. As the tradition developed, this message became nearly lost in the display of beauty.

Painting flourished but not other art forms←↰⤒🔗

These and many other kinds of paintings arose in the Netherlands during its economic boom in the seventeenth century. Painting flourished in variety and quality. The country was very Calvinist, especially in its government, which excluded Roman Catholics and Mennonites. With a few well-known exceptions, artists did not risk provoking the authorities by painting pornographic paintings. Artists were not generally hampered by the Reformed restriction, that there would be no open public worship of images. Instead they turned to other kinds of subject matter. In some cases, the result was entirely new for art, in other instances it was something taken over from another art form, often prints. As shown above, serious moral reminders were incorporated into some works, but not others. This world of art was complex, even a little chaotic. Artists were freed from a fixed tradition and its burden of a narrow range of commissions.

While painting prospered, the same could not be said of poetry, music and theatre. These other arts fared much better in England, France, Germany, and Italy, during the same period. For example, the last internationally-famous Dutch composer for the organ was Jan Pietersz. Sweelinck (who was Roman Catholic). Organ music was attacked by many Reformed preachers, who for a time banned its playing during church services, and stirred up a great controversy. After Sweelinck’s death in 1621, his important followers were mostly German (Buxtehude, Bach), and the Dutch tradition faltered. With respect to theatre, it thrived in London (think of Shakespeare), but the Amsterdam Schouburgh (the poetic name given to the City Theatre) was repeatedly closed by the civil authorities, and even the great playwright Joost van den Vondel faced censure. Relatively few plays were written. In the case of both music and theatre, Calvin’s criticisms resulted in a general atmosphere of disfavour, which could be enforced through the public institutions of the church and the City Theatre. In contrast, painting took place in thousands of Dutch workshops and rooms. Painters who adapted to prevailing standards of a Reformed society simply outsold the dissidents.

Epilogue

After the “disaster year” of 1672, prosperity started to run out for the Dutch, and painting went downhill as well. Surprisingly, many of the new types of subject matter disappeared. This smaller market became dominated by a unified style, and a preference for elite subject matter. The new fashion was for an idealizing “classicism” (imitating the “classical” art from ancient Greece and Rome). It is discouraging to note the rise of the “rules of art,” which dictated this form of art as perfect, and denigrated all others. The great influence this time was not the Roman Catholic Church, but instead the Enlightenment in France, with its fascination for system, order and method. It was a situation similar to the previous dominance of religious images, in contempt of other subjects, which were not seen as “worthy” enough to be painted by artists. From our historical viewpoint, Calvin’s few simple restrictions seem to have provided Dutch culture with a liberating impulse to artistic creativity.

Add new comment