The Sermon: What May we Expect?

The Sermon: What May we Expect?

The weekly sermon remains a favourite topic of conversation among church members. And rightly so because the preaching has indeed a most central place. You might even say that it is the source, the fountain from which the church draws life.

However, often these conversations leave us dissatisfied; rarely do we feel spiritually uplifted by them. There is an important question which precedes and therefore influences all these conversations: What may we expect from the sermon?

Our discussions about the sermon will undoubtedly be of greater value when we have considered this question in a responsible manner. This and following articles were written to help in these considerations.

So Many Men…⤒🔗

Often the discussion of the sermon bogs down because of the varying expectations of the individual listeners. Some consider the sermon satisfactory only if something has been learned from it. Others desire a word for their heart, rather than an Instructional sermon. The one church member expects a thorough exegesis of the text and suggests, "I will decide for myself what application I will make for my daily life." Others hope for a message which has a direct application for his or her own situation. Many people appreciate a lively presentation, while others might consider the presentation itself of little importance. Some like the sermon to be an intellectually demanding, scholarly discourse, while others prefer sermons which address the congregation in a more popular fashion.

Indeed, there are many different ways in which listeners may approach the sermon. Of course, no one will be surprised to hear that no minister will even try to honour all these wishes. However, as long as such expectations determine the way in which we listen to the sermon, its blessings can be greatly diminished. That becomes obvious when in a discussion about the sermon the opinions badly clash.

It is the express purpose of the sermon to bring together all these different people so they will find each other under the ministration of the Word which speaks to all of them, but you will not find each other when there are sharp divisions of opinion on what may be expected from a sermon. This applies most certainly to the sermon discussion in the consistory meeting.

The Consistory and the Sermon←⤒🔗

Sermon discussions do belong on the agenda of the consistory. Although only the minister has the task to preach the Word, he is not the only one who is responsible for faithful preaching! The supervision of the preaching is the special task of the elders. After all, they are, together with the minister, the shepherds of the flock. Therefore it is their responsibility to ensure that the voice of The Shepherd is heard in the sermons. We can prevent the preaching from becoming the business of one man only by taking this responsibility seriously.

It is proper that this responsibility receives much attention during the period of the calling of a minister. But this responsibility must also function after the arrival of the minister. Based on their experience within the congregation, the elders will be able to indicate to the minister what the needs of the congregation are. And further, during the regular family visits they will be able to discern whether the congregation can and indeed does work with the sermons.

A wise minister will not be deaf to the comments of his fellow office-bearers. A fruitful dialogue between the minister and the elders can be of great benefit to the sermons.

Yet, many a consistory seems to have problems with the sermon discussions, as is evident from the regular complaints I hear. This is not because the elders do not dare to discuss the work of the minister. The time when the minister was regarded with awe and when no one would dare criticize him (after all, he had studied for it!) is far behind us. Those who take their responsibility seriously should be able to overcome their hesitancy (with the help of the minister!).

But the actual sermon discussions during consistory meetings show that the brothers have widely divergent expectations. If every one considers the sermon on the basis of his own point of view, a sermon discussion will bog down and the minister is left to help himself. Undoubtedly, there will be ministers who do not mind such a situation, but the congregation will suffer. If it is true that the preaching is such an important life-giving fountain, then the congregation may expect that the consistory will supervise the preaching with the utmost care. Therefore, the question, what may we expect from the sermon? Is not only of great importance to all church members, but also to each consistory member.

Sermon Evaluation←⤒🔗

In the meantime, someone might interject with the question; Do we still do justice to the nature of the preaching in this way? After all, we are here concerned with the Word of God which is ministered on His authority. Should everyone be allowed to voice his opinion? Should everyone in the church become a sermon critic? What, then, is left of listening to the gospel out of thirst for the gospel of salvation?

These are important questions. The kernel of the preaching concerns the question whether we are truly willing to listen to what the LORD has to say. If that does not come first, there is no point in even discussing the sermon at all. It is not the purpose of a sermon either to allow us to settle down in thorough judgment. Listening to a sermon for critical analysis only places us outside the gospel.

The point is, we must deal with the sermon in a fruitful and constructive way. Therefore we must think about what we may rightly expect and not expect from a sermon.

Checklist←⤒🔗

Someone once asked me, "Can't you develop a kind of checklist for the essential points of a good sermon?" This seems an attractive idea. Checklists are useful when they function as a guideline which you can use to orient yourself quickly, and to enable you to identify important aspects.

To me, however, there is too much of a critical element implied in this suggestion. A checklist often functions in a situation of inspection and examination. With the help of such a list you run past the main points and you check whether all is well. I feel that this is inappropriate in the church. As a member of the church (and consistory) you are not called to give the minister a grade for his sermon. The main purpose of the preaching is to give yourself captive to the LORD. Only with such an attitude can we speak usefully about the question whether the sermon measured up to what we rightly may expect from it. Such an attitude does not permit us to listen as inspectors who will quickly and efficiently check whether all things are in good order.

On the other hand, the request for a checklist does have a positive element. We recognize that the preaching must measure up to certain norms, don't we? It is important that we are aware of those norms, and that we are able to use them when speaking with each other about the sermons. At this point a comparison with a method advocated for the family visit may be helpful. Rev. C. Vonk wrote a book with the title, Family Visit According to God's commandments.1 He pleads for the use of the Ten Commandments as a guide for the family visitation. The elders should consider whether a particular family serves the LORD according to the first commandment etc. This method has been strongly criticized. I once even heard the remark; I would feel like a meter-reader! That danger does exist. A strict adherence to the order of the Ten Commandments might make the family visit rather unpleasantly formalistic. The impression might be made that the elders have come to check out the situation, while the actual, everyday concerns of the members of the congregation may be left unmentioned.

But it is equally possible to view this method from a different angle. Consider that the Ten Commandments are the rule for our life, given by God Himself, by which our lives take shape before Him. Therefore the use of such a rule as a guide in the preparation for the family visitation as well as for the visit itself can be very helpful indeed. The point is not to ensure that all aspects will be covered. Elders should listen a great deal, and if they are called to speak they will have to speak about much more than is mentioned in the Ten Commandments. However, the rule which we have received from God Himself can be a powerful tool in the work of the office-bearers.

In the same way it is possible to formulate a number of norms, biblical criteria which describe what we may expect from a sermon. A careful use of these norms will be of much help when listening to and speaking about the sermon, without the risk of becoming an inspector who checks off the items on a list to determine whether the minister has gained a satisfactory grade. Based on these considerations I have tried to provide a brief formulation of what we rightly may expect from a sermon.

What May We Expect from a Sermon?←⤒🔗

Of course, it is not my intention to be complete and all-inclusive. My purpose is to indicate major criteria for a sermon to help shape the expectation of the listener. In addition, the norms which I will try to formulate are meant to be norms for the preaching as a whole. It would not be fair to demand that all of them should be present in each sermon. Obviously, certain aspects will be emphasized more in one sermon than in another. Therefore the following list should be helpful to shape our expectations about sermons over the long(er) term.

In formulating these criteria I have considered especially the nature, the content, and the form of the sermon.

In summary: we may expect a sermon to be:

-

educational and pastoral

-

faithful to the text

-

relevant and topical

-

orderly and comprehensible.

Pastor and Teacher in the Pulpit←↰⤒🔗

Teaching and Instruction←↰⤒🔗

Preaching is teaching; this has always been considered a most important element of the sermon. In fact, there have been times that the man in the pulpit was thought of first and foremost as a teacher. And it is true, you may expect to learn from a sermon; after all, that is the purpose of instruction.

It is remarkable how often the Bible itself speaks of teaching and instruction. Both the Old and New Testament point to teaching and instruction as the way to become familiar with the demands of a life before God, Particularly in His preaching, Christ, our LORD whom we acknowledge as our highest Prophet and Teacher, showed Himself the Master and that in the real sense of Teacher.2 This fact in itself provides sufficient reason to speak about the preaching in the church as teaching and instruction.

However, it will be obvious that we are speaking of a special type of instruction. Instruction may be thought of as merely a transfer of information. In this case the word instruction suggests that you wish to be informed about the important facts of a certain topic. We are familiar with this type of instruction from our experience as students in school.

It is clear that we may expect something else in the church. We do not attend here a course of study, not even a course in Bible study; neither do we receive here instruction in exegesis. In the church we hear how the God of our life speaks to us with His Word. Therefore we may and must expect something else from this type of instruction. The instruction received in the sermon never permits us to remain neutral listeners. We are fully, that is with our whole being, involved in the message which we hear. This also means that the instruction of the sermon must aim at the increase of the knowledge which is required for a life with the LORD.

Knowledge←↰⤒🔗

The instruction of the sermon aims at the increase of knowledge. Knowledge is essential for a true faith.3

The concept 'knowledge' can be defined in a variety of ways. In one sense it emphasizes facts: you want to know, that is, you want information about names, events etc. It is also possible to think of knowledge as actively using your brains. In this case you expect the sermon to be intellectually stimulating. Both these elements may well be present in a sermon, but they do not touch the heart of the matter. Faith is not a matter of formal knowledge, neither is it a matter of merely being informed about certain things. Faith knowledge can only exist within the intimate bond with God, a bond which He Himself has established. To know Him is to trust in Him.

Growth←↰⤒🔗

This has, of course, important consequences for what we may expect from a sermon. The point is not whether we hear something new and fresh, something we were not aware of before. No minister will be able to satisfy such an expectation. But more importantly, it ignores the fact that the core of the sermon is always known to us already, because we know Christ. Growth in the knowledge of Christ does not mean in the first place that we come to know more facts and information. It means that the bond between Christ and us becomes closer. Therefore, we may expect from a sermon that it will not be a lecture or speech about an interesting text, a difficult Bible book, or a disputed point from the confession. We may expect that the sermon aims at strengthening and deepening our relationship with Christ. The instruction of the sermon has only value and meaning when seen in this context.

Yet, this does not mean that the minister ought, in his sermons, to avoid as much as possible factual knowledge and difficult topics. What has been said so far is no plea for a minimizing of the content of the sermon. Indeed the argument is often heard that the preaching in the church should be as simple as possible. But that would mean that the minister could select only those Bible passages which are easy to understand and which readily speak to the congregation. The Bible certainly does not suggest at all that difficult matters should be shunned.

Our discussion so far tried to show the context in which these questions should be raised. Within that context we are called upon to exert ourselves with all our might (and also with our intellect).

We may therefore expect from a sermon that also difficult matters will be included in its instruction. If not, our faith would remain at an elementary level. The writer of the letter to the Hebrews speaks of this very point.4 He wants to go into depth about Christ as high priest after the order of Melchizedek (A careful reading of this letter gives the strong impression that the author is preaching!) Quite a few people find this letter rather difficult, something for the connoisseur. But if we truly love God, then we want to be busy also with this type of instruction, however difficult. This is certainly necessary in order to go on towards maturity. We should reject the false dilemma that true knowledge of faith has nothing to do with increasing our understanding of the instruction of the Bible.

The same applies to factual knowledge. When the sermon deals with e.g., Genesis 14,5 the minister will have to include some geographical detail about the land of Canaan. Without such information the main idea of this chapter is difficult to grasp.

Yet such geographical knowledge is only meaningful within the context of our faith and trust in God. In summary we may expect that the instruction of the sermon will make us wiser about everything that concerns our life before God.

Pastoral←↰⤒🔗

Secondly, we may expect that a sermon is pastoral; the shepherd speaks. Often people have difficulty understanding how a sermon can be instructional and pastoral at the same time. Some consider these two elements mutually exclusive. Such misunderstanding is promoted when we regard only the home visits of the minister as his pastoral activities. This is a wrong view of the work of the minister.

Being a shepherd means that the preacher lets the voice of the Good Shepherd be heard. That must take place on the pulpit! Separating the pastoral and the instructional element seems to suggest that we receive objective, non-personal instruction from the pulpit, while during the week the pastor attends to the personal needs of his sheep.

It will be clear from our discussion that such a division is not possible. We try to separate artificially what in fact are two inseparable elements of the one office. Both elements must work together in order to make the sermon into a real sermon, a ministering of God's Word.

A pastoral sermon seeks to win hearts while concretely addressing its message to the congregation. This can only come about when instruction and pastoral care form a strong and true unity. The minister will need to know his congregation in order to be a true pastor This knowledge will undoubtedly influence his sermons. Therefore instruction and pastoral care cannot be separated in a sermon.

Admonition and Comfort←↰⤒🔗

Further consideration of the pastoral element of the sermon suggests that the sermon must admonish as well as comfort. At first thought, this also seems a contradiction, but that is certainly not the case. (The Bible often uses the same word for these two ideas: admonish - comfort.) Admonition aims to prevent us from wandering away and losing sight of Christ. Comfort aims to ensure that we do not lose hold of Christ because of sorrow or other problems Admonition and comfort aim to keep the congregation with Christ.

This means concretely that we may expect that the sermon arms us against the devil, warning us against dangers equipping us so that we are able to fulfil our specific calling, encouraging us in real difficulties and temptations The pastoral element of the sermon means also that we may expect to receive clear instruction which will help us to come to know ourselves and our relation with God and the world around us better.

All this clearly shows that no division should be made between the pastoral and the instructional aspects of the sermon. The sermon's instruction can be to the point only when it is pastorally directed at the congregation. The pastoral emphasis of the sermon can only serve the congregation well when it is truly instructional.

All this has far-reaching consequences for the content of the sermon. The focus of this article was on the character of the sermon. Only when we have understood this character can we fruitfully discuss the content of the sermon in further detail.

The Text and The Sermon←↰⤒🔗

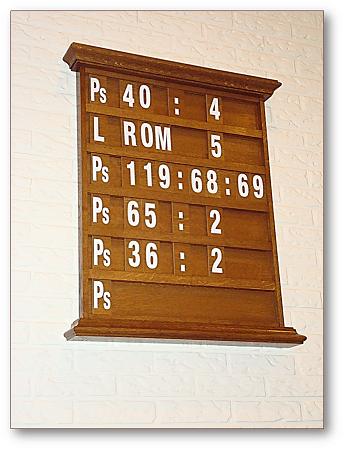

Usually the text is indicated on the psalm board in the church. If the sermon is to be actual ministration of the Word of God, then its contents must be determined by a portion of that Word. Fortunately, in Reformed churches it is self-evident that the sermon deals with the text indicated on the board. There are several aspects related to the sermon text which are of particular importance to the listener.

The Whole Bible←↰⤒🔗

The whole Bible forms the basis for the preaching. Since one sermon can in no way do justice to all of Scripture, we limit ourselves to a portion, the sermon text. This does mean that we should not lose sight of the whole Bible. It is indeed true that the congregation may expect that all of God's Word is ministered to her. Of course, no minister will be able to do this fully; not even a lifetime is sufficient for this. It does mean that the selection of the sermon text is not a matter of the minister's private choice. Certainly, every week he selects texts for his sermons, but he must consider and do justice to all of Scripture. Therefore we may expect that the minister adopts a guideline which helps him to organize the material for his sermons in such a way that he takes into account the whole Bible.

This can be done in a variety of ways. Two such possible frameworks to organize sermons are rather obvious: the Christian calendar and the Heidelberg Catechism. Each in its own way suggests an organizing principle for the selection of material for the sermons.

The Christian Calendar←↰⤒🔗

With the term the Christian calendar we mean the cycle of Christian feast days which commemorate important events of the history of salvation.

The Church Order regulates this in Article 53: Each year the Churches shall, in the manner decided upon by the consistory, commemorate the birth, death, resurrection, and ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ, as well as His outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

This instruction of the Church Order provides a natural way in which the material for the sermons may be organized from Christmas to Pentecost. The principle which is used here is the history of salvation. Obviously, many of these sermons will be based on the gospels. It is not without importance that we have received four gospels in the Bible which relate the facts of the history of salvation in detail. This is obviously a central point in the Bible. Therefore, we may expect to find this reflected in the preaching. We add, though, that it is not reasonable to expect a Christmas sermon on Luke 2 every year. Although this chapter contains a central point in the history of Christ's birth, the Bible has more to say about it in other passages. We may expect to hear that as well.

The importance of the Christian calendar has been questioned in the Reformed churches. Opponents have often cited the exaggerated emphasis on the cycle of feast days. In other denominations, each Sunday between November and June is given a different character. That is too much of a good thing. A varied arrangement of sermon topics based on the Christian calendar will help to make the congregation familiar with the significance of Christ's birth and work on earth. This will help to foster in the hearts of the believers the longing for His return. That is precisely what we may expect from a sermon.

The Old Testament←↰⤒🔗

Using the order of the Christian calendar will result in many sermons based on texts chosen from the New Testament, although appropriate passages from the Old Testament may be selected as well. This will be the case particularly in the period between Christmas and Easter.

However, this practice should not result in an overemphasis of the New Testament at the cost of the Old Testament. The New Testament is not available separately! It receives its meaning and significance from the Old Testament. Throughout the centuries, this insight has protected the church against many heresies. Therefore, it must bear fruit also in the preaching; otherwise the congregation does not learn to understand the significance of the interdependence of the Old and the New Testaments. It is important that this is emphasized today when the unity of the history of God's salvation is under attack from various sides. With the help of preaching based on the Old Testament, the congregation must learn to recognize clearly the unity of the Bible. This means that throughout the remainder of the year we may expect many sermons from the Old Testament. The second half of the year is a good time for that because of the absence of feast days.

Of course, we cannot and do not want to be prescriptive. (I value the personal privilege of choosing the text for the sermon.) However, the congregation may expect that in the longer term she receives systematic preaching from the Old Testament. The consistory may also speak to its minister about that. We believe that we have received the Bible because in it God describes at length the whole manner of worship which He requires of us.6 Therefore, this confessional insight demands that the preaching deals with the whole Bible, the Old and New Testament.

If certain books of the Bible remain closed on the pulpit, the congregation will be all too readily inclined to accept a much thinner Bible than the one entrusted to us by the Lord.

Planning←↰⤒🔗

From this discussion follows the obvious conclusion that a sermon text cannot be chosen haphazardly. Selecting such a text requires planning. This is already implied by the instructional character of the sermon.7 Every teacher who takes his work seriously uses a plan for his teaching because instruction requires structure and continuity. Since instruction from the Bible has the same characteristics, we may expect that a sermon also satisfies these demands. Therefore (do not believe in selecting sermon texts each week on the basis of certain events or needs in the congregation. This would show an overvaluing of the direct instructional character of the sermon.

The Heidelberg Catechism←↰⤒🔗

The Heidelberg Catechism provides us with an extraordinary method to arrange the content of the sermons systematically. The material is organized on the basis of the confession of the church. At times, people dispute whether a section of the catechism, a Lord's Day, can be the text for a sermon. The argument is that a sermon should be ministering of God's Word, while the catechism is the word of men. This is a false dilemma. The church has been diligent to indicate where these doctrines have come from. The church was able to formulate its confession by listening carefully to the Scriptures. When a sermon is based on the catechism, then the Bible is opened at all those places which the church has read in connection with the element of doctrine as summarized in that particular Lord's Day.

At this point I do not need to elaborate on the fact that we may expect regular preaching based on the catechism. I note here that the division of the catechism into fifty-two Lord's Days does not mean that the minister must complete the full cycle of the catechism in each calendar year. That would mean that a large part of the congregation will regularly miss the sermons dealing with the sacraments (because of the holidays!).

Further, the catechism does not provide an exhaustive treatment of the Christian doctrine. For example, much more could be said about God's election than may be done within the context of a catechism sermon. Since we confess that this doctrine must be taught to the congregation,8 we can expect that the sermon regularly demands our attention for this doctrine.

The Text as a Window←↰⤒🔗

So far we have only considered the choice of the text. That is only the beginning. How the text is worked out determines the whole sermon. Ultimately the sermon shall inform the congregation about her God, and shall minister His grace in such a way that it will become visible in the life of the congregation.

To achieve this, it must become clear that the text of the sermon is a window on the whole Bible, and in this way opens the way to God through His Word.

This means, very concretely, that the text must be explained carefully. Preaching is not a discourse on a variety of topics. It is the pointed speaking of God. To make this clear, the place and function of the text in the context of the whole sermon must be transparent, that is, clear and understandable. This is the first thing we may expect from the exposition of the text. If this is the case, then it will be obvious that the text was not selected because the minister wanted to get a particular message across, but because the Word of God must be ministered to the congregation. The preacher may, indeed, be tempted to do this. He might want to make a particular point and therefore select a suitable text. But then he ends up hiding his message in the sermon, while the question is ignored whether the text really says what the minister wants it to say. Thus the danger becomes real that the text is no longer a window on the message of God, but a vehicle for the ideas and opinions of the minister.

We may expect, therefore, that the sermon is faithful to the text. That means that the sermon shall put into words specific aspects of God's salvation about which the text speaks. Only in this way can the sermon be instrumental in bringing the congregation to Christ. And that is what we may expect from a sermon in the first place.

The question will undoubtedly arise at this point: What about the relevance of the sermon for today?

A Contemporary Sermon←↰⤒🔗

Churchgoers will readily agree: in church, we expect a sermon to be relevant and current. However, the agreement quickly ends when we try to determine the precise characteristics of a current sermon. Does the word current here mean the same as the current events with which the media presents us? Is a sermon current, when it deals extensively with political and social issues? Or should we remain closer to home and discover in the sermon all sorts of examples from everyday life? Or, perhaps, should the actual situation of the congregation be addressed in the sermon?

When thinking about the sermon as relevant and contemporary, we find ourselves wondering about questions such as these. On the one hand, these questions should not surprise us. After all, the sermon is not a timeless discourse. Yet, on the other hand, in such discussions we risk that our own feelings and views of the world become the guiding criteria for evaluating the sermon. It will take little persuasion to recognize that this could result in the rejection of much that, according to God's measuring rod, should be considered current and relevant.

The Bible and the Sermon←↰⤒🔗

To test our expectations, let us apply them to the Bible. No, the Bible and sermon are not interchangeable, but they may be considered from the same perspective.

When reading the Bible, we do not expect a message which gets its meaning from the actual situation we find ourselves in. On the contrary, we realize that we are reading words which were written more than twenty centuries ago. Yet we do not draw the conclusion that the Bible, therefore, is concerned with a message which is of no importance to us.

Nevertheless, people often complain that the Bible means nothing to them when they read it. It means so little, they say, because its message seems to come from a radically different world. Since our experience is unrelated to what we read in the Bible, we find it almost impossible to relate the two. For this reason, many people find it difficult to acknowledge that God indeed speaks to us today in His Word.

It is an easy and obvious step to desire, on the basis of such feelings, a sermon which translates the ancient message of the Bible into a message for today. A current sermon is thus one which redresses the old message in a contemporary form. In this sense the sermon in fact rewrites the Bible to make its message relevant to the situations today.

Is or Become←↰⤒🔗

We have reached an important question, namely, Is the gospel relevant, or does it become relevant today as it is passed on in the preaching? Without discussing in depth the theological background, it will be clear that the answer to this question is critically important for our understanding of the sermon as relevant and current.

There is no difference of opinion among us concerning the answer to this question. The Bible is relevant for today because in it God speaks to us. He thought of the generations to come, including our own generation, when He caused the apostles and the prophets to write down His Word.9

The Bible is not a book whose message remained hidden in the time of its creation. Indeed, the gospel breaks through all time barriers. We only need to remember that the life of the whole New Testament congregation falls fully within the expectation of the imminent return of Christ The relevance of the Bible for today has, therefore, always been emphasized.

It will be good to underscore this once again. I have found that many people find it difficult to read the Bible as relevant to their own situation and experience. They wonder in confusion what many Bible passages might mean to them.

Of course, we do live in a time in which people continually demand to know the relevance of what you say. When we try to answer that question from our twentieth century understanding and with our western minds, then we will produce an incredibly meagre answer. Everyone will recognize this, when we think of "tomorrow" which will follow "today." Tomorrow many changes will take place; other things will determine the face of the world and occupy the thoughts of the people. What was current and relevant yesterday seems so much less important today. Considering this, our thoughts and relevance and importance are tempered considerably, and we will begin to speak much more carefully.

The Bible teaches us to acknowledge the riches of its message which encompasses all ages. When we try to speak of relevance and importance within the context of this rich and enduring message of the Bible, we must consider much more than what we see today with our limited human vision. This is not only so because God's Word has sufficed for God's children throughout all the ages, also in times other than our own. The Bible's message is so rich and enduring because in this Word God makes Himself known to His people. His grace is relevant and important in our lives. This relevance cannot be measured in terms of our limited, time-bound understanding; it is determined by God's eternal purpose.

It will not harm us to think about this when reading the Bible or listening to a sermon! It will protect us against the danger of limiting, perhaps even belittling what God wants to give us.

Those who want to hear only a contemporary message will lose sight of that which is for all ages.

The Address←↰⤒🔗

It will be clear that the eternal Word and the actual congregation are not two equals between which the sermon must unfold. The source of the sermon is the Word of God, not the congregation. The relevance of the sermon is, therefore, not determined by the situation within the congregation, but by that Word. For this reason I do not believe in selecting the sermon text on a weekly basis, in response to certain happenings and preceived needs in the congregation.10 The minister who selects his text in this way will find his sermon "in the congregation." In this case his understanding of the situation of the congregation determines the relevance of the sermon. The risk is great that minister and congregation become quite shortsighted when they are busy with the gospel in this way.

The question arises: What is the address of the sermon? The sermon is directed to a particular congregation at a specific moment in time. The previous discussion does not imply that the congregation, as the address, is of no importance to the sermon. The Bible shows us how apostles and prophets carefully directed and focused the message which they were called to bring to God's people. However, the relevance of the message is not found in that focusing, but in the Word itself. Only in this way will we find a starting point for a relevant, topical, contemporary sermon.

Here we have found the framework for the sermon, but within this framework the message needs to be directed and further focused. Since a sermon is the ministering of the Gospel, we may expect such focus and direction.

Contemporary←↰⤒🔗

The question about the direction and focus of the sermon is related to the whole worship service. We believe that the worship service is an important meeting with God within His covenant relationship with His people. Therefore it is most important that this meeting is not a strange, unusual event in the life of the congregation. Further, the God who comes to the congregation with His eternal Word is and wants to be her God today. In this way the worship service becomes a real meeting of the Head of the church and His people.

What happens in the church has everything to do with what happens in the world, because the Head of the church is the King of this world. This means that the worship service cannot and may not be a place of isolation where the congregation withdraws herself from this world. The congregation needs to learn this fact in the church. She must clearly understand that the worship service has everything to do with the everyday life of the congregation. We may expect that within the framework of the relevance of the gospel, the message of the sermon is clearly focused on our own time and situation.

In church, we may expect a contemporary sermon. What is contemporary? This concept demands further explanation. Many things and ideas present themselves as contemporary. However, within the framework of our discussion I may identify at least two aspects: the sermon will have a date and it will have an address.

First, the date of the sermon is important. Of course, not in the sense that a week earlier or later matters. What matters is that the sermon is clearly related to the times in which the congregation lives. The congregation must learn to understand what it means to live as congregation of Christ in the 1990s. She must learn to discern what moves today's world, and in particular what motivates the people of today. Every day the congregation finds herself eye to eye with the world. It becomes vitally important that she will be able to discern clearly what is and what is not from God. She must be enabled to deal with today's questions in word and deed. Therefore we may expect the sermon to provide insights which help the believers to discern what is of importance in their lives before God in today's world. This understanding results in sermons with a date, and that is certainly no disadvantage! It shows clearly the difference between the Bible and a sermon. The Canon of the Bible is complete. However, since every new period places new demands on the congregation to live in the world of that day, our ministers continue to make new sermons.

Not only is the date of the sermon important, also its address needs our attention. The sermon does not direct itself "to whom it may concern," but to a particular congregation. In the sermon, instruction and pastoral care go hand in hand. It is remarkable that the message of the apostolic epistles and the letters to the seven congregations is so clearly addressed to particular congregations. Thus, the message of the gospel is not determined by the congregation, but it is applied concretely to the situation of that particular congregation.

Application←↰⤒🔗

We came across a word which is often used in connection with the sermon: the application. I realize that this is a topic about which much more could be said. I leave much undiscussed, since it is not my intention to be complete, but rather to provide some assistance when we speak about the sermon. Therefore I can only make a few remarks in the context of these articles.

Many consider the application the most important factor in judging a sermon. In this way the sermon's application becomes somewhat of a hallmark of a relevant, worthwhile sermon. Such reasoning is based on the misconception that the message becomes relevant only if it is applied to our time and our situation. Perhaps certain practices have encouraged such thinking. For quite a long time sermons were often based on the principles of explanation and application.

Such sermons would first explain in detail the text itself. Then they would continue with the application in which the message-for-today was spelled out. In times past these two segments of the sermon were often separated by congregational singing of an appropriate psalm or hymn.

It should not surprise us when such practices lead to a lack of understanding and appreciation of the worship service as a meeting with the Lord. These practices suggest that before the congregation really can hear in the preached Word how the Lord gives Himself; the Word needs to be actualized, applied to the present situation.

The application of the sermons should never be a separate section of the sermon, as if only this segment is important for today. If this is done, the impression is given that sermons are current only in as much as they deal with political, social, or ecclesiastical "current events." Neither should the sermon attempt to "address" the congregation with a wide range of practical examples taken from the life of the congregation.

Such practices do not guarantee the relevance and value of the sermon for today. For a sermon to have a date, it does not need to deal extensively with the issues of the moment. What is necessary is that a sermon builds up a Christian perspective on such current questions and issues.

In order for the sermon to have a clear address, it is not necessary that it deals in depth with the problems of the particular congregation. A sermon with a clear address provides the congregation with concrete help and support in dealing with matters of concern.

Therefore, the sermon's application cannot be a loose-leaf addition to the discussion of the text. We may expect that, throughout the exposition of the text, a contemporary sermon shows how the eternal Word of God must be applied in our situation and in our time.

A Comprehensible Sermon←↰⤒🔗

Is the structure, the presentation, and the form of the sermon important? Many believe that only the content is important. If the content is alright, then the rest does not really matter.

That is another misconception. Form and content cannot be separated. Further, the structure and presentation of the sermon is of great importance for the listener. When the sermon has been carefully put together, its message will be so much easier to understand. A sermon should address the congregation, and therefore its form must enable it to speak to the congregation.

A sermon poorly and carelessly put together will form a barrier for the listener. We all know of sermons which make listening difficult. When the importance of the presentation is ignored, the sermon may become boring. It is not a light thing when the truth is made into a boring event!

Therefore, we may expect that the structure, presentation, and form of the sermon contributes to the ease and effectiveness of the listening. The first consideration is then, that we may expect an orderly sermon.

Theme and Points←↰⤒🔗

To help the listener, the sermon should have structure. This applies to every speech. No speaker who considers his message of value and who takes his audience seriously will dare to present a tale which makes little sense. We may certainly expect that a sermon is carefully structured.

It is already an old custom in Protestant churches to capture the structure of the sermon in a theme with accompanying points. However, nowadays this is no longer the practice in many denominations. In general, thematic preaching has been discarded. This is only in part caused by shorter sermons which simply do not leave enough time to develop a theme.

Thematic preaching is certainly not the only way in which the sermon can be structured. Its advantage is that the preacher is forced to clarify the structure of the sermon and to present this to the congregation. This gives the listener an excellent outline to follow the development of the sermon. The preacher must certainly know what he is doing if he does not want to make use of this opportunity. Although there are preachers who can do without, experience tells us that many sermons become rather disorganized in the absence of a theme and points.

The formulation of a theme demands that the content of the text is concisely summarized. The points help to identify clearly the various elements in the text. Therefore this method remains important to structure the sermon clearly and understandably. That is what we may expect from a sermon, also when the minister does not use a theme with points.

How Long?←↰⤒🔗

Often the question is asked, how long should a sermon be? This question is not only motivated by the fact that our listening ability is severely hampered by the strong emphasis on the visual in our time. The length of the sermon is also related to its structure.

I would like to plead for a short sermon. I do not mean that a sermon should not be longer than half an hour, or perhaps twenty minutes. The one minister needs much more time than the other, even though they may say the same. The one speaker uses more words than the other. Further, the length of the sermon depends on the text. Therefore, I do not want to prescribe a time limit. I speak of a short sermon. The congregation does not always benefit from all sorts of excursions and elaborations. These do not help the clarity and structure of the sermon, but obscure the message and hinder comprehension. The congregation must be able to follow the sermon readily. Therefore, the sermon must be direct and purposeful, without too many detours. That purpose is determined by the text. We may expect a short sermon, so the congregation is able to follow the preacher readily, and understand the purpose of the sermon.

Reading or Speaking←↰⤒🔗

Should the minister preach from memory, without reading from his notes? Many consider this to be the best way of preaching. And indeed, it is a joy to listen to a speaker who is in such full control of the material that he is able to present it without reading from his prepared speech, captivating his audience in the process. Listening becomes more difficult when the minister reads from a printed sermon, with little thought of the audience.

There are, on the other hand, reservations about preaching without a written-out sermon. Experience shows that a speech becomes longer if its text has not been determined before. This is often obvious towards the end of the sermon, when the minister takes time to search for a "nice" ending. More important is the actual formulation. Since a sermon is the ministering of God's Word, we may expect that the formulation has been prepared with great care. Historically, the church has always paid much attention to the manner in which she echoed God's Word in her confessions. This careful attention should apply equally to the formulation of the sermon. Therefore, the formulation of the sermon may not depend on the inspiration of the moment, or on the preacher's ability to improvise. We may expect that (most of) the text of the sermon in its main thoughts has been prepared before the worship service starts.

Easy or Difficult?←↰⤒🔗

How difficult may a sermon be? Does it always have to be an easy one? What, in fact, is a difficult sermon?

At this point I am not concerned with the content of the sermon. Consideration of the content makes us think of the elementary elements of faith and of growth in insight in God's Word. This aspect was dealt with when we spoke of the instructional aspect of the sermon.11

I am concerned here with the level of difficulty in the formulating of the sermon. This depends on the preacher and on his audience. The minister, as a person, is a factor which cannot be ignored. The one can deal with difficult Bible passages in a clear and easy manner, while the thought patterns of another are much more complicated. We will always be able to find personal elements in all sermons. There are limits to the extent in which individuals can develop in their ability to express themselves. The congregation also remains a decisive factor. The average churchgoer will have to understand the main thoughts of the sermon in order to have access to its message.

This does not mean that all listeners should be able to retell the sermon completely. On Mondays, many people are unable to tell anything about, let alone retell, the sermons of the previous Sunday, although they listened attentively and with a desirous heart. We cannot measure exactly what we have received in the sermon and what its effects have been on the basis of what we remember. That would be an overemphasis of the importance of intelligence. In church, we are also busy with the heart!

I spoke on purpose about the main thoughts of the sermon. I do not believe that we should demand that every churchgoer will understand in equal measure every detail of the sermon. In that case we would get a sermon for the greatest common denominator.

Such a sermon could easily impoverish some people. Although instruction is directed at a certain average, I recommend that the sermon contains elements which may not be noticed by all, but may be stimulating to some. These are the important raisins in the instructional porridge, a piece of old pedagogical wisdom often forgotten today.

We may, therefore, expect that the difficulty level of the sermon is such that its listeners are stimulated to continue to work with the ministered message of the gospel.

Speaking, Preaching, Listening←↰⤒🔗

In these articles we dealt with the question what we may expect from the sermon. I believe that this is an important topic to speak about with each other. I have only dealt with major elements. Much had to be left out because of the limited space available.

The discussion of the sermon is also important in our houses and certainly in the consistory rooms. I have written these articles to stimulate such discussions, because I know that many are hesitant, and uncertain about what they should talk about when discussing the sermon.

In conclusion, it may be necessary to emphasize again that such a discussion can be fruitful only when it is based on real listening. Only those who really want to listen to what God has to say can sensibly speak about the sermon. Otherwise, hollow words will be spoken. That should not happen when we discuss the sermon.

When our discussions are fed by a genuine desire to listen to God's Word, we also want to listen to each other when speaking about the sermon.

This will certainly benefit the preacher and the congregation.

Add new comment