Developments in Redemptive-Historical Preaching

Developments in Redemptive-Historical Preaching

What is Redemptive-Historical Preaching?⤒🔗

I am conscious of the fact that the redemptive-historical method is one which is increasingly falling out of favour today, and that we have a younger generation that hardly realizes what it is about. This is very unfortunate, because it means that there is a larger group of people in the pew who have little idea of what preachers are trying to do with the so-called historical texts of Scripture. And if the method is not understood, the sermons will be that much more ineffective for the listener. People will be more apt to lose the train of thought if they have no idea about the principles operative in the craft of building the sermon.

Allow me then to review briefly what the essential principles of this method are all about. I concentrate on the development as spearheaded by K. Schilder, and expanded by B. Holwerda and M.B. Van 't Veer.

The Context←⤒🔗

The central rule of this method is that a historical text must be preached in the framework of its historical context. This method is generally contrasted with the exemplaric method, in which Old Testament events or personalities were taken out of their contexts and used as examples for moral behaviour today. It is also contrasted with the method of artificial typology, which sees in every Old Testament figure a type of Christ. Thus, for example, as Potiphar left everything to Joseph's charge, so we are to leave everything to the charge of Jesus, his great antitype. In all these methods, the figure or event is taken out of its context, and then made to serve as a model for the believer today.

Redemptive-historical preaching leaves the characters of a narrative in their context. Its fundamental principle is that the narratives of Scripture record the mighty acts of God in His dealings with His people and with the nations of the world. These are acts of salvation for His people, and acts of judgment for all who oppose His salvation work for His people. In the progression of the narratives we meet the unfolding drama of the way of God with His covenant people.

The Purpose←⤒🔗

With any passage in the Old Testament or the gospels, the fundamental purpose or thrust of the account must be uncovered. This must always be seen in relation to Christ. In other words, the text must be placed not only in its immediate context, but also in the wider context of the whole history of redemption. The key thought in the old covenant is: the struggle between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent, Genesis 3:15. This struggle has a universal character and governs all of redemptive history. Essentially history is determined by three all-pervasive court cases: the fall into sin, the judgment on the cross, and the final judgment at the last day.

The Events←⤒🔗

Redemptive-historical preaching stresses the requirement of preaching the magnalia dei, the mighty acts of God. M.B. Van 't Veer in particular stressed this point in his article on this method.1 We cannot use the Old Testament as one big allegory, or as a book of signs or metaphors. We are to see it as the unfolding of the revelation of salvation history of God. The history of revelation is to be distinguished from the history of salvation. Yet in both cases we are dealing with factual material, and actual events. Thus, one must construct a sermon with the time line in mind. The overarching question is: how does God come, through the events described in the text, to the fulfilment of His work in Jesus Christ? The preacher need not leave his text to come to Christ, but should focus on what God is doing in the Son at any given specific historical point.

Trimp's “Resumption”←⤒🔗

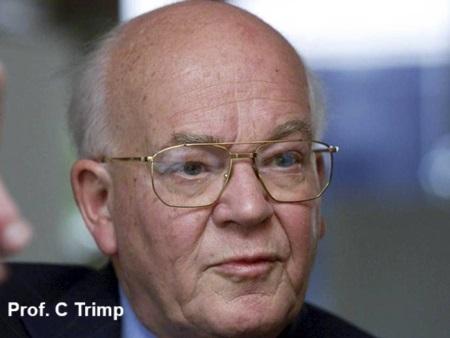

In the winter of 1986 Prof. Trimp gave a series of lectures on redemptive-historical preaching. These lectures attracted a good number of students, and I remember that they were the subject of much discussion at the time. The results of these lectures were published in a booklet called: Salvation History and Preaching. The Resumption of an Incomplete Discussion.2 In the title, Trimp alludes to the fact that the discussion between the proponents of the exemplaric method of preaching and the redemptive-historical method was never really completed. As S. Greijdanus pointed out, the problems surrounding the conflict on baptism and regeneration took the center stage, and after the Liberation the proponents of the different methods found themselves in different ecclesiastical camps as well.3

What are some of the salient features of the contribution of Prof. Trimp on this method? Let us look at a brief survey of the points he raises.

The Scriptures as Narrative←⤒🔗

One of the elements that received little or no attention among the first proponents of the redemptive-historical method is the narrative character of Scripture. This is understandable, since it was only in more recent times that hermeneutics and biblical studies have given attention to this aspect of the Scriptures. In the light of this new research, Trimp suggests that all the emphasis of the redemptive-historical method on the linear or historical line to Christ is overexposed. The biblical accounts are primarily to be seen as multi-layered dioramic pictures, which look at events from various points of view. Hence the specific dimension of narrative must be reflected in the sermon. The preacher must ask questions like: why was this written in this particular way? What are the key elements in the content and structure of the account? He must also pay attention to key structural features of narrative and their significance in comparison with parallel or related narratives.4

Fellowship←⤒🔗

The overexposure on the idea of linear progression led in Prof. Trimp's view to an underexposure of the idea of fellowship in the redemptive-historical school. His point is that the progression serves the fellowship, rather than the other way around! For example, in a sermon on Abraham, often all emphasis fell on Abraham's role with respect to the coming of Christ. But then the concept of friendship with respect to God's relationship with Abraham fell into the background. Yet these are elements which must be highlighted, because they show the style of the God of the covenant in His relationship with His people.

Example←⤒🔗

Trimp also disagrees with the complete rejection of the idea of example which characterized the approach of the early redemptive-historical school. Prof. B. Holwerda maintained that the term “exemplum” had no historical connotations whatever.5 Trimp maintains that the historical dimension is not necessarily lacking in this term. In opposition to all “psychologizing” on Old Testament figures, Holwerda maintained a sharp distinction between the ordo salutis (order of salvation) and the historia salutis (history of salvation). In other words, one ought not to use all kinds of Old Testament figures to describe the Spirit's way of working faith and regeneration in the hearts of God's children. Here Trimp prefers not to apply such a sharp distinction, and is willing to allow for some discussion of the Spirit's work in the believers of the old covenant, as long as the historical context is respected.

Sound and Echo←⤒🔗

In 1989, Dr. Trimp published the book Sound and Echo. Through Preaching to Faith Experience, in which he continued on the course he established in 1987.6 It became clear that the element of “omgang” or “fellowship” began to receive increasing attention in his work. In this book, Trimp reaches back into the history of preaching in the Dutch churches to analyze the development of the relation between preaching and faith. He notes that during the time of the Secession two kinds of sermons were distinguished: subjective and objective. The former kind was praised, the latter frowned upon. The Liberation of 1944 was essentially a confrontation with the tradition of the Secession and the so-called Second Reformation in Holland (“Nadere Reformatie”). In opposition to the subjectivism dominant in this period, the Liberation led to a new emphasis on God's covenant and its promises in the preaching. In His covenant Word, God opens His heart to us. Trimp says that the true covenantal preaching liberates our “feeling life” so that it becomes fully involved in the service of God. The capacity of our feeling life will always remain imperfect in this life. Yet, experience cannot be ruled out as a dimension of faith. Experience is a daughter of faith, the result of an obedient listening to Scripture.

In his historical study, Trimp shows how the Reformers, in particular Calvin and Luther, saw the preaching of the Word of God as the presence and active working of the living God. The good news of the Scriptures must be laid on the hearts of the congregation. The period of Reformed scholasticism saw the emphasis shift away from the living covenant relationship to a mechanical model. Instead of representing a living voice, God's revelation becomes a dead letter, a cold, methodical set of concepts. Faith becomes one of the virtues that human nature must acquire. Preaching becomes a scholastic treatise, a summary of mechanical steps necessary to acquiring the state of grace.

The period of the second reformation (“Nadere Reformatie”) makes a swing to the opposite extreme, and centralizes the experiential aspect in the preaching. This led to a style of preaching called: differentialized preaching (“onderscheidelijke prediking”). Distinctions were made in the congregation between the doubting, the saved, the mature, the unrepentant, and so on. Inordinate attention was given to the actual experience of the characteristics of conversion in one's soul. Ultimately, the preaching acquired a strong experiential and man-centered focus.

Trimp then examines the character of normative, covenantal preaching. He begins with an analysis of the Reformers' use of the word “promise.” He states that this term was not taken as a pledge that God will do something in the future, but as God's speaking in the present. This is how it ought to be understood today as well.7 God proclaims a good tiding by which we are all acquitted today through faith. God gives His grace not in substantial categories (Rome), but in His word of power. Trimp then disputes the thesis that true covenantal preaching posits an exact balance between promise and demand in the covenant. If one would follow such an approach, he enters into the waters of a cold objectivism. Trimp intimates that some of the preaching (and/or writing) in the Liberated churches may have leaned in this direction. Promise and demand is presented as a factual “balance sheet,” with the congregation left to decide for themselves where they fit in on the sheet. For Trimp, the demand in the covenant can only be fulfilled in the way of appropriation of the promise. In other words, the demand is part of the promise. The promise must then be preached with this dimension of grace in mind.

All this has led Dr. Trimp to a deeper reflection on the relationship between preaching and faith. Preaching is the vehicle by which the eternal things are applied to our lives. We cannot but respond to the preaching. It quickens our resistance, but also activates our faith, and believing acceptance. It drives us to overcome the resistance to the Word which lives in our sinful hearts, and leads us to the “echo” – the communal, unified song of praise and thanksgiving to the redemptive work of God.8

An Assessment←⤒🔗

The above sketch is only a brief survey of Trimp's position. Yet I hope it is clear that in all this Trimp has charted a new course, and in this course he has followed a very careful, but also deliberate strategy. He wants to recover the emotive element in the homiletical field of vision, without falling into subjectivism. At the same time, he wants to use this specifically scientific aim in service of the more practical aim of reevaluating and reassessing the relationship with the Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken. What should one say about this development?

In this sense I do not think that Trimp has succeeded in “resuming” an incomplete discussion. Rather, he has started a new one. In this round of discussions his partners are not people from the synodical camp, but from the “Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken.” This only stands to reason, since I think that the aim to restart an older discussion was not sufficiently cognizant of the historical time gap between the forties, and the climate today. Representatives of the exemplaric school as they existed in the forties and fifties are hard to find in the synodical churches today. There doctrinal deterioration has led to a new radicalism in the preaching which is totally estranged from the debate of the thirties and forties.

With respect to the direction taken, I think Prof. Trimp gives us some essential contributions to the view of preaching which can assist us in improving its practice today. Specifically his concern not to ignore the element of the people's participation in the salvation acts of God is a new dimension which certainly was not always sufficiently considered by all the first proponents of the redemptive-historical method. On the other hand, it should be stressed that Holwerda warned against the introduction of false dilemmas, including a false dilemma between subjective and objective preaching, as well as between the Word and the Spirit.9 Thus, while there may have been some one-sided emphases in the redemptive-historical method as first propounded, there was not a deliberate failure to include the aspect of faith and its experience in the approach that was taken.

I believe that we must adhere to the fundamental principles of the redemptive-historical method as outlined by its first proponents. Dr. M.B. Van 't Veer said that there could be no synthesis between the two approaches, and I believe that he was right. This does not mean that we should neglect the role of example in the preaching. But its role will always be qualified by the essential redemptive-historical approach to the text.

What about the recovery of the emotive element in the preaching? This is partly a function of the gifts and character of the preacher. Yet, the Word must be laid on the hearts of the congregation! The preacher must do his utmost to ensure that the Word strikes to the heart of the listeners. Therefore the emotive element in any given Old Testament narrative can serve as a comparative or analogical point of reference to deal with the same aspects of the relationship between God and the believer today. But then historical differences must always be duly accounted for. I see this as most far-reaching development in Trimp, which certainly asks for further reflection and consideration.

Particular caution must be exercised with respect to passing moral judgments on Old Testament figures. Often the sacred writer himself makes a judgment, so providing clear lines for the preacher. But in many cases, the question as to whether a specific course of action was right or wrong is not easy to determine, and even if it is discernable, it is not the central idea in the passage. A more important theme to my mind is that despite the many weaknesses and shortcomings in the actions of the saints, the LORD God still uses these actions to accomplish His salvation purpose.

The proper approach to preaching historical texts provides a continual challenge to the preacher. We certainly can be grateful for the unique contribution of Prof. Trimp to this important topic. Our hope is that the contribution he has made will also serve to enhance this method of preaching for years to come. It is also to be hoped that the method of redemptive-historical preaching is continually revised and developed to improve the preaching on the historical passages of Holy Scripture.

What about the discussion with the “Christelijke Gereformeerde Kerken”? This is indeed a positive note in Trimp's work. This discussion is most necessary! We all need to take a closer look at the true character of the “experiential moment” in the preaching, without falling into the waters of a man-centered subjectivism! In the Netherlands there are certainly some positive tokens of real headway being made in this area. That is an example for us to follow in discussions with the Free Reformed Churches!

All this points to the fact that we are far from finished in the task of reflecting upon and improving the art of preaching – in general, and on Old Testament historical passages in particular. May the Lord grant that preachers apply themselves to this task with ever new zeal and vigour, that the Scriptures may be fully exploited according to their essential purpose – for proclamation of God's mighty deeds!

Add new comment