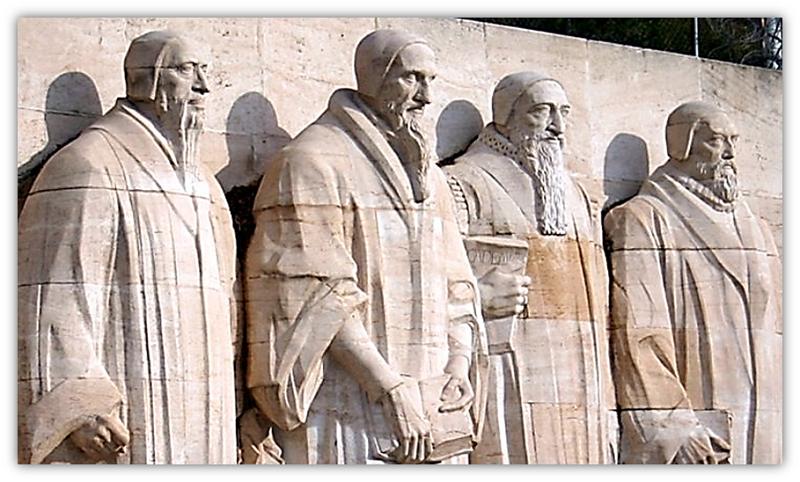

Reformation and Mission

Reformation and Mission

"Minus the Apostles?"⤒🔗

More than once it has been said by historians (and not only be adversaries of the Reformation but also by some who belong to Reformation circles) that it would be possible to write a complete history of Reformation times without even using the word mission. The Reformers, they say, did lot of good things in all respects, but they did not do anything concerning mission. The whole matter of mission was something done in Reformation times by the Roman Catholics, and the churches of the Reformation discovered the importance of mission no earlier than about a century later.

It is also said that actually Pietism awakened the call for the great commission to go out and to bring the gospel to the gentiles.

In Germany they used for that so-called lack of mission the word "Mission-slauheit" (lukewarmness regarding mission) and they apply that word to Luther and to Calvin as well.

Many of those writing concerning this matter have stated that the Reformers (and they apply that especially to Luther and Calvin) wrongly believed that the missionary mandate of Matthew was limited to and fulfilled in the apostolic era. Dr. J, Verkuyl writes in his book Contemporary Missiology for instance.

It is incomprehensible that the Reformers and their contemporaries did not relate Jesus' promise in Matthew 28 to be present even to the end of the age to the fulfillment of their missionary task, but it is undeniably true.

In the circles of the ecumenical movement is even said, "Calvin made the most amazing mistake for an able man when he tried to reform the church by reconstructing it after the pattern of the apostolic age minus the apostles. The Spirit that has directed the history of the primitive church was wiser than Calvin." E.J. Palmer on the Conference on "Faith and Order," at Lausanne, 1927

The conclusion is that the Reformers themselves did not encourage the sending out of missionaries or contribute to the theological study of our missionary task. The missionary consciousness had to wait until a later time and was initiated only with the coming of the so-called further Reformation and Pietism. "Then actual Protestant participation in world mission and the theoretical reflection upon this activity really began" (Verkuyl, ibid.). But as far as the Reformers themselves are concerned, there is not to be found even a latent missionary zeal: there is a complete vacuum in this respect.

Complete Vacuum?←⤒🔗

What to say about these reproaches?

-

In the first place, it is unfair as well as scientifically inadmissible to summon the Reformers before the tribunal of a modern missiological concept, which has itself its historical limitations and its theological defects. In his dissertation, Constrained by Jesus' Love, J. van den Berg points to this answer of especially some Lutheran authors, and he adds, "Too often indeed, missions have been identified with the 'business of missions,' with the organizational aspect of modern missionary life," (p. 5).

-

In the second place, when the Reformers give sometimes the impression that it was the special task of the apostles to proclaim the gospel to the gentiles, we have to consider that they said that over against the "apostolic succession," as if the Pope of Rome were the direct successor of the Apostle Peter. I give two quotations of Calvin's Commentary on Matthew 28:19 and 20 in this respect:

So we learn that the Apostolate is not an empty title of honour, but a responsible office; and that there is nothing more absurd not more intolerable than that false men should usurp the honour to themselves, live at ease as kings, and do away with their responsibility to teach." And concerning the last verse of the gospel according to Matthew, "We must note that this is said not only to the apostles, for the Lord promises His aid not to one age alone, but to the end of the world. It is precisely as if He said that, whenever the ministers of the gospel are weak, and labour under the lack of everything, He would be the Guardian, so that they may come out victorious over all the world's conflicts. Thus today clear experience teaches that Christ works in a hidden way, marvellously, and the gospel prevails over numerous obstacles. All the more intolerable is the sin of the papal clergy, who make this a pretext for their sacrilegious tyranny. They claim that the church cannot err, being ruled by Christ, as if Christ, like a common soldier, hired Himself as mercenary to different leaders, and did not keep His authority firmly to Himself and declared that He would defend His doctrine, so that His ministers might confidently expect to be victorious over the whole world.

So this is to be said in the first place: that the Reformers stressed the unique place and task of the apostles and that they denied the claim of the Pope to be the successor of the apostles.

But there is more. He who reasons that there was a complete lack, a vacuum in respect of the idea of mission in the mind of the Reformers, is absolutely wrong. Let us start with the main Reformers, Luther and Calvin.

Luther Over Against Turks and Jews←⤒🔗

We start with Luther, the first in chronological order. It is an evident fact that Luther placed himself also in missionary respect over against the Roman Catholics of his days. When Luther discovered the accent on human activities in Roman Catholic mission work, he stressed that mission work is in the first place the work of God Himself. Christ is the Head of the church, He leads her, He saves her, He sanctifies her, He purifies her, but He also increases her. He edifies and preserves His church and He uses for that purpose each and every member of the church. Luther says, "Jeder einzelne Christ ist dazu bestellt, dem anderen ein Christus zu werden." That means that all Christians have to be involved in the spreading of the good news of the gospel. Actually Luther here said important things in respect of what is called later on home mission, but this also has to do with mission as such.

Speaking about Acts 8 where it is described that the eunuch, a minister of Candace the queen of the Ethiopians, was converted and being baptized, Luther said he could not imagine that the eunuch would not have propagated the gospel of Jesus Christ in his native land.

As far as the Turks are concerned, it is well-known that Luther was very sharp over against them. But is it also known that Luther reproached the Pope in Rome that he had undertaken crusades against the Turks (or the Moslems) but that he did not bring the gospel of Jesus Christ to them? That would be the first mandate for the Pope, according to Luther: To let the Moslems hear the Gospel of our only Saviour Jesus Christ! Another example concerning the Turks!

In Luther's time there were Christians made captives by the Turks in Eastern Europe. Then Luther said: These captive Christians have the important task to bring these Turks who are Moslems in contact with Luther's Catechism.

I ask, what else would that be if not mission work?

As far as the Jews are concerned, Luther mentions them often in one breath with the Turks, not as alien races, but as peoples who consciously deny Jesus Christ, who trust in their own human power and who expect everything from their own merits. In the first years after the Reformation of the church, Luther had a benevolent attitude over against the Jews. He had the firm expectation that they would be converted to Jesus Christ, now that the gospel had been brought to light again. He regarded it as an evident fact that the Jews had not found the glory of the New Dispensation during the dominion of the Pope:

The papists behaved themselves in such a way that, being a Christian, one should rather become a Jew than the other way around. If I had been a Jew, I would have preferred to become a pig rather than a Christian.

Luther was the first one who understood that the gospel had to be brought to the Jews, because this people in the first place have rights to Christ. In this way came into existence what is called Luther's mission book That Christ is a born Jew. He cooperated with Jewish scholars and used their knowledge of the Hebrew language in order to understand the Jewish background the better. Luther discovered also that the Jews had come to their trade in money, to their practice of usury especially as a result of the attitude of many Christians who did not leave to them any possibility of life. But that, he hoped, would be changed: "All Israel will be saved." It was a bitter experience for Luther when he saw that things developed in a totally different way. He took offence at the Jewish mockery of the Messiah of the Christians, and when he heard that in Bohemia a number of Christians had become Jews, he wrote some very extreme statements against the Jews, "Ultimately," the Lutheran Dr. W.J. Kooiman says, "it was a kind of 'harsh mercy' and it was an attempt to save those who would be willing to be converted." These severe statements were regrettable and they caused much evil. But let us bear in mind that Luther was absolutely not an anti-semite. From Luther is also the prayer:

Oh God, heavenly Father, please turn aside and let Thy wrath be satisfied over them for the sake of Thy beloved Son Jesus Christ. Amen.cf. Luther, Zijn weg en werk, p. 171

Eschatology←⤒🔗

More than once it has been said that Luther was so strongly convinced that Christ would come back very soon that there was no room in his theology for missiology. It has also been said that Luther had the idea that it was not worthwhile any more to go out with the Gospel because of his eschatological ideas.

Indeed, Luther had the conviction that Christ's return on the clouds of heaven was not very far off. But it is absolutely wrong to derive from that fact that Luther had objections against mission work. Precisely in the tension of Christ's coming back, we have to fulfill our task. Luther often called the day of Christ's return the "sweet last day." But he said at the same time, "If I knew that Christ would come back tomorrow, I would still plant a tree today."

Conclusion Concerning Luther←⤒🔗

When we take account of the circumstances of Luther's times, of the struggle over against the papal clergy, also of the fact that there was a close connection between church and state and that it was almost impossible to go abroad with the Gospel, our conclusion must be that it is totally wrong to say that Luther did not see anything of the mission task of the church.

Calvin←⤒🔗

In the first part about Reformation and Mission I paid special attention to Luther and I said that its absolutely wrong to say, as many authors do, that Luther did not say anything concerning the Scriptural calling with regard to mission work. Some point in this respect especially to the Reformers' exegesis of Matthew 28:19, as if Luther and Calvin were of the opinion that the apostles had already done all the mission work, so that actually nothing was left for later times. But I stressed that we have to read Luther and Calvin in the context of their writings and, as far as this text is concerned, that over against Rome they very sharply rejected the idea of the apostolic succession.

At the same time it can be said that there are several places in Calvin's Commentaries on the Bible and also in his Institutes where we can see that Calvin did indeed have the idea that mission work had to be done and that it was not finished at all.

Let me mention first some texts of the Old Testament. In his Commentary on Isaiah 12:4 and 5, the Reformer writes,

He [the prophet Isaiah] means that the work of this deliverance will be so excellent, that it ought to be proclaimed, not in a corner only, but throughout the whole world. He wished, indeed, that it should first be made known to the Jews, but that it should afterwards be spread abroad to all men. This exhortation, by which the Jews testified their gratitude, might be regarded as a forerunner of the preaching of the gospel, which afterwards followed in the proper order … We ought especially to be inflamed with this desire, after having been delivered from some alarming danger, and most of all after having been delivered from the tyranny of the devil and from everlasting death.

He continues his exhortation by showing what is the feeling from which this thanksgiving ought to precede; for he shows that it is our duty to proclaim the goodness of God to every nation.

While we exhort and encourage others, we must not at the same time sit down in indolence, but it is proper that we set an example before others; for nothing can be more absurd than to see lazy and slothful men who are exciting other men to praise God.

This is nothing else than the fervour of Calvin in seeing the duty of mission work as "proclamation to every nation."

Also in his Commentary on the last book of the Old Testament, the prophecies of Malachi, Calvin stresses more than once that God's Kingdom is not complete yet but that it is growing and increasing also in our times and that we also are involved in that continuation of God's Kingdom.

New Testament←⤒🔗

In his commentary of the Gospels, Calvin mentions in respect of Matthew 24:14, "And this gospel of the Kingdom will be preached throughout the whole world, as a testimony to all nations; and then the end will come," that there are "antipodes" and other far removed peoples, whom even the last fame of Christ has not reached. So the gospel of the Kingdom must be preached to all nations!

In a similar way we can read Calvin's opinion concerning the spreading of the gospel in his commentary on the letters to Timothy. In connection with 1 Timothy 2:4 he writes:

The Apostle simply means that there is no people and no rank in the world that is excluded from salvation; because God wishes that the gospel should be proclaimed to ail without exception.

Also Calvin's similar comments on the second letter to Timothy and the letter to Titus are to be mentioned, let alone what he said more than once in sermons on texts of the New Testament.

Institutes←⤒🔗

It is repeated many times in all kinds of books that Calvin said in his Institutes that the whole matter of mission had been finished at the end of the apostles' times, I said already that Calvin was of the opinion that there are no direct successors to the apostles, over against the ideas of the popes that they esteemed themselves as such, Calvin denied the "apostolic succession" and stressed that the office of the apostles was a very special and extraordinary office. But in the same context of his Institutes in which Calvin stressed this, he also added: "Although I deny not, that afterwards God occasionally raised up Apostles, or at least Evangelists, in their stead, as has been done in our time" Inst. IV, 3, 4

Time and again it is to be read in Calvin's Institutes that it is our duty to proclaim God's goodness all over the world, and there are many places in the Institutes in which Calvin points to the fact that the heathen nations may be involved in the whole matter of salvation. It is also repeated time and again that especially in his Institutes Calvin put so much emphasis on the doctrine of election that this doctrine is not to be combined with the idea of mission. This would then be a kind of "theological excuse": because of the accent on election and reprobation, the Reformed would have locked the door to mission work. But he who carefully reads the whole part on the divine election and reprobation in Calvin's Institutes (III, 21-24) sees immediately that this argument misses any foundation.

Quoting Augustine, Calvin assures us, "Because we know not who belongs to the number of the predestinated, or does not belong, our desire ought to be that all may be saved; and hence every person we meet, we will desire to be with us a partaker of peace" Inst. III, 23, 14

It is true that Calvin discerns between general and special calling. The general calling has to do with the outward preaching of God's Word, and the special calling is the work of God the Holy Spirit through which the preached Word of God is attached in the hearts of men. But nowhere the conclusion is to be found in Calvin's Institutions that the Word of God is not to be proclaimed and to be preached to all nations.

Prayers←⤒🔗

Not only have many sermons (more than 2000) of Calvin been preserved, but also many prayers at the end of the sermons. Often these are prayers which have to do with the further propagation of the gospel. Then Calvin prays that the Word just preached may not only reach its goal in the hearts of the hearers, so that the congregation may bear many fruits, but also that the Word of God may be preached elsewhere and that it may also reach the hearts of the ignorant and those who have gone astray. In no way can one conclude from Calvin's prayers that the Reformer had no insight into the work of mission. On the contrary: many times he prayed that the gospel might be spread throughout the world.

Geneva←⤒🔗

When we have a look at the immense amount of work Calvin did in Geneva, we may even conclude that Geneva was a kind of mission centre. From all parts of Europe the students came to Calvin's city in order to be instructed in what he called the "pura doctrina," the pure doctrine of the gospel. And after having studied there, they spread the gospel over Europe, in many countries.

Some have objected more than once that this was only the preaching of the Word in countries which were already more or less Christianized. But when we take into account how terrible the ignorance of the people was, we may say that it was indeed mission work, namely to bring the gospel of Jesus Christ to the people that did not know its most elementary principles.

Besides, from Geneva Calvin wrote hundreds and hundreds of letters to many people in Europe, also to encourage the propagation of the gospel.

No Attempts?←⤒🔗

Some have said, All right, but are there indeed attempts by the Reformers to go out with the Gospel and to proclaim the good tidings to the gentiles?

-

Now first of all I can point to what Luther said about the Jews and the Turks and how the people had to contact them.

-

In the second place I can repeat that Calvin had much influence in the whole of Europe and that there were many contacts in many countries.

-

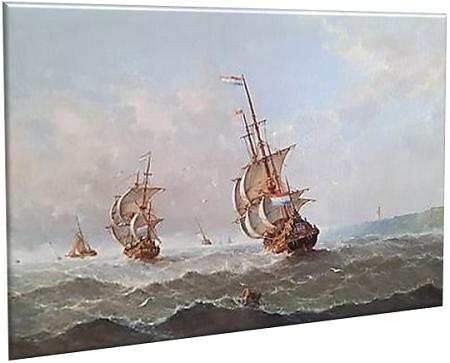

In the third place it must be said that in Reformation times the trade routes were especially in the hands of Spain and Portugal, Roman Catholic nations, so that it was almost impossible for the German, French, and Swiss people to go outside of Europe.

-

But last but not least, in the fourth place: there was indeed a very important attempt at mission work in Calvin's times, namely in Brazil.

The Mission Venture in Brazil←⤒🔗

I already mentioned that there was a very important attempt at mission work in Calvin's time, namely in Brazil. This attempt was strongly promoted by the Reformer himself.

The French nobleman Gaspard de Coligny, who would become later on, in 1572, a martyr in the terrible massacre of Bartholomew's day, conceived the project of planning to send ministers to a French colony in Brazil. The goal was not only to support the colonists in spiritual respect, but also to bring the gospel to the Indians in order to convert them to faith in Jesus Christ. De Coligny was in contact with a certain De Villegaignon and he influenced the French King to allow De Villegaignon to sail out with two vessels to the new world. It was principally Protestants who accompanied him. De Villegaignon was also in contact with Calvin. In November, 1555 the expedition arrived at Rio de Janeiro. In the beginning they had a very hard time. There were dangers from two sides. The Portuguese, who claimed to have authority over that area, were very hostile, and the natives were also very dangerous. Disappointed and discouraged, some of the colonists returned to France. With those who remained, De Villegaignon took up his residence close to the coast on a small island which he gave the name "Coligny."

Request for Ministers←⤒🔗

Already after a short time, De Villegaignon sent letters to De Coligny and to Calvin in which he asked them to send some preachers and also more colonists "in order to come to a firmer establishment of the colony and to a further expansion of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ." Then two preachers were delegated from Geneva, the first one was Peter Richer, a doctor of theology, and the second one was William Chartier. These ministers departed from Geneva on September 8, 1556. Several people accompanied them. Altogether there were thirteen who were willing "to bring the Kingdom of Christ to the new world." In France they find many Huguenots who dared to undertake the venture with them. In this way a group of three hundred people was gathered at Honfleur and they departed with three ships on November 19, 1556. On the tenth of March 1557 they arrived in the colony.

Great Expectations←⤒🔗

There is a double report concerning the first three weeks after their arrival: letter of Richer to an unknown person and also a letter of Richer and Chartier together to Calvin. Especially the last letter gives us an insight into the relation in which Calvin stood to these men and their work. It appeared that they were very closely connected with the Reformer.

They wrote to Calvin, "Our fellowship in which we are connected by the Holy Spirit to the body of Christ, unites us together so strongly that the enormous distance which separates us, cannot hinder that we are with you in the Spirit, in the certainty that you also bear us in your heart."

In order to strengthen this fellowship, they want to let Calvin participate in their sorrows and joys. They are very happy with the way they were received by De Villegaignon. They call him their father and brother and they expect much from him and from his work. They have hope that rather soon a big congregation can be instituted to proclaim God's praise and extend Christ's Kingdom. At the end of their letter they ask Calvin's intercession for their work of mission, "in order that God may complete this building of Christ at this end of the earth." The church of Geneva gave thanks to God on these favourable messages from Brazil, "for the extension of Christ's Kingdom in a country so far away, on a piece of the earth so strange and among a nation which seems to be totally ignorant of the true God."

In Richer's letter we find more data about the religious life of the natives in and around the colony. He portrays the life of the natives in very dark colours. The summing up of the sins and misdeeds reminds us of what the apostle Paul writes in Romans 1. How can the preachers of God's Word get access to such people? Besides, they stand before an almost insuperable language barrier. Yet they do not despair. "Because the highest God Himself entrusted this office to us, we hope that one day this country of Edomites wilt become Christ's dominion."

Treason←⤒🔗

But the great expectations of these missionaries proved false. It appeared that De Villegaignon was not the man he was supposed to be. After the first celebration of the Lord's Supper, quarrels broke out in circles of the colonists. Some of them were in favour of bringing more Roman Catholic elements into the celebration. Their spokesman was a certain Cointa, who had studied at the Sorbonne University at Paris. De Villegaignon sided with him, after having first sent Chartler to Geneva in order to ask Calvin for advice. Especially a letter from the cardinal of Lorraine caused him to conduct himself harshly over against the Protestants. Finally, their worship services had to be held in secret, just as in their fatherland. In this way the original attempt to build a Protestant colony as a centre of mission work among the heathen originals was frustrated. In this situation a group of them wanted to go back to France. De Villegaignon expelled them from the island. They fled to the continent of Brazil, where they tried to contact the aboriginals. They also attempted to bring the Gospel to them. One of them had already penetrated so far in their language that he could give them a small dictionary of the language of the "Topinambu," as they called them.

Return←⤒🔗

But the refugees could not hold out for a long time. All kinds of hardships finally caused their return to France. Some of them preferred to go back to the colony. But De Villegaignon condemned them as heretics. One of them escaped, four others testified to their faith in a courageous way. The result was that De Villegaignon had them thrown from a rock into the ocean. The names of these first martyrs of Reformed mission deserve to be mentioned: Pierre du Bordel, Matthieu Vermiel, and Pierre Bourdon. It is a bitter thought that these martyrs did not fall as a consequence of the resistance of the Gentiles, but by the perfidious treason of a fellow Christian. De Villegaignon spared the life of the fourth one, because he could serve the colony with his handicraft, according to his opinion. Those who stayed on the ship safely reached the French coast. Richer became a minister of the church at La Rochelle.

The colony was deprived of its best men, so it could not hold out either. De Villegaignon returned to France and remained an enemy of the Reformation for the rest of his life. He died just before the year of the martyrdom of Gaspard de Coligny. However, he did not die as a martyr, but in the greatest misery…

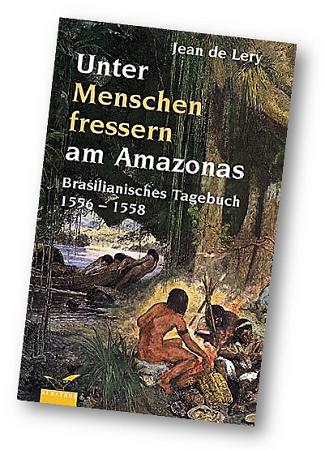

One of the fellow travellers, Jean de Lery, described the whole journey extensively and when later on his book was reprinted, he dedicated it to Louise de Coligny, the daughter of Gaspard de Coligny.

Louise de Coligny was the fourth wife of William of Orange, who survived her husband. De Lery mentioned in this dedication "the reverent remembrance of the Prince of Orange." In 1569 he had met the Prince, being delegated to thank him for the defense of the French Reformed churches, which he had undertaken with great sacrifices. On that occasion Prince William had answered that he wished he could do more for the service of the Lord and of the churches on behalf of which the delegates had spoken. So also the name of Prince William I of Orange is mentioned in the report concerning the first Reformed mission venture!

Calvin to Farel←⤒🔗

Calvin was closely connected with this attempt at mission work. In his letter to his friend Farel, he wrote on Feb. 24, 1558, about De Villegaignon as someone "who was sent by us to America ('a nobis missus fuerat'), where he has treated the good matter in a bad way because of his immeasurable hot-headedness." Calvin wrote this letter about six years before his death. He deplored it very much that these first attempts at Reformed mission work in Brazil was not a success. But the failure was definitely not due to the Reformer himself. He encouraged the planning of De Coligny. He sent missionaries to the colony. He functioned as their spiritual father and gave his advice. They brought before him all their troubles and sorrows, and Calvin's encouragement gave guidance to their work.

Our conclusion is that also in practical respects Calvin very much promoted mission work, although prospects were not favourable.

Propagation of the Gospel←⤒🔗

We discovered that – in spite of all kinds of criticism – Calvin strongly promoted the work of mission, also in practical respects. He also encouraged others to propagate the gospel, and he was very grateful when he discovered that the propagation of the gospel met with success.

He wrote his dedicatory epistle to the first edition of the second part of his commentary on the Acts of the Apostles "to the most serene King-elect of Denmark and Norway, Frederick" and said at the end of it,

I shall touch on one thing which is appropriate for a royal personage. When the power of the whole world was in opposition, and all the men who had control of affairs then, were in arms to crush the gospel, a few men, obscure, unarmed and contemptible, relying on the support of the truth and the Spirit alone, laboured so strenuously in spreading the faith of Christ, avoided no toil of dangers, remained unbroken against all attacks, until at last they emerged victors. Accordingly, for Christian princes, distinguished as they are by a certain authority, since God has provided them with the sword for the defence of the Kingdom of His Son, there is no excuse for not being at least just as spirited and faithful in the discharge of such an honourable task.

Under the pressure of the Lutherans, Frederick refused this dedication of the 1554 edition. So Calvin dedicated the second edition of 1560 to Nicolas Radzivil, "duke in Olika, palatine of Vilna." But that does not diminish the well-meant words of the first edition with regard to the propagation and defense of the gospel.

It is also known that Calvin called Luther "an apostle," elected by God Himself.

In 1549 Calvin wrote a letter to King Sigismund of Poland wherein he expresses his joy about the progress of the gospel in Poland.

In the same letter he mentioned the name of Johannes a Lasco, a Polish nobleman, who later on played an important role in London and also in Germany. Calvin said, "I foresee that he will transfer the torch of the gospel also to other nations."

In 1561 Calvin wrote in a letter to the Scottish Reformer John Knox, "I rejoice exceedingly, as you may easily suppose that the gospel has made such rapid and happy progress among you."

Finally, in the same year, Calvin wrote a letter to Bullinger about the progress of the gospel and the request for more preachers of God's Word:

It is incredible with what fervent zeal our brethren are urging forward greater progress. Pastors are everywhere asked for from among us with as much eagerness as the priestly functions are made the object of ambition among the Papists. Those who are in quest of them besiege my doors, and pay their court to me as if I held a levee. They vie with one another in pious rivalry, as if the condition of Christ's Kingdom were in a state of undisturbed tranquility. On our part, we desire as much as it lies in our power to comply with their wishes, but our stock of preachers is almost exhausted. We have even been obliged to sweep the workshops of the working classes to find individuals with some tincture of letters and pious doctrine to supply this necessity.

Calvin wrote this letter just three years before his death. One can say, this has to do with the ministry in the congregations, but we may also say: this has to do with the propagation and the progress of the gospel. Calvin was very concerned about that. It is, therefore, absolutely wrong to slate that Calvin lacked the idea of apostolate!

Martin Bucer←⤒🔗

Calvin was closely connected with Martin Bucer, especially in his Strasbourg years, in 1538-1541. It is interesting to know Bucer's ideas about mission. We may say that he expressed himself very clearly about the task of mission. More than Luther and Calvin, Bucer stressed very much that the apostles only made a beginning of the work of mission in their times. He stated that the apostles had indeed received a special calling for the propagation of the gospel in the whole world. But speaking about the apostle Paul, Bucer said that "the apostolic fire was present in him in great measure as an example also for the times to come." He also stressed that the apostles had received extraordinary gifts: prophecy, healing, tongues. But therein, Bucer said, is an indication that "just as the beginning, also later on all the power would be delivered to the church to gather the church of God out of the whole human race." For although these extraordinary gifts were limited to the apostolic era, yet the church would also later on be able to fulfil the calling of Jesus Christ without the miracles of the beginning of the Christian church. Already in his book, dated from 1523 Instruction of Christian Love, Bucer said, "The believer, like a perpetual spring, must pour out the goodness which God imparts to him through Christ by furthering the welfare of all men" (facs. edition, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A./London, England 1980, p. 49).

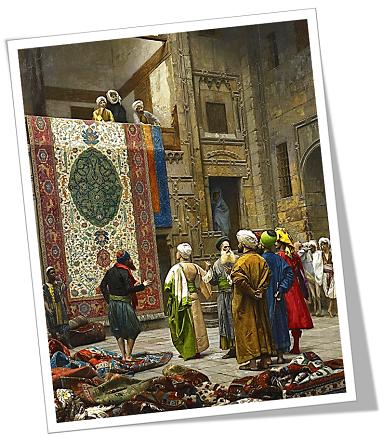

Starting with these ideas, Bucer reproached the rulers that they neglected mission. He said, it is true that desire for expansion drove them into the world, but at the same time they had no desire to win the people for the church and for Christ. The Spaniards hurt the native population in a terrible way and tortured them. "Is that, then, what they call the propagation of Christianity?" he asked. Bucer also paid special attention to the Jews. He wrote, "Exactly through the sinful neglect of mission work among the Jews, now the Jews became usurers in the midst of Christianity." In this respect Bucer also made a comparison with the Turks. He said, "In the same way we can say that the Turkish became violent oppressors of the Christians, and also that newly discovered islands and nations have become a source of much misery for the Christian peoples."

As we saw before, Luther stressed that mission work is the work of God Himself. Bucer agreed with that, but he stressed at the same time that this does not exclude that we as God's people have also a task. As he put it, "There is also a human element in the proclamation of the gospel."

Very important is this statement of Bucer: "Omnis ecclesia Christi debet esse evangelisatrix": each and every church of Christ has to be a mission church, a church that evangelizes.

Conclusion←⤒🔗

There is more to be said about Reformation and Mission. But I think it is very clear now that it is impossible to describe the Reformation times while leaving out the word mission. On the contrary: we may discover great powers which were already present in Reformation times in the hearts of men like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Martin Bucer. Later generations took these powers over and would develop them in obedience to the great commission, given by the King of the church to the church of all ages!

Add new comment