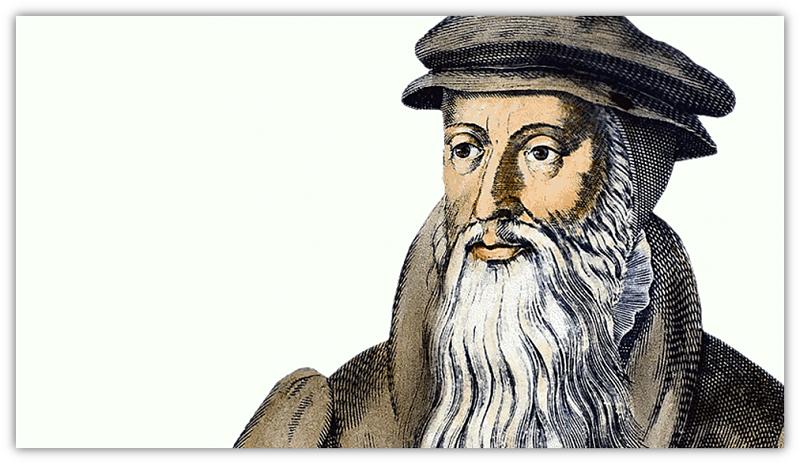

John Knox: The Iron Man of Reform in Scotland

John Knox: The Iron Man of Reform in Scotland

The reform carried out by Luther and Calvin came at a much later date to Scotland than to Germany and Switzerland. Although Scotland lacked early leaders as in Germany and Switzerland, it had a powerful leader in the person of John Knox. A historian wrote: "John Knox provoked rulers, incited riots, and inspired a reformation in Scotland." According to an English ambassador, "He put more life into his hearers from the pulpit in an hour than the blast of six hundred trumpets."

Early Life⤒🔗

John Knox is thought to have been born around 1505 in Haddington, a small town south of Edinburgh. His parents were lower to middle class; his father a craftsmen or merchant. Although of humble origins, he received a good education, mastering Latin and attending the University of Glasgow by 1529. He studied theology and was ordained in April 1536. This did not lead to a parish appointment since there was an excess of priests in Scotland. Undoubtedly, we can distinguish the hand of God here, for Knox became a public notary at Haddington and tutor to sons of lower ranking nobility instead of a practicing Roman Catholic priest. It would be some ten to fifteen years later before Knox became a zealous advocate for religious reform.

Background Information←⤒🔗

At the dawn of the sixteenth century, Scotland was a poor and backward country experiencing mediaeval social conditions. The universities of Glasgow, St. Andrews and Aberdeen were inferior and weak compared to those of continental Europe. During the first half of the sixteenth century Scottish political history was dominated by the fear of being annexed by England on the one hand and being conquered by France on the other. It seems that this social and political climate caused the Reformation in Scotland to progress at a very slow pace. John Knox did not become vigorously involved in the movement for reform until he was well over 40 years of age.

At the turn of the century, papal authority dominated Scotland and Archbishop James Beaton was its primate until 1539. However, through constant sea traffic between Scotland and Europe, Lutheran literature was smuggled into the country and the seaport town of Dundee became an early centre of Protestant activity. The church authorities became alarmed at the advance of "heresy" and tried to suppress it. In 1528 Scotland had its first Protestant martyr in the person of Patrick Hamilton who had been to continental Europe and had studied at Wittenburg, Germany. Hamilton was arrested, imprisoned at St. Andrew's castle and brought to trial for spreading heresies. He died a slow and painful death at the stake. His death made a great impression upon many people and it has been said that "his reek infected all it blew upon'' since many of the people in and around Edinburgh became sympathetic to the cause of reform.

Knox Preaches the Gospel←⤒🔗

Eighteen years passed with some less notable men also experiencing martyrdom, until the godly George Wishart, who had become more and more convinced of the need for reform while in Germany and Switzerland, began to preach the Gospel to his fellow countrymen, at times in the open air. Knox joined Wishart's band and found himself in agreement with his preaching and call for reform. However, the new Archbishop of St. Andrews, David Beaton, arrested Wishart and brought him to trial in January of 1546 and had him executed and burned at the stake. For Knox, Wishart was a great hero, "a man of such graces as before him were never heard within this realm, yea, and are rare to be found yet in any man."

Wishart's preaching and martyrdom influenced Knox, so that when a group of nobles took matters in their own hands by assassinating Beaton, he approved on the principle that God often allows evil men to mediate punishment.

When Wishart died, the martyr's followers received Knox as his successor. This marked the beginning of widespread Protestantism in Scotland. The people demanded that Knox become their minister. While considering the call from St. Andrews, Knox is said to have attended a service in a parish church where Knox, not being able to constrain himself, stood up from his pew and declared that the Roman Church was no bride of Christ but a harlot! The congregation demanded that he justify his remark in a sermon on the following Sunday, which he did; and so the public career of one of the most powerful preachers of the Reformation era was launched. Concerning Knox's preaching it was said that he sawed the branches off the papacy and he put the axe to the trunk of the tree. In the pulpit, Knox was apparently so energetic that he seemed to pound it to pieces and to fly out of it.

Knox is Equipped for his Great Task←⤒🔗

By the year 1546 Knox was firmly convinced and committed to reformation.

Yet the Lord did not use His servant to effect a lasting reformation until nearly fifteen years later. Very soon, after beginning to minister at St. Andrews, a French fleet laid siege to St. Andrews Castle and when it capitulated in July 1547, many were taken prisoners, including Knox. He was required to work as a galley slave on a sailing ship for 19 months, all the time being pressured to renounce Protestantism. However, under the government of King Edward VI of England, many prisoners were given their liberty, including Knox.

For five years Knox laboured in England while Scotland was groaning under the dominance of Rome. It was during this time that he met thoroughly Reformed preachers such as Latimer, Ridley, Hooper and Miles Coverdale, who had been influenced by Calvin in Geneva. While in England, Knox assisted Archbishop Cranmer in formulating the Forty-Two Articles, a Protestant creed adopted by the Church of England. In the position as a chaplain to the king, Knox also contributed to the preparation of the Edwardian Second Book of Common Prayer of 1552.

At this time his fiery nature became evident and he was propelled to the front lines of reform. Knox sternly opposed kneeling to receive Holy Communion, which had been required in the First Book of Common Prayer. Knox was also invited to become Bishop of Rochester and later vicar of the influential All Hallows Church in London, but he refused both positions.

The following year, when Edward VI died and Mary Tudor began her reign, this political development interrupted Knox's career in England. By 1554 Knox had fled to France with a host of other leading Protestants and made his way to Geneva, where he met John Calvin for the first time. Knox is said to have exclaimed: "This is the most perfect school of Christ that ever was upon the earth since the days of the Apostles. In other places I confess Christ to be truly preached, but manners and religion so truly performed, I have not yet seen in any other place." Knox spent four happy years in Geneva until he became pastor to an English-speaking church in Frankfurt.

When Knox ministered in Frankfurt, he was confronted with the question of what liturgy to use. He had become unhappy with the Edwardian Common Book of Prayer to which he had also contributed, but neither was he satisfied with Calvin's Genevan Order of Service. When a group of exiles who would later become leaders in the Elizabethan Church in England, arrived in 1555, Knox and some of his supporters drew up a new order of service. To the chagrin of its pastor, the majority of his church rejected this new order of worship. However it would later become more significant than Knox could have imagined. In 1560, only five years later, it became the Book of Common Order, the official worship book of the Church of Scotland.

Soon the city officials expelled Knox and he returned to Geneva where he preached to a small congregation of English exiles. During this time he had a hand in the publication of the Genevan Bible. This Bible would be used in both Scotland and England well into the 17th century.

Knox Returns to Scotland←⤒🔗

While an exile in Geneva, Knox made a visit to his native land, even though there was a price on his head. He was hidden by the nobles and went from place to place to proclaim the Word. Very remarkably, a true hunger for the Word had been born in the hearts of many in Scotland. The Lord had been working in a mysterious way through the power of the Holy Spirit. Clandestine Protestant congregations were forming in Edinburgh, Dundee, St. Andrews, Brechin, Perth, and elsewhere. By 1557 these gatherings, which could be compared to house congregations, became Reformed congregations.

Leading members of the nobility drew up a covenant to promote and establish the most blessed Word of God and His Congregation in Scotland, renounced Catholicism and vowed to make Protestantism the official religion of the land. At their insistence Knox had returned to Scotland for nine months, preaching extensively. During this time he was summoned to Edinburgh to face legal proceedings. When regent Mary of Guise cancelled the summons, probably to save face, Knox sent her a letter, thanking her for her clemency but also requesting complete toleration for Protestants. This caused her to become less conciliatory and as a result Knox left for Geneva at which time he also published some of his most controversial tracts concerning the impropriety of women being placed in positions of authority. Mary was so angry that she burned an effigy of Knox.

By 1559 Knox returned to Scotland again. This time he stayed and preached fearlessly and with great eloquence against Catholic idolatry. His preaching was like a spark in a keg of gunpowder and resulted in altars being demolished, images being smashed and monastic houses being destroyed. Knox wrote: "The places of idolatry were made level with the ground, the monuments of idolatry consumed with fire, and priests were commanded under pain of death to desist from their blasphemous mass."

When Mary of Guise called on French forces to put down the rebellion, the Protestant nobility promptly occupied some of the major cities. In Edinburgh, the citizens elected Knox to be their minister and he used the pulpit to exhort and inspire his Protestant listeners to remain true to the cause God called them. He knew, however, that without English intervention they would not be able to resist the French reinforcements Mary had sent for. Because of his opinion concerning women in political office, Knox was also very unpopular with Queen Elizabeth I. The nobility, however, was successful in drawing up a treaty with the English monarch in February 1560. Called the Treaty of Berwick, England promised to provide military assistance to counter Mary of Guise and the French troops. Obviously, this was also in the interests of England, since it had become decidedly Protestant. Four months later both the French and English agreed to leave Scottish soil and thus the future of the Reformation in Scotland was assured.

The Reformation is Firmly Established in Scotland←⤒🔗

Within a month of the peace treaty, the Scottish Parliament met and Knox preached at a thanksgiving service to a most distinguished congregation in St. Giles' cathedral in Edinburgh. The Parliament called upon Knox and five colleagues to write a Confession of Faith, which remained the main statement of faith for the churches of Scotland until the Westminster divines met in 1647.

The same theologians also drew up A First Book of Discipline, which was submitted to the General Assembly of the Reformed Churches of Scotland at the first meeting of the new national church. It attempted to apply the system worked out by Calvin for his church in Geneva and thus was a rudimentary form of Presbyterianism. This Book thus set forth rules and regulations by which the local church as well as groupings of churches were to be governed.

Knox, therefore, can be called the pioneer in developing a Presbyterian form of church government. In each parish or local church, the minister, together with the elders, were chosen from the members of the church, which constituted a session. Meetings, where churches of certain areas were represented by delegated ministers, were called presbyteries. Meetings at which larger groups of churches were represented by delegated ministers and elders were called synods. Beside these there were also meetings in which all the churches of the country were represented by delegated ministers and elders. These were the general assemblies.

Another notable achievement of Scotland's reformer was the implementation of a Book of Common Order, which was based to a great extent upon the form of public worship used by the English refugees in Geneva. The order of worship consisted of prayer, reading of the Scriptures, the sermon, congregational singing and the taking up of the offering, very similar to the worship services patterned after Calvin as in our denomination.

Some Conclusions←⤒🔗

John Knox, the thundering Scotsman, as he is sometimes nicknamed, was mightily used by the Lord to bring about a lasting reformation in Scotland. His ministerial labours had been stormy, but by the grace of God he was a man of dauntless courage. In genius, learning, and ideas he may have been inferior to Luther and Calvin, but in boldness, strength, and character he was fully their equal. His pious fear of God made him a fearless man. Next to Calvin, he is the chief founder of Presbyterian church polity, which has proved its vitality and efficiency for more than three centuries.

John Knox died on November 24, 1572 while preaching to his people at St. Giles where he had been physically carried into the pulpit. He died, wearied of life and longing for heaven at the probable age of 67, peacefully without a struggle. Clergy, nobles and the people alike lamented his death. The last words of this fiery man were: "I never hated people, although I had to bring the judgment of God to them. I only hated their sins, and I tried with all my strength to win their souls for Christ." The epitaph on his grave was: "Here lies a man who never feared the face of a man, John Knox, the unyielding reformer of Scotland".

Add new comment