Jerusalem the Mother Church

Jerusalem the Mother Church

You could say that Jerusalem is the mother church of all Christians. That was where, on the day of Pentecost, it all began. The challenge, then, is to describe the apostolic period from the perspective of Jerusalem.1

To begin with, we will highlight the centrality of Jerusalem during the apostolic period, paying special attention to the written sources. After all, Jerusalem, the holy city, is the spiritual heart of the whole world.

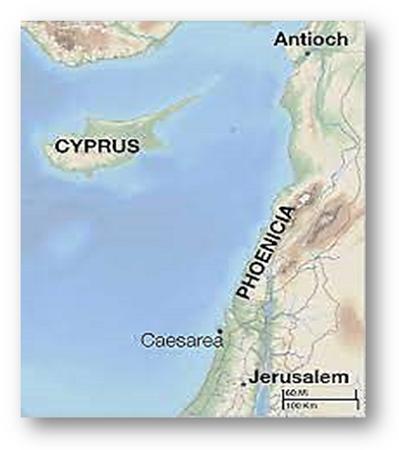

Second, we will examine the development of Jerusalem after Pentecost; with the northward flight of many believers as a result of Stephen’s death by stoning, the mother church gained a daughter in Antioch.

Finally we will explore Jerusalem as the mother church that distributes her bounty to her children by means of a number of letters: as a collection, the seven so-called ‘Catholic Epistles’ document the missionary progress that moves outward from Jerusalem. The Jerusalem perspective of two other non-Pauline books of the New Testament – Hebrews and Revelation – will also be considered. In doing so, we build up a picture of Jerusalem as the mother church.

The Apostolic Period⤒🔗

The twelve apostles, disciples of the Lord himself, were first of all charged to lead the church in Jerusalem, and to carry forth the gospel. They became ‘carriers’ in two senses: they themselves were the pillars of the gospel; they also had the task to carry the gospel out into the world, starting from Jerusalem. In this way, their voice re-echoed: for what the apostles broadcast was a news-making and much talked about gospel. Paul was a later addition to the number of the apostles: after ‘the Twelve’, he was the thirteenth and last: an extra labourer, so to speak, for external duties.

It would be difficult to provide a complete collection of biographies of the individual apostles. Of some of them we know virtually nothing. In this article the accent, therefore, will lie on the joint activity of the Twelve and those in their immediate circle. The course of their lives stood in service to their witness of Christ, Israel’s Messiah and the Saviour of the world. We have chosen to take Jerusalem as the redemptive-historical focal point, enabling us to gain a view of the gospel, as it was proclaimed and passed on during the apostolic period.

The ‘apostolic period’ is commonly understood to be the earliest phase of Christianity (in German: Urchristentum). Beginning in Jerusalem, the gospel creates ever-widening circles in the world, just as a stone sends out ripples in a pond. Some date the end of this period with the death of the last apostle, John; others see its end with the final separation of Judaism and Christianity, after the Bar Kochba revolt in AD 135. This coincides, more or less, with Eusebius’ description of the apostolic era: starting with the period after the Ascension (see the foreword to his Ecclesiastical History, II) and continuing till the reign of emperor Trajan. Eusebius comments: “We have now described the facts which have come to our knowledge concerning the Apostles and their times” (apostolikoon chronoon; Ecclesiastical History, III 31, 6; compare. II 14, 3).2

The two most important documentary sources for the apostolic period are the Book of Acts in the Bible and Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. We will examine each of them, providing a methodological account.

The First Source: The Book of Acts←⤒🔗

For the history of earliest Christianity we have access to a historic source in the form of a Bible book, with a more or less official title: The Acts of the Apostles. It is commonly accepted that Luke wrote this book, as a sequel to his gospel. Both Luke’s gospel and this sequel dealing with the apostles were dedicated to a certain Theophilus. Luke, who was not of Jewish descent (it seems likely that he belonged, just as Cornelius, to the circle of ‘God-fearing Gentiles’, adherents of the synagogue), had become a Christian, and a frequent companion of the apostle Paul. In narrative form, he recounts the spread of Christianity within the Roman Empire. Into this account, he integrates several discourses by the apostles. There can be no doubt that Luke, in writing this book, drew on a number of oral and written sources. In this way, his book became a coherent and well-attested whole.

From the perspective of the history of religion, the Book of Acts is unique. Of the other world religions, none has a comparable historical work, throwing light on its origins, that can be dated to its own time. Other religions may have narrative texts of a more legendary character; for the rest, the first history of these religions must be reconstructed by means of later material. By contrast, the Book of Acts provides us with a contemporaneous historical account.

Some scholars might attempt to weaken this conclusion with a claim that the Book of Acts is largely theological in character. Of course it is true that Luke, a believing Christian, had his own perspective on the church and the world. He makes horizontal as well as vertical connections. Hengel has rightly described him as a ‘theological historian’.3 Luke is writing redemptive history, but he does so in a way that does justice to its historical scholarship. In the preface to his gospel, Luke notes that he has carefully investigated everything from the beginning, so that Theophilus might know the certainty of the things he had been taught (ch. 1:4).

Research into the geographic and topographic information, the personal titles, and other details given in Acts has increasingly confirmed, after some initial scepticism, that Luke carried out painstakingly careful work. True, he has stylistically edited the apostles’ discourses, but without harming the authenticity of their content. In doing so, Luke follows the lead of the Greek historian Thucydides who, with his account of the Peloponnesian War, set the standard for the historiography of his time. Thucydides, in recording a number of discourses throughout his works, took great pains to represent the speakers’ lines of thought accurately, whenever a verbatim account was not available.

One must then, even if some questions might arise at specific points of detail, read the Book of Acts as a piece of serious historiography. This historical source is invaluable for our knowledge of earliest Christianity.

The Second Source: Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History←⤒🔗

Eusebius (circa 263-339 AD), who was a student of Pamphilius of Caesarea, and who later succeeded him as bishop, is often considered the father of church history. This is largely due to his monumental ten-part Ekklèsiastikè Historia, a marathon effort in which he “purposed to record in writing the successions of the sacred apostles, covering the period stretching from our Saviour to ourselves” (Ecclesiastical History, I 1, 1).

Eusebius painstakingly searched archives and libraries to find material from the first three centuries of the history of the Christian church. In contrast to the historiographical tradition that Thucydides and Luke followed, Eusebius includes very few addresses or discourses in his work. Sometimes he does insert older documents, or excerpts from them. For example, he quotes Flavius Josephus thirty or so times. Eusebius does not quote or refer to Jewish authors only: he also and especially draws on early Christian authors: Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Justin, Hegesippus, Origen and Dionysius of Alexandria. In addition, he refers to writers of the ancient classics, and the philosophical streams that flowed from them. Eusebius’ History, supported by source references and quotations, is a complex whole, mentioning a dizzying (for modern readers) array of names.

Of course, Eusebius is no modern historian. While occasionally he takes a critical view of his sources, to us he comes across to as being too credulous. He passes on stories that modern readers would find hard to believe. He comments in a fashion that betrays his own sometimes theological interpretation of events. He took the motif of truth from classical historiography as being synonymous with the truth of the gospel (Ecclesiastical History, I 5, 1).

All of this does not negate that Eusebius sets to work as a true historian, who bases his work on careful examination of historical sources, and who expects his readers to take him seriously. His Ecclesiastical History functions for us as the voice of someone who has a worthwhile contribution to make of his own, and who also allows earlier voices to be heard.

A continuing thread in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History is the apostolic succession throughout various congregations and regions during the first centuries of the Christian era. Eusebius regarded this as evidence of the guiding hand of God, leading eventually to the freedom Christians gained during the rule of Constantine. Eusebius considers the Christian church to be the special people of God in the world, as is evident from this passage:

For when the advent of our Saviour, Jesus Christ, recently shone forth on all men, it was confessedly a new race which has thus appeared in such numbers, in accordance with the ineffable prophecies of the date, and is honoured by all by the name of Christ, but it is not little nor weak, nor founded in some obscure corner of the earth, but the most populous of all nations, and most pious towards God, alike innocent and invincible in that it ever finds help from God.Ecclesiastical History I 4, 2; cp. X 4, 19-20: “Who established a nation never heard of since time began?”

Jerusalem, a World City←⤒🔗

Jerusalem would not be the first place to come to mind when thinking of a great world city. It really is no cosmopolitan metropolis, such as New York is today, or Rome was in antiquity.

Still, religiously, Jerusalem could be counted as a world city. It is the only place in the world that is known as the ‘holy city’. For centuries, it has been a place of pilgrimage for Jews, Christians and Muslims; at the same time it has always been a place of conflict.

Jerusalem has an extraordinary history. From of old, it was the city of the temple, and as such, the centre of the Holy Land.

Jerusalem was called ‘the holy city’ because that is where the holy God of Israel chose to dwell in His temple. It was the focal point of divine presence, not just in the Old Testament, but also in the New: ‘the city of the great King’ (Psalm 48:3; Matthew 5:35). Jerusalem was the place where Jesus of Nazareth was crucified, and where by the power of His Spirit, the first Christian community came into being. This is where the apostles proclaimed the gospel of their living Lord. From there, the apostolic gospel was carried outwards, into the world. Not only has Jerusalem had a remarkable history: it has also been promised a wonderful future. In the Bible, we discover the contours of a new city, one that will, according to the promise of God, unite heaven and earth.

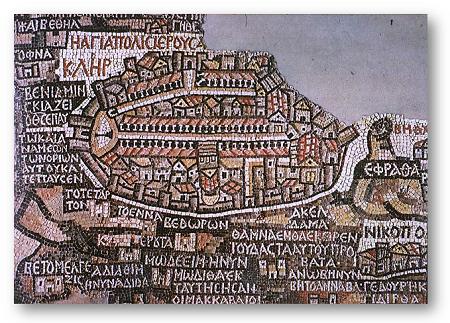

Mosaic←⤒🔗

The central position of Jerusalem is beautifully portrayed on the 6th century floor mosaic at Madaba, in Jordan. This topographical mosaic, with a floor area of around 30 square metres, was intended to map out the most notable places of the sacred history of Syria, Palestine and Egypt.4 Jerusalem, positioned in the centre, completely surrounded by a wall and lavishly furnished with gates, is larger than any other city. The same is true of its inscription, in large red script: ‘the holy city Jerusalem’. The city is in the shape of a perfect oval, and is clearly typified as the ideal city, the centre of the holy land, the navel of the earth (Ezekiel 38:12, compare 5:5 and the explanation of Acts 2:9-11, left).

In what is clearly a Christian representation, not only is the temple itself missing, but also the whole temple mount. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, traditionally the place – originally outside the city wall – of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial, has taken over the place of the temple complex in the heart of the city. Perhaps the floor mosaic of Madaba was intended to portray the New Jerusalem, the city of the future, in which there is no temple at all, “because the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple” (Revelation 21:22)

It Happened in Jerusalem←⤒🔗

In Luke’s twin volumes Luke and Acts, the city of Jerusalem takes a central role. Luke’s gospel, built up geographically, describes the movement of the gospel towards Jerusalem. In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke picks up the thread of the story again, starting in Jerusalem, and going out from there into the world. In this way, Jerusalem forms the geographic centre of Luke and Acts. More than that, the central position of Jerusalem symbolizes the theological point that salvation is from the Jews. Jesus is the Messiah of Israel, and at the same time the Saviour of the world.

To gain a clearer picture of the centrality of Jerusalem, the enumeration of peoples that we find in Acts 2 is a good place to begin. This is a list of God-fearing Jews, staying in Jerusalem, from every nation under heaven. These Jews from the diaspora were filled with utter amazement because of the spectacular events of Pentecost, especially perplexed because they heard all kinds of languages being spoken. Luke records them as saying:

Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs – we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!Acts 2:9-11

This list of nations is no random tally. The eye makes, as it were, a circular movement, centred on Jerusalem. This is true in both religious and geographic sense.

Let us examine the religious sense first: many commentators have already observed that this list does not represent the political situation of the Roman empire; instead, it encompasses the Jewish diaspora that had already taken place before this time, and it includes places which had never been part of the Roman empire. Luke shows his readers that there were Jews living throughout the known world.

Second, the geographic sense: one noteworthy aspect is that Judea is included in the list of nations. Luke is not referring to the immediate region of ‘Judea’, for in Luke and Acts this only occurs when Judea and Galilee are mentioned together. Rather, this is to be understood as encompassing the Jewish homeland as a whole, with Jerusalem as its capital; in later years, the entire Roman province was to be known as Judaea (Luke 1:5; 4:44; 6:17; 7:17; 23:5; Acts 11:29; 15:1; 28:21). Luke, in showing that Jews were living throughout the world, cannot leave out the Jewish homeland itself. Stronger still, Jerusalem and its surroundings are unmistakably the heart of the known world.

We may, then, conclude that in this list ‘Judea’ serves, as Bauckham has shown, as the geographic centre of the Jewish diaspora, a diaspora that fanned out in all directions.5

Luke points out that this entire diaspora was represented in Jerusalem at the miracle of the languages at Pentecost. They were “God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven”. From Judea, the geographic heart of the Jewish world, the eye turns first towards the east: Parthians, Medes, Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia. Then it turns northward: residents of Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia. From there it looks to the west: to Egypt, Libya and Cyrene; visitors from Rome, and Crete. Finally the eye turns to the south, to Arabia. The effect of this ordering is to show the readers that the place where the Spirit was poured out dominates the perspective towards all four points of the compass.

And to his audience, Peter says that their conversion will have worldwide effects: “The promise (he means the Spirit, promised by God and given at Pentecost) is for you and your children and for all who are far off – for all whom the Lord our God will call” (Acts 2:39). Far off, far from Jerusalem, in every direction of the diaspora throughout the world.

In other words: whether you are a Jew by birth, or joined to Israel as a proselyte, none who in any way belongs to the Jewish world can get around Judea, with Jerusalem as its capital and its centre. For Luke was only too aware, says Bauckham, that it was from the holy city that Christianity had spread in all directions. In this way, Jerusalem could be seen as the centre of the whole earth. That is where, on the day of Pentecost, it all happened!

We continue with a description of the development of the mother church Jerusalem, its relationship with one of its most prominent daughter churches, the church in Antioch, and the leadership role of the brothers of the Lord in the early church at Jerusalem.

The place where the first church gathered it happened, then, in Jerusalem. Where, exactly? Luke records that Jesus’ disciples, ‘stayed continually at the temple’ (Luke 24:53). Luke begins his second book, Acts, with an account of Jesus’ meeting his apostles (ch 1:2-4), and goes on to describe a subsequent meeting (ch 1:6: sunelthontes).

The implicit subject of v.12 is clearly the apostles, the ones who returned to Jerusalem after Jesus’ ascension from the Mount of Olives. In addition, ch 1:13 lists the eleven remaining apostles by name:

Peter, John, James (the sequence in the Majority Text is: Peter, James, John) and Andrew; Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew; James son of Alphaeus and Simon the Zealot, and Judas son of James.

The apostles had a regular meeting place in Jerusalem, an upstairs room where they usually stayed (v.13: to huperooion; compare Acts 9:37, 39; 20:8). We can think here of the time between the Ascension and Pentecost, days of expectation, fulfilled by the coming of the Holy Spirit. V.15 marks this period with the words ‘in those days’.

It is quite possible that this upstairs room was also where Jesus appeared after his resurrection, on Easter Sunday and the week following. Looking back a little further, we can think of the room where Jesus celebrated the last Passover with his disciples, a guest room somewhere in the city. In the other gospels, this room is described as a ‘large upper room’ (anagaion mega; Mark 14:15; Luke 22:12), fully furnished, containing at least three sets of couches surrounding a large table. Peter and James had been given the task of finding the unknown owner of this house, by means of directions Jesus had given them. In this room, apparently a place their Master liked, they had made the necessary preparations for the Passover meal. Had arrangements been made for a longer tenancy of this room, perhaps?

Even though a different terminology is used, this upstairs room in Acts is often identified with the upper storey described in Mark and Luke. (It is rather less likely that we ought to think here of a different upstairs room, located somewhere within the temple complex; it is not till Acts 2:46 that the temple is first mentioned). The article used in v.13 could well be used anaphorically, referring to a location already known to the readers of Luke and Acts.

Actually, an important historical argument may be advanced for this interpretation: archaeological research has shown that after Jerusalem was destroyed, a synagogue of Christian Jews was built upon the remains of this house. From there, various churches were established in Jerusalem. These days, tour guides point out the Coenaculum (the room of the Last Supper) as being located in a space above the traditional burial place of King David, in a 12th-century Crusader church in Jerusalem.

Eleven Remained←⤒🔗

After Judas’ death, eleven of the twelve disciples remained. They are all listed by name in v.13, beginning with Peter. Luke tells us that this gathering of eleven men ‘all joined together constantly in prayer’ (the Majority Text has ‘prayer and supplication’, v.14). This would certainly have included prayer for the promised Holy Spirit. Luke’s account shows that this wonderful unity, finding its expression in calling together on the Name of God, was characteristic for the Christian community in Jerusalem from the earliest, most tender stages of its existence (Acts 1:14; 2:1; 2:46; 4:24; 5:12).

Women were there too, Luke tells us in v.14. At first glance, we would be inclined to think of the women from Galilee, the ones Luke frequently mentions in his gospel as Jesus’ most devoted followers. There are, however two clues pointing in a different direction.

To begin with, the sentence lacks an article, leading Van Eck to make a point of translating this phrase as: ‘with women’ rather than ‘with the women’ or ‘with some women’.6 Nowhere does the book of Acts refer to women from Galilee.

Second, the Western text has added the word ‘children’ as well as an article, which indicates that the women meant here were also mothers of children. It seems reasonable, then, to think of the wives and children of the men listed by name in the previous verse. It is possible that not all of the apostles were married, but we know that Peter, for instance, took his wife along on his journeys (1 Corinthians 9:5). During the years that Jesus lived and worked on earth they had often, and for extended periods, left their families behind. Immediately after the Ascension, had the time perhaps come for family reunions?

If we follow this reading, v.14 lists two separate groups:

- the disciples, mentioned by name, together with their wives (and families);

- Mary, the mother of Jesus, mentioned by name, together with his brothers and sisters.

The physically absent Jesus, taken up into heavenly glory, brings these two core groups together. For both groups he forms the spiritual centre. The first group consists of his disciples and their immediate families; the second group is made up of his own immediate family: his mother, brothers and sisters.

This, by the way, is the last reference to Mary in the New Testament. She receives a place of honour among those remaining in Jerusalem, but increasingly she steps back into the shadow of her ascended Son, and eventually disappears from view altogether. In v.14, Mary is recorded as the mother of Jesus. Her Son, physically absent, but explicitly present in the text through his mother, is the real central character of this account. It was he who had arranged for this meeting place; it was he who had commanded his followers to go back to Jerusalem, and there to await what was to happen next.

Starting in v.15, a larger group of disciples comes onto the scene. The text gives us no reason to think of a different location. Apparently, the meeting place is still the same house, but an upper room would not have provided enough space to accommodate them all. Might they, perhaps, have begun to use the whole house (compare Acts 2:2)?

Luke relates how Peter began to speak, amid ‘the brothers’ (adelphoi in the Nestle-Aland edition, also the NIV and the ESV) or ‘the disciples’ (mathètai, as in the Western Text and in the Majority Text). The former highlights their relationship to each other: this group belongs to a spiritual family. This is the first time they are referred to as such in Acts. The latter focuses on their relationship to Jesus: this group is a gathering of his followers. This would connect well with the language usage of Luke and Acts. One way or the other, this marks the first beginnings of a congregation in Jerusalem. We are shown a fellowship which includes Jesus’ disciples, together with their families, along with all other disciples, in the broadest sense, both male and female. V.23 mentions two more by name: Joseph Barsabbas and Matthias. This situation is reflected in an expression that we find twice in Luke’s gospel: the Eleven and (all) those with them (Luke 24:9,33).

A Communion of Saints←⤒🔗

In Acts 9:31, the best manuscripts have ‘church’ (ekklèsia) in the singular. This can be explained by the word that follows: kath’holès: the catholic mother church of Jerusalem extends across a much larger area than the holy city itself: it can be found in Judea, Samaria and even in not previously-mentioned Galilee.7 In addition, Christian Jews travelled abroad, to bear witness across the diaspora of what God had brought about in Jerusalem (they went to Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch; Acts 11:19). It is to these people that James, the brother of the Lord, wrote his diaspora letter, to be followed later by the letter of his younger brother Jude. James’ address says: “To the twelve tribes scattered among the nations” (James 1:1).

Peter is often underrated, according to Hengel.8 Not only was he a passionate preacher; he also capably organized the church and acted as a missionary strategist. Unlike Paul, Peter does not revisit churches he has already planted; instead, after his journey to Samaria he makes a circuit through the plain of Sharon and visits the chief Jewish cities of the region: Lydda and Joppa. There, he meets ‘the saints’ (Acts (9:32, 41), an expression generally used for the believers in Jerusalem, sanctified by the Spirit (Acts 9:13; 26:10, compare also Revelation 20:9 and Paul’s reference in Romans 15:25-26, 31).

Peter, then, was visiting the outlying districts of the one church of Jerusalem. Within the church there was great encouragement, thanks to the healings he performed in Lydda and Joppa. Outside the church, the effect of Peter’s visit was that those who lived in Sharon turned to the Lord. An example of missionary activity among the Jewish people!

Antioch, the Daughter Church←⤒🔗

The second Christian church only comes into existence when the people of Antioch become acquainted with the gospel of Jesus Christ. This happens when men from Cyprus and Cyrene, some of those who had been scattered by the persecution in Jerusalem, come into contact with the Greek inhabitants of Antioch (probably beginning with those among them who were ‘God-fearing’).

Again, the church in Jerusalem keeps a close eye on this development. When the news of what has happened reaches them, they wish, just as in Samaria, to retain control of events. This time, it is Barnabas, a bridge-builder par excellence, who is sent to investigate. Barnabas, tells Luke, was a good man and full of faith, well trusted by the church in Jerusalem (Acts 11:24). Having his own roots on the island of Cyprus (Acts 4:36), he was the right person to assess what the Cypriot and Cyrenian brothers had achieved in Antioch. On his arrival, Barnabas encouraged (parekalei) them all to persevere, and to remain true to the Lord. Barnabas was also the one who introduced Saul – just as he had previously done in Jerusalem – to the church in Antioch.

By a spontaneous process, this is where believers are first called christianoi (Acts 11:26b; compare Acts 26:28 and 1 Peter 4:14): here, the Christians, disciples of Christ, form an independent community.

From that time on there is, alongside the mother church in Jerusalem, a daughter church in Antioch, consisting of not only Jewish but also Gentile Christians (here too, the singular ekklèsia is used: Acts 11:26; 13:1; 14:27; 15:3). Apparently, this church is under the leadership of prophets and teachers, five of whom (just as the Twelve and the Seven) are mentioned by their full names: Barnabas, Simeon Niger, Lucius the Cyrenian, Manaen, and Saul (Acts 13:1). Increasingly, the daughter in Antioch begins to show marks of adulthood, and eventually becomes an independent church, full of missionary vigour.

What was the relationship between the mother church in Jerusalem and her independent daughter in Antioch? There was always a risk that they would grow apart. Each of them had their own character: Jerusalem was exclusively Jewish, while Antioch was partly Gentile also. In Acts 11-15, Luke repeatedly points out that these two Christian churches, intimately woven together by a common past, consciously aimed to find a way together once the work of mission among the nations began to expand.

Frequently, delegations were sent from the one church to the other. A number of prophets travelled from Jerusalem to Antioch to pass on their message, or to deliver and further explain a letter. Antioch provided financial help to Jerusalem for the support of brothers and sisters during a period of famine. Antioch, not Jerusalem, became the home base for Paul’s missionary journeys; even though Paul was not from the church in Jerusalem, some of his first missionary colleagues were – Barnabas, John Mark and Silas (see also Acts 11:22,27; 12:25; 13:4-5; 15:22,40). Mission work among the Gentiles, therefore, was not a typically Antiochian enterprise; it remained anchored in the mother church in Jerusalem.

James and the Elders←⤒🔗

With Peter’s departure, the leadership of the church in Jerusalem fell to James. In the New Testament, he appears more than once as a church leader (Acts 12:17; Galatians 1:19, James 1:1). This brings to the fore a category of men less well known than the apostles: the brothers of the Lord. Still, the New Testament does tell us something about the role Jesus’ blood-relatives played in the New Testament church.

At the beginning, Jesus’ own brothers did not believe in him (John 7:5). It seems, however, that his appearance as the risen Lord, especially to James, brought about a change in their attitude (1 Corinthians 15:7). Together with their mother Mary, Jesus’ brothers formed part of the early church in Jerusalem (Acts 1:14). Later, next to the apostles, the Lord’s brothers played an active part in the proclamation of the Gospel. It appears that James, the eldest, remained in Jerusalem, while the younger brothers Joses, Simon and Jude (Matthew 13:55; Mark 6:3) are believed to have made missionary journeys of their own. In contrast to Paul, however, they were accompanied by their wives, who themselves were among the believers (1 Corinthians 9:5).

In addition, two letters in the New Testament canon, sent to Jewish Christians, have the names of Jesus’ brothers in their address: a diaspora letter by James himself, and a follow-up letter written by his brother Jude. Neither of them, however, present themselves as the Lord’s brothers; rather, as his servants. Jesus is our Lord and Master, no less (James 1:1; Jude: 4).

The devout lifestyle of James, who daily prostrated himself in the temple to plead for forgiveness for his people, evoked such respect that he became known as ‘the Just’, i.e. the Righteous (Eusebius, Ecclesiatical History, II 1, 2-5; 23, 4-7).9 He was indeed a tsaddiq in the fullest sense of the word. And because Jerusalem was regarded as the mother church for all of Christianity, James was held in high esteem even well outside the boundaries of the Holy Land (compare Galatians 2:12).

The Gospel of Thomas contains an apocryphal saying of Jesus, which could well be taken as a witness to the universally respected righteousness of the brother of the Lord. When the disciples wondered who should become their leader after Jesus left them, he is supposed to have said: “Wherever you are, you are to go to James the righteous, for whose sake heaven and earth came into being”. What the rabbis said about the Torah, applied to James also, throughout the world.

After James’ violent death, he was succeeded as leader in the church of Jerusalem by another of Jesus’ relatives: Simeon, the son of Cleopas, known to us as one of the travellers on the road to Emmaus. Hegesippus describes Cleopas as the brother of Joseph, Mary’s husband. If that is so, Simeon was a first cousin of Jesus (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, III 11; IV 22, 4). In addition, two of Jude’s grandsons, arrested by Domitian because of their Davidic ancestry and later released, have played an important role in early Jewish Christianity.

The bishop’s seat, symbol of James’ position as leader, was an object of interest right up to Eusebius’ day. From the quotation below, it is clear that in the first centuries of church history, the Holy See was not in Rome, but in Jerusalem:

Now the throne of James, who was the first to receive from the Saviour and the apostles the episcopate of the church at Jerusalem, who also, as the divine books show, was called a brother of Christ, has been preserved to this day; and by the honour that the brethren in succession there pay to it, they show clearly to all the reverence in which the holy men were and still are held by the men of old time and those of our day, because of the love shown them by God.Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, VII 19

Nevertheless, we do not get the impression from the book of Acts that after the apostles’ departure, the leadership of the church narrowed to one person. In the company of James, a number of elders suddenly make their appearance (Acts 11:30; 21:18). Already at the council in Jerusalem they are mentioned in the same breath with the apostles (Acts 15:2, 4, 6, 22-23).

No Particular Moment←⤒🔗

In contrast to the Seven (Acts 6:5-6), or the elders of the Pauline congregations, we do not read of a particular moment when these elders were chosen or appointed. Apparently, these men were not elders in the sense that they had been put forward from within the churches. Their authority was self-evident. They derived it from the life experience that came with being an older member, in this case from their special first-hand experience of having known Jesus Christ personally, and of having been sent out by him (perhaps as one of the Seventy: Luke 10:1-20).

Hence the almost automatic connection, between these elders and the apostles. Van Bruggen compares their position in Jerusalem with that of the elders of Israel, the ones who had witnessed the entry into the land of Canaan, and who had outlived Joshua. After Joshua’s death, these men remained as living eyewitnesses of what God had done for Israel (Joshua 24:31; Judges 2:7). Similarly, the elders in Jerusalem were living eyewitnesses of what God had done in Israel through Jesus Christ, his own Son.

These eldest disciples of Jesus formed a college, of which, so to speak, James was the chairman. Within the church of Jerusalem, ‘James and the elders’ have a position of authority, as the Book of Acts shows. They have custody of the diaconal funds collected for the church (Acts 11:30). During the Jerusalem council the elders, with James as their spokesman, stand beside the apostles.

The decision of this council, as described in Acts 15, has been of immeasurable value for the relationship between Jewish and Gentile Christians. You do not need to be a Jew to be allowed to belong to the God of Israel!

Later, the elders gathered around James to receive Paul and his companions; their joint declaration is then expressed in the first person plural: ‘we’ (Acts 21:18-25).

If Bauckham is correct, the early Christian tradition has preserved the names of the elders of Jerusalem.10 In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius lists fifteen Jewish overseers, continuing up to Hadrian’s campaign after the Bar Kochba revolt. The list begins with James, the brother of the Lord; then follows Simeon and Justus; then another twelve names. The number fifteen seems rather artificial, since later Eusebius lists another fifteen Gentile overseers, for a round total of thirty. Eusebius’ explanation for the large number, that they each lived for only a short period, is hardly convincing, since it is known that Simeon lived to a very old age.11 It is far more likely that the overseers listed did not succeed each other, but were each other’s contemporaries, sharing the leadership of the church in Jerusalem. If we regard Simeon and Justus as James’ direct successors, we are left with precisely twelve: Zaccheus, Tobias, Benjamin, John, Matthias, Philip, Seneca, Justus, Levi, Ephres, Joseph and Jude. These twelve men are likely to have formed the college of elders who, together with James, gave leadership to the church of Jerusalem.12

The final instalment continues with an overview of the place and contents of the seven Catholic Epistles in the New Testament, and concludes with a brief examination of the significance of Jerusalem in the letter to the Hebrews and the Book of Revelation.

We continue with an overview of the place and contents of the seven Catholic Epistles in the New Testament, and concludes with a brief examination of the significance of Jerusalem in the letter to the Hebrews and the book of Revelation.

Jerusalem Distributes its Bounty←⤒🔗

Having recounted, in his second book, the events that took place after the ascension of Jesus Christ, especially those in the church at Jerusalem, Eusebius begins the third book of his Ecclesiastical History as follows:

Such was the condition of things among the Jews, but the holy Apostles and disciples of our Saviour were scattered throughout the whole world. Thomas, as a tradition relates, obtained by lot Parthia, Andrew Scythia, John Asia (and he stayed there and died in Ephesus), but Peter seems to have preached to the Jews of the Dispersion in Pontus and Galatia and Bithynia, Cappadocia, and Asia, and at the end he came to Rome and was crucified head downwards, for so he had demanded to suffer. What need be said of Paul, who fulfilled the gospel of Christ from Jerusalem to Illyria and afterward was martyred in Rome under Nero? This is stated exactly by Origen in the third volume of his commentary on Genesis. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, III 1, 1-3

In drawing on this tradition here, Eusebius aims to give an insight into the worldwide spread of the apostolic proclamation. The movement went from Jerusalem to all points of the compass, with Rome becoming the new centre of the world.

This tradition, according to which Thomas, Andrew and John were each assigned a region, ought not to be understood as if the apostles, by mutual agreement, parceled out areas of labour; rather, it points to a divine appointment of tasks from heaven (Greek eilèchen: received by lot). Eusebius wants to show how the emissaries and disciples of Jesus Christ, through their missionary journeys, gave concrete form to the world-wide spread of the Gospel. This is how both Peter and Paul, neither having planned their missionary itineraries, but led by the hand of God, found their way to Rome. The other traditions, of greatly varying quality, and often largely beyond verification, are not inconsistent with this general picture.

The tradition that Eusebius draws on shows that while Paul, may be considered the best-known of missionary apostles, he is certainly not the only one to have made such journeys.

Geographic details of Peter’s activities among the Jewish diaspora are no doubt based on the address of Peter’s first letter (1 Peter 1:1). The letter itself, however, leaves the impression that other preachers had been active in Asia Minor (1 Peter 1:12), while Peter himself stayed in Babylon (ch 5:13). He is also known to have travelled to Antioch, witness his confrontation with Paul there (Galatians 2:11).

In addition there are three indications that the apostle Peter, perhaps accompanied by his wife, is likely to have visited the city of Corinth. In the first place, it was Peter who had fanatical supporters in Corinth – a true ‘Cephas party’ (1 Corinthians 1:12). Second, Paul uses the example of Cephas to demonstrate to the Corinthians that apostles had every right to take their believing wives along on their journeys, even though Paul himself does not do so (1 Corinthians 9:5). Third, Dionysius, the bishop of Corinth, writes a century later that both Peter and Paul were involved in the establishment of the church at Corinth. Both apostles, records Dionysius, have planted in Corinth, and have given further instruction there as well (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, II 25, 8).

Seed-pod←⤒🔗

It seems clear that the church at Jerusalem resembled a bursting seed-pod. The seed of the gospel scattered across the face of the earth. Twelve plus one sower knew themselves called to take the lead. And while it is true that this scattering of seed was done first by the emissaries and disciples of Jesus Christ, beginning in Jerusalem and spreading throughout the world, this activity was not limited to them. The brothers of Jesus and other passionate preachers took an active part in this proclamation of the gospel. The power of the Holy Spirit set an immense missionary movement in train. In this way the church of Jerusalem, where everything began on the day of Pentecost, became a truly catholic church in the full meaning of the word: universal, a Christian community of faith that – spiritually – extended all over the world. This global catholic church has its roots, not in Rome, but in Jerusalem!

Seven Catholic Epistles←⤒🔗

‘Catholic Epistles’ (or ‘General Epistles’, as they are sometimes referred to,) is a collective term for a group of seven letters that bear the names of their authors only, and not those to whom they were addressed. Traditionally, these letters are ascribed to James, Peter, John and Jude. In some later manuscripts, the word ‘catholic’ was sometimes added to their superscription. Hence: the catholic epistle of James, etc.

Many modern commentaries and handbooks do not deal with these letters as a unified whole; instead, after covering the gospels, the Pauline epistles and the Johannine writings, they assume that what remains is a random assortment of left-over letters. At the time of the fourth-century church fathers, however, published lists of the canon grouped these as a collection of seven so-called Catholic Epistles, each of them identified by name.

The manuscript tradition of the New Testament displays a remarkable phenomenon in relation to these letters. In the great majority of manuscripts, they immediately follow the book of Acts, before the Pauline letters, even. We see this in the codex Alexandrinus, the codex Vaticanus, the codex Ephraemi Rescriptus as well as in the Majority Text. The book of Acts, and the Catholic Epistles have a very close connection.13 In the Greek canon we see the same thing. It is only under the influence of the Latin tradition (as laid down in the text of the Vulgate) that the Pauline letters precede the Catholic Epistles for the first time.

Bearing in mind that the attention of the Western European reformers was largely directed towards Paul’s instruction concerning justification by faith, it must be said that in the study of the New Testament, the Catholic Epistles have often been overshadowed by the letters of Paul.14

Fourth Century←⤒🔗

In the fourth century, when describing the death of James, the brother of the Lord, Eusebius mentions seven missionary letters. The first of these was written by James; his brother Jude is understood to have written one of these seven also. There were some doubts about James. Not about its content, apparently, for it was freely used in the churches; but there was some uncertainty as to its authorship. The ancient authors that Eusebius consulted could provide no definite answer to this question, nor about the letter of Jude. Still, after some initial hesitation, the churches accepted the authenticity of the seven Catholic Epistles, and with it the recognition of James as author. Eusebius writes as follows:

Such is the story of James, whose is said to be the first of the Epistles called Catholic. It is to be observed that its authenticity is denied, since few of the ancients quote it, as is also the case with the Epistle called Jude’s, which is itself one of the seven called Catholic; nevertheless we know that these letters have been used publicly with the rest in most churches. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, II 23, 24-25

Elsewhere, Eusebius notes that Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150-215AD) provided a brief commentary on all the canonical books, including the letter of Jude and the other Catholic Epistles (Ecclesiastical History, VI 14, 5). This document itself has been lost, but a Latin translation of Clement’s commentary on 1 Peter, 1 and 2 John, and Jude has been preserved. This ancient Bible commentary from Egypt most probably already gave attention to the Catholic Epistles.

Tentative Conclusions←⤒🔗

From the foregoing, three tentative conclusions may be drawn. First, the expression ‘Catholic Epistles’ has been the term for a specific group of seven letters, which originated in the apostolic period. Second, there was some debate regarding the authenticity of at least two of them; apparently, there was some doubt concerning their authorship. In the case of James and Jude, as mentioned by Eusebius, this is likely because the author does not identify himself as an apostle. However, with regard to James, there was also a larger problem: a number of apocryphal writings were in circulation, purportedly under his name (The Infancy Gospel of James, the Apocryphon of James, and the First and Second Revelations of James). Third: in spite of the margin of uncertainty concerning their authorship, both of these letters were freely used in the churches, that is to say: just as all the other authoritative writings, they were read aloud throughout the world as accepted parts of the church liturgy.

There is, therefore, every reason for a re-evaluation of this collection of letters, the more so, since it enables us – in the words of the 20th-century New Testament scholar J. de Zwaan of Leiden – to better distinguish the range of voices that speak to us from the New Testament. Schlosser believes that we are dealing with a homogenous corpus, while Wall has demonstrated that the seven Catholic Epistles are not just a random collection, but as to their content form a coherent whole.15 Be that as it may, the collection of seven Catholic Epistles forms a precious possession of faith for the world-wide church.

What exactly does the name ‘Catholic Epistles’ signify? In what respect are they general? This is commonly understood to mean ‘generally recognized’ or ‘generally distributed’. At an early date already, there would have been the realization that these letters were not specifically intended for one church, but were meant for the worldwide church as a whole. This explanation, however, is not altogether convincing.

To begin with, the development of the canon implies that all of the New Testament writings are of importance for the whole of the Christian Church; the letters of Paul, for example, were also read in other churches. In addition, some of these Catholic Epistles really do have specific addressees, as is evident from their prefaces. James is written to the twelve tribes in the diaspora, 1 Peter to Christians in a number of specifically designated regions in Asia Minor, 2 John to a specific but not explicitly identified sister-church, and 3 John to the ‘beloved brother Gaius’, the leader of a specific church.

Catholicity←⤒🔗

It is worth considering whether the catholicity of the letters does not have more to do with the catholicity of Jerusalem. All their authors, after all, had come from the mother church in the holy city. As such, we could say that these letters document the catholic mission movement that went out from Jerusalem. James, the leader of the church in Jerusalem, was the brother of the Lord; the same was true of his younger sibling Jude; Peter and John (assuming that John is ‘the elder’ identified as the author of two of the Johannine letters) were close companions, who played an important role in the early days of the church. It is through these ‘catholic’ men, apostles and brothers of the Lord, fully involved in the proclamation of the Gospel that proceeded from Jerusalem, that the close connection between the book of Acts and these seven Catholic Epistles can be easily explained as well. The chief characters in Acts developed as authors of the church. Something else must be taken into account: In Galatians 2:9, in connection with his earlier visit to Jerusalem, Paul describes James, Cephas (Peter) and John as ‘pillars of the church’. James comes first. He was not an apostle, but he was the leader of the church in Jerusalem. It is perhaps no coincidence that Paul lists their names in just the same order in which six of the seven Catholic Epistles are passed on to us in the canon. They came from the three pillars of Jerusalem, the three most prominent members of the mother church, who, for just that reason, were regarded as authority figures throughout the Christian world. A seventh document, a short letter from Jude, has been added to the other six. This is presumably because the author introduces himself as the brother of James, and also because he makes use of material from Peter’s second letter.16

Thus, seven Catholic Epistles were sent into the world: written material from the circle of the pillars of Jerusalem; documentation of the ecumenical movement that proceeded from the mother church in Jerusalem. What follows is a brief description of each of the seven letters.

The diaspora letter of James, the brother of the Lord. As we observed already, this letter is addressed to refugees from the Jewish-Christian church of Jerusalem. The ‘twelve tribes’ mentioned in the address clearly do not refer to a Christian diaspora, but to the tribal relationships of Israel, in which the Christian believers had their roots. James follows a Jerusalem tradition of letters, full of instructions and advices, aimed at Jews living in the diaspora. He acts as a teacher of wisdom, in the style of Jesus himself. It is likely that this letter of exhortation was written before the convent in Jerusalem, and before the mission to the Gentiles began.

Peter’s circular letter from Babylon. Peter, having fled Jerusalem, had gone to ‘another place’ (Acts 12:17). This place was not Rome, as is so often thought. This idea is based on the book of Revelation, where Rome is compared with Babylon. However, the Babylon referred to at the end of 1 Peter denotes an actual place. To ensure that Herod could not find him, the apostle had to leave the territory of the Roman Empire; hence, he went to Babylon in Mesopotamia, where there was a Jewish community. From there he writes to Gentile Christians in Asia Minor, living in all regions of the address, arranged in an imaginary circle. Silas delivered this letter, and provided further elucidation.

The testament of Simon Peter. As he felt the end of his life approaching, Peter wrote a second letter to the same readers as the first one, a spiritual last will and testament. He warns against false teachers, who will try to turn back the clock on their Christian identity. Let no-one think that God will leave this evil unpunished. In the same manner as the world was once engulfed in a deluge of water, so the Almighty will carry out his last judgement with all-consuming fire. Isaiah’s ancient promise will then be fulfilled: “we are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth, the home of righteousness.” (2 Peter 3:13) 5 and 6. Church mail from the eldest witness (John). The author of the second and third letters of John calls himself ‘the elder’. He is almost certainly the apostle John, the longest-surviving witness to the resurrection (John 21:23). It is likely that the first letter was intended to commit to writing his apostolic witness to his own congregation. From his second and third letters, it is clear that John had intentions to visit a sister church; to ensure that he is welcome when he comes, he informs both the congregation (2 John) and its leader, Gaius (3 John), of his impending arrival. The testament of Jude, the brother of James. Actually, Jude’s letter is one long and varied list of examples from Israel’s history (from both the Old Testament and Jewish tradition), providing documentary evidence that the wicked will not avoid their punishment: their sentence has long ago been determined and written down. Even though Jude’s letter bears strong resemblance to 2 Peter 2, his readers are probably Jewish (as opposed to Gentile) Christians. Besides, Jude was not one of the apostles. He points to them, and identifies himself as James’ brother. James was put to death in 62AD; this may be his spiritual testament, written on his behalf by his younger brother Jude.

The Jerusalem Perspective of Hebrews and Revelation←⤒🔗

There are good reasons to suppose that the letter to the Hebrews was written to Jewish Christians, who had come from Jerusalem. Eusebius recounts that they were able to flee from Jerusalem just before the Roman conquest, and went to Pella, a Hellenic city across the Jordan, about one hundred kilometres to the northeast.17 The letter to the Hebrews is intended to encourage these believers: we have no lasting city here, so do not become fixated on the earthly Jerusalem; instead, fix your eyes on the Jerusalem above, the city of the future (Hebrews 13:14). Our High Priest has entered the heavenly sanctuary, and he has brought about an eternal reconciliation. Hence, the cultic sacrifices of the present Jerusalem have come to an end. The letter to the Hebrews is a ‘word of encouragement’ (logos paraklèseoos; Hebrews 4:36), that builds stylistically on a form of preaching that was common in the synagogues. An ancient tradition suggests that Hebrews’ anonymous author may have been Barnabas, and he was certainly no stranger in Jerusalem. The apostles had given him the surname ‘son of encouragement’ (huios paraklèseoos; Acts 4:36).

The significance of the book of Revelation for the Jerusalem perspective becomes especially clear near its end: John, exiled to the island of Patmos, sees a new Jerusalem coming down out of heaven. And from the throne in heaven a voice resounds: “I am making everything new!” (Revelation 21:5). For God is making his dwelling place – not just with the people of Israel, as it was before, but ‘with men’ (meta toon anthroopoon; ch 21:3). When the new city is measured, she is revealed to be as wide as the whole world. Its gates are invitingly open to all directions of the compass, and those who would be its inhabitants stream towards it. But not everyone is welcome in the city (ch 21:8, 27; 22:15) only those who honour and serve God. In the cityscape of the future, the proud temple of the past is no longer there: God himself has become the temple of the new Jerusalem, together with the Lamb. The paradise curse has been lifted (ch 22:3) so that there is now ample space for the blessing of God. “Blessed are those who wash their robes, that they may have the right to the tree of life and may go through the gates of the city” (ch 22:14). Jerusalem truly does become a holy world metropolis!

Add new comment