Puritan Christianity: The Puritan Era

Puritan Christianity: The Puritan Era

The Puritan era covers approximately a century and a half, from the 1550s to the 1690s. To put this period in its historical context I have to draw a brief sketch of the English Reformation. That Reformation, unlike the one in the Netherlands and Scotland, was never completed, but ended in a compromise called the Anglican Church. Puritanism, one might say, was born of a compromise or half-way settlement between Roman Catholicism and Calvinism.

The Reformation in England was also different in that it was typically English. By that I mean that despite the obvious influence of Luther and Calvin on its development, the English Reformation was not simply an import from Germany or Geneva. It had its own indigenous character as it grew out of a movement dating all the way back to the fourteenth century. One could say it all started with John Wycliffe (1329-84) who has been called "the morning star of the Reformation."

Wycliffe and his disciples, the Lollards, recognized and protested against Roman Catholic errors and practices long before Luther was born and made his mark on history. Wycliffe, a professor at Oxford University, stated publicly that wealth and political power had so corrupted the church that a radical reform was necessary. The church, he said, should return to the poverty and simplicity of apostolic times. He even called the pope the antichrist. Not the papacy or the church, but the Bible should be the only rule of faith, he declared.

Wycliffe and his disciples, the Lollards, recognized and protested against Roman Catholic errors and practices long before Luther was born and made his mark on history. Wycliffe, a professor at Oxford University, stated publicly that wealth and political power had so corrupted the church that a radical reform was necessary. The church, he said, should return to the poverty and simplicity of apostolic times. He even called the pope the antichrist. Not the papacy or the church, but the Bible should be the only rule of faith, he declared.

The Bible, however, was not accessible to the common people because it was written in Latin; so Wycliffe translated it into the English language. His followers carried his teachings and the newly translated Bible into many parts of England. The Roman Catholic Church, of course, opposed this reform movement and tried everything to silence Wycliffe. But he also had a lot of support from people generally, including some very powerful nobles who protected him so that he did not fall into the hands of his persecutors. As a result, he was able to do much good and died in peace in 1384.

Wycliffe's teachings continued to be spread all over England by the Lollards. The opposition from the side of Rome continued also and became stronger as time went on until at last the bishops succeeded in passing a law which condemned heretics to be burned. Many Lollards perished in the flames, but their teachings could not be destroyed. By the time of the Reformation Lollardism still lingered on in secret and thus the English soil was fertile and ready to receive the seed of the Gospel.

It is not true, therefore, as some historians say, that the English Reformation was largely a political affair, the result of King Henry the VIII's conflict with Rome over the issue of his divorce from his wife, Catharine of Aragon. To be sure, this whole sordid affair played an important role in the development of the English Reformation, but it is incorrect to say that the king's marital problems were the primary cause of the Reformation. The primary cause was the hunger on the part of many Englishmen for the Word of God and the Gospel of grace.

During the early years of the reign of Henry VIII, say from 1511 to 1514, the great Dutch scholar and humanist Erasmus lectured at Cambridge University and made many friends in England. Erasmus had published a new translation of the Greek New Testament and this, as well as other writings of his in which he criticized the Roman church, sparked great interest among scholars everywhere. A few years later, after Luther's bold stand at Wittenberg, his writings were disseminated all over Europe, reaching also England's two universities: Cambridge and Oxford. The result was that many students embraced Lutheran doctrine.

Among them was William Tyndale. Influenced first by Erasmus and then by Luther and Zwingli, he became thoroughly convinced of the truth set forth by these two great Reformers, especially their emphasis on the Word of God being the only norm for faith and life. He realized that the most effective way to promote the cause of the Reformation in England was to make the Bible available to the common people in their own language. There was already a Wycliffe translation, but there were so few copies left, and besides, the English language had undergone so many changes in the course of two centuries, that a new translation was called for.

Tyndale produced and published his new translation in Germany. The year was 1525. It was an excellent translation of the New Testament from the original Greek, not from the Latin Vulgate as Wycliffe's had been. The first edition was 6,000 copies. Seven more editions followed. Next, he translated parts of the Old Testament, all this in the face of fierce persecution. Finally, he was betrayed, arrested and sentenced to death. On October 6, 1536, Tyndale suffered martyrdom near the city of Brussels in Belgium. But his influence continued. His translation of the Bible did much to further the cause of the Reformation in England.

Next we turn to king Henry VIII and his role in the English Reformation. That role was rather complex. In a way, one can say that he furthered the cause of Protestantism in England, but one can also make a case for saying he hindered it. It is certain that he always remained a Catholic and a bitter enemy of the Reformed faith. Henry VIII was well educated and an able lay theologian. He wrote a book against Luther's teachings for which pope Leo X rewarded him with the title of Defender of the Faith.

Next we turn to king Henry VIII and his role in the English Reformation. That role was rather complex. In a way, one can say that he furthered the cause of Protestantism in England, but one can also make a case for saying he hindered it. It is certain that he always remained a Catholic and a bitter enemy of the Reformed faith. Henry VIII was well educated and an able lay theologian. He wrote a book against Luther's teachings for which pope Leo X rewarded him with the title of Defender of the Faith.

Henry VIII is known for his extraordinary love life. He had no fewer than seven wives, not all at the same time, true enough, but successively. It all started with Catharine of Aragon from Spain.

The pope had granted him permission to marry this lady after the death of his brother Arthur, her first husband. As Henry's love for Catharine waned, especially after her failure to give him a living son and heir – two sons died in infancy – he requested another pope to annul the marriage. He argued that the previous pope should never have granted him permission to marry Catharine because Scripture forbids one to marry the wife of a brother (Leviticus 20:21). By doing so, he claimed, he had really never been married to Catharine in any true sense; in fact, he had been living in sin all those years! Henry therefore felt he was free to marry another.

The pope, Clement VII, was not about to grant this request. He did not actually say no to Henry, but he prolonged negotiations as long as he could, never intending to reach a decision favourable to the king. The pope had political reasons for this delay. The Emperor Charles V was Catharine's nephew, and the Pope could not afford to displease him. Charles was the most powerful monarch of his time. So the king of England waited and fumed in vain. Henry wanted to marry Anne Boleyn, a lady-in-waiting at the court, and finally, in desperation, he broke with the pope and the Church. Without papal approval he secured the appointment of Thomas Cranmer as Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer was willing to accept Henry's claim that he had never been married to Catharine according to the law of God and agreed to join Henry and Anne in marriage. The King then declared himself head of the Church of England, persuaded Parliament to pass the Act of Supremacy of 1534, whereby the new arrangement in church and state became law.

Although Henry never became a true Protestant, he did promote the Protestant cause in spite of himself. For instance, he followed the advice of Archbishop Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, his chief minister of state, with respect to making the Bible available to the public. In 1538 the king required a copy of the Scriptures in English to be placed in every parish church in his realm. The churches were to be left open at all convenient hours of the day so that people might have access to the volume. This royal decree is most remarkable and a striking illustration of God answering the prayers of His people. Two years earlier, William Tyndale when dying at the stake, had prayed, "Lord, open the king of England's eyes." This prayer was thus literally fulfilled.

The King also introduced a book of prayers and published the so-called Ten Articles, in which he laid down what doctrines had to be taught in the church of which he now was the head. These doctrinal pronouncements were designed as a compromise between Catholic and Protestant teachings. There were to be three instead of seven sacraments. Images and relics were allowed, but a warning was attached that venerating these things easily leads to superstition. A vague and rather ambiguous statement on justification was included. In a later document issued in 1539, the Six Articles, Henry returned to a more Catholic stance as he insisted on transubstantiation, seven sacraments and celibacy for the clergy.

By 1547 Henry had gone through five wives – divorcing some, beheading others. He got one male heir, Edward, from Jane Seymour who died in childbirth. Only the last wife survived him. His marriages confirmed his extreme egotism and his ability to tailor his conscience to fit his political and personal desires. What reform occurred during his reign was in spite of, rather than because of his actions.

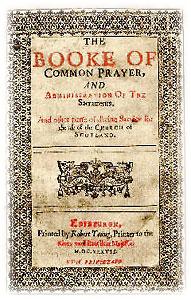

Edward was only nine when his father died. Officially, the boy became king, but England was actually ruled by regents during his short reign. During the six year-long regency the Reformation made rapid progress. Cranmer, who by this time was a genuine Protestant of the Zwinglian persuasion, welcomed Reformers from the Continent, cooperated with the regents in removing images from churches and replaced the Roman Catholic Missal (Service Book) with the English Prayer Book. Actually, two such books were issued, the first in 1549, the second in 1552. The former still retained certain Roman usages, but, as Protestant teaching became more firmly established, it was replaced by the 1552 Book containing 42 Articles of Religion, later reduced to 39 which is still in use in the Church of England today.

Edward was only nine when his father died. Officially, the boy became king, but England was actually ruled by regents during his short reign. During the six year-long regency the Reformation made rapid progress. Cranmer, who by this time was a genuine Protestant of the Zwinglian persuasion, welcomed Reformers from the Continent, cooperated with the regents in removing images from churches and replaced the Roman Catholic Missal (Service Book) with the English Prayer Book. Actually, two such books were issued, the first in 1549, the second in 1552. The former still retained certain Roman usages, but, as Protestant teaching became more firmly established, it was replaced by the 1552 Book containing 42 Articles of Religion, later reduced to 39 which is still in use in the Church of England today.

Edward died in 1553 at the tender age of sixteen. With him died also the Reformation, at least for a time. He was succeeded by his half-sister Mary, the daughter of Catharine, Henry's first wife. She was an ardent Catholic and was resolved to restore the Catholic religion to her realm. Fortunately, her reign too was brief, only five years, but during that short period the Reformation in England suffered a tremendous setback. Beginning with the Act of Repeal (1554) by which papal authority was reimposed, a veritable reign of terror was unleashed upon Protestants of every stripe. This earned her the name Bloody Mary. Three hundred men and women suffered martyrdom. Many Protestants fled to the Continent as "Marian Exiles." Among those put to death by Mary was archbishop Cranmer.

Sad to say, most of the clergy accommodated themselves as easily to Mary as they had to Edward. Later they were to change loyalty again under Elizabeth I.

Elizabeth was Mary's half-sister. She was crowned Queen of England in 1558. During her long reign – she died in 1603 – Protestantism became the established religion of the realm. It was a form of Protestantism that dearly bore the mark of compromise. The Anglican Church that emerged under her supervision was and always remained a middle way between Roman Catholicism and Reformed Protestantism.

When Elizabeth came to the throne all Protestants rejoiced, but none were more hopeful than the true Protestants, who like Cranmer and Tyndale, longed for a thoroughly Reformed Church, conform in every way to the New Testament model in doctrine, worship and practice. Soon after her accession, in 1559, Elizabeth passed a New Supremacy Act whereby for the second time and now for good, the government rejected all authority of the pope over the Church of England. Next, she reintroduced the Second Prayer Book of Edward VI. She also, in 1563, adopted the Thirty-Nine Articles, a moderate but basically Protestant, even Calvinistic formulation of Anglican belief. These she made normative for the church. Any dissenting clergy were immediately removed from office.

Elizabeth's brand of Protestantism aroused intense opposition from Roman Catholics. In 1570 the pope excommunicated her and urged her subjects to rebel. He sent Jesuits into England to convert people to Catholicism and foment discontent. Philip II, Bloody Mary's husband, dispatched a great Armada of battleships, hoping to invade and conquer England, but a fierce storm off the coast of England destroyed most of the ships.

In response to this dangerous opposition, Elizabeth tightened restrictions on English Catholics. While permitting them private worship in their homes, she dealt decisively with all treasonous activity, executing some 220 traitors during her forty-five year reign.

In many ways she was a wise and benevolent queen. Yet many Protestants in her realm were unhappy with her because they felt that she had not gone far enough in reforming the English church. Here's where the Puritans enter the stage of history. The Puritans, as they were called when they started to make a noise, had been influenced by continental Calvinism. Especially after the Marian exiles returned, they were impressed by what they had seen in such places as Geneva, Strasbourg and Frankfurt, where the Reformed churches had been organized according to the prescriptions of Scripture. All the errors and abuses of Roman Catholicism had been removed and the pure worship of God had been restored.

These Puritans, therefore, sought a similar Reformation in their own country. They wished to purify the Church of England from within, removing the vestiges of Catholicism such as ministerial vestments, form prayers and episcopal church government. They wanted to simplify the worship and make their church a Presbyterian body comparable to the Reformed church in Geneva and other places.

Elizabeth, however, would have none of this. She believed that for the peace of the church and the nation she must resist what she felt was dogmatism and extremism of the Puritans just as she was resisting that of the Catholics.

Elizabeth died in 1603 and was succeeded by James I who was king of Scotland. Under his reign and that of his son Charles I, the Puritans became a strong force in English society until by 1640 they took up arms against their monarch.

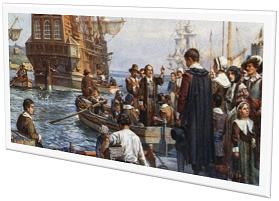

James was a royal absolutist. He believed in the divine right of kings and insisted that he was responsible to God alone and not in any way accountable to the people, not even to the Parliament. To make matters worse, James carried on a campaign against the Puritans, insisting that he would make them conform or else drive them out of England. He was convinced that a Church of England organized along Calvinistic or Presbyterian lines would prove uncontrollable. As a result of his campaign, many Puritan clergy lost their pastorates. Many others left the country, some going to Holland and later to America, and others going directly to the new World. Much to James' surprise, however, the Puritan cause gained widespread support. Many members of Parliament, especially the business classes, were outraged by the king's behaviour and in reaction refused to vote James the funds he needed for his many extravagant activities. Puritans and non-Puritans alike joined in stiff resistance to James' divine-right monarchy.

James was a royal absolutist. He believed in the divine right of kings and insisted that he was responsible to God alone and not in any way accountable to the people, not even to the Parliament. To make matters worse, James carried on a campaign against the Puritans, insisting that he would make them conform or else drive them out of England. He was convinced that a Church of England organized along Calvinistic or Presbyterian lines would prove uncontrollable. As a result of his campaign, many Puritan clergy lost their pastorates. Many others left the country, some going to Holland and later to America, and others going directly to the new World. Much to James' surprise, however, the Puritan cause gained widespread support. Many members of Parliament, especially the business classes, were outraged by the king's behaviour and in reaction refused to vote James the funds he needed for his many extravagant activities. Puritans and non-Puritans alike joined in stiff resistance to James' divine-right monarchy.

James' son, Charles I, continued his father's policies against the Puritans and harassed them even more. His actions also only increased popular opposition to the monarchy. Then in an act of utter foolishness, Charles who was also king of Scotland and archbishop Laud, attempted to force the Anglican Prayer Book on the Scottish Presbyterians – leading those hearty Calvinists to rebel and support the Puritan party in England. This ill-thought-out religious policy, combined with Charles' effort to rule England without parliament, led to an explosion. When Charles, desperate for cash, was finally forced to call for Parliament, he discovered he had a full-scale rebellion on his hands, a rebellion in which Puritans and other opponents were able to defeat Charles and finally have him beheaded.

This left the way open for the Puritans. The Puritan parliament met little resistance as they set about abolishing the episcopacy in England and reconstructing the church along presbyterian lines. Charles' policies had been too unpopular. To effect this further reform the Westminster Assembly of divines (1643-49) was convened. It produced the basic documents of presbyterianism: the Westminster Confession of Faith with the Larger and Shorter Catechisms.

Ironically, at just this point the English general and independent Puritan, Oliver Cromwell (1559-1658) gained control and rejected a state-enforced Presbyterian church. Instead, he proposed toleration for a variety of Puritan churches while imposing restrictions on Anglicans and Catholics. Cromwell's view was supported by many who feared that a state Presbyterian church would prove as intolerant as the Anglican establishment had been.

After Cromwell's death the English people, weary of the religious unrest and Cromwell's attempts to regulate morality, returned to the monarchy. When Charles II took the throne, the Anglican church was re-established as the Church of England. During and following this period of the restoration, Puritanism lost much of its influence, especially after the Great Ejection in 1662 when 2,000 Puritan pastors were evicted from their pastorates because they refused to conform to Anglican establishment religious policies.

After Cromwell's death the English people, weary of the religious unrest and Cromwell's attempts to regulate morality, returned to the monarchy. When Charles II took the throne, the Anglican church was re-established as the Church of England. During and following this period of the restoration, Puritanism lost much of its influence, especially after the Great Ejection in 1662 when 2,000 Puritan pastors were evicted from their pastorates because they refused to conform to Anglican establishment religious policies.

Puritanism resurfaced in a different form and to varying degrees in the Evangelical revivals under Wesley and Whitefield. In America, however, Puritanism lived on as a strong force in society until well into the eighteenth century and beyond. Puritan theology, however, never died out and never will. In the nineteenth century men like Bishop Ryle, an Anglican and C.H. Spurgeon, a Baptist, and more recently Dr. D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones, were modern Puritans. At the present time there are still many preachers and congregations which follow a basically Puritan approach to faith and life.

Add new comment