Kingdom of God or Justification of the Sinner? Paul between Jesus and Luther

Kingdom of God or Justification of the Sinner? Paul between Jesus and Luther

The message of both John the Baptist and Jesus was about the Kingdom of God. Not only did they frequently use the terminology of the Kingdom from the very beginning, but others also use this same terminology to characterize and summarize the preaching of the Lord and his forerunner.

1. Introduction⤒🔗

Paul seems to be an exception. Is he not the apostle of the justification of sinners, first the Jew and also the Greek? What clearly forms the centre in the Gospels seems to be marginalised in Paul’s Epistles.

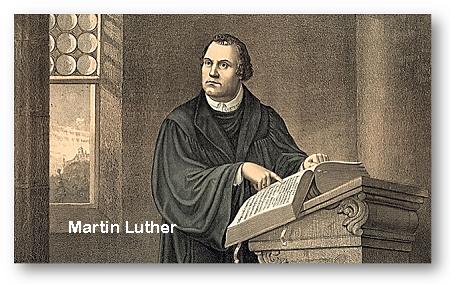

So it is natural and not surprising that Luther found his personal way to paradise especially through Paul. There is a direct connection between the apostle of the nations – the preacher of justification – and the German reformer of justification by faith alone.

But what about the apparent discontinuity between Paul and Jesus? Is there a contrast between the message of the kingdom for this world and the preaching of justification of sinners? Or do we read Paul through the eyes of Luther instead of through the gospel of Jesus, and are we thereby creating a discontinuity that in reality did not exist? Is the discontinuity not between Paul and Jesus but rather between Luther and Paul?

2. Recent moves←⤒🔗

2.1 Discontinuity between Luther and Paul or between Paul and Jesus?←↰⤒🔗

The latter possibility has been defended by different admirers of the so-called new Paul paradigm. Kingdom of God or Justification of the Sinner? Paul between Jesus and LutherThey claim that we have misunderstood the apostle for more than four centuries and that we have to de-Lutherize St. Paul and to view him again within the structure of Judaism in order to also re-unite him with Jesus, teacher in Israel.

The more we disconnect Luther and Paul, the more we seem to get an opportunity to bridge the gap between Paul and Jesus that was discussed for more than two centuries in the old Paul paradigm. Many theologians in the 19th and 20th century have drawn the picture of a Jewish Jesus and a Hellenised Paul: in fact, they claim that Paul should be considered the real betrayer of the original gospel, who built a non-Jewish Christology out of the simple, Jewish message of the kingdom of God, the kingdom of love, as we find it in the preaching and life of Jesus.

2.2 Back to Jesus to find the kingdom?←↰⤒🔗

In the 20th century this view on Paul and Jesus had to retreat for a certain period under the influence of the anti-liberal theology of Karl Barth. But at the end of the 20th century this view on Jesus as a simple and original teacher regained its old influence. Many theologians returned to the denial of the atoning power of Jesus’ death and to the reduction of Jesus to a Jewish prophet. As a result, the kernel of the Gospel is at the same time no longer atonement but the Kingdom of God.1

The renewal of an old dilemma (Kingdom or atonement) became very visible in a couple of Dutch lectures published in the series “Leidse lezingen.” The translated title is Atonement or Kingdom: about the priority in preaching the gospel (Van den Brom et al., 1998). In this publication we find an article entitled “Eerherstel voor het koninkrijk” (Rehabilitation of the kingdom), in which De Jonge defends the priority in preaching of what Jesus taught about the kingdom of God.2 The person of the Christ, belonging to later dogmatics, disappears behind the doctrine of the human Jesus about the heavenly kingdom. This theme should be far more important than the theme of the atonement that has been popular since the Reformation.

If the message of God’s coming kingdom and men’s obligation to obey should be the central theme in preaching and theology, other themes will have to give up their central place and become less important. This goes particularly for the theme of atonement. It does not mean that this theme should be banished, but that it is of secondary importance.3

2.3 The New Paradigm in Pauline Studies (Dunn)←↰⤒🔗

Whenever there is a shift in opinion about the centre of Jesus’ message, Paul becomes involved. The move is made from atonement to kingdom, and at that moment Paul becomes a solitary pawn in the centre of the chessboard. The next moves are made with this advance pawn, not only in the old Paul-paradigm, where he is taken from the board, but also in the new Paul-paradigm, where he is moved away from Luther and pushed in the direction of the Jewish Jesus, the prophet of the kingdom.

The issue at stake is whether there is a discontinuity between the gospel of the universal kingdom and the message of the individual justification of the sinner. In other words: did the original message of a New World disappear behind the later Christology and soteriology aimed at individuals? Is a return to the message of the Kingdom in fact the same as the archaeology of the original message of God, which through the centuries has gradually been buried under the dust of personal theology?

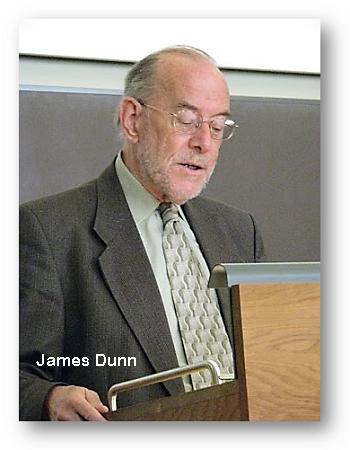

I take my starting-point in the publications of James D.G. Dunn, because he is the best-known spokesman of the new paradigm among theologians and preachers.4 In particular, Dunn speaks about the interpretation of the Law as the point of misunderstanding between Luther and Paul. This point, however, is connected with our issue of the kingdom. This becomes apparent in a relatively small publication entitled The Justice of God: A Fresh Look at the Old Doctrine of Justification by Faith (Dunn, 1993).

In this publication, written in cooperation with Alan M. Suggate, Dunn stresses the point that Luther has individualized the Hebrew social concept of righteousness. As soon as we see the concept of righteousness not as something individual but as something social, ethnic, universal, it comes very close to the concept of the Kingdom of God. The ‘justice of the Kingdom’ is the non-individual justice of God in society. The second part of the book contains case-studies about this ‘justice of the Kingdom’ by Suggate. The discussion involves secular issues: Germany (the doctrine of the two reigns), Japan (the mission of the emperor), and England (free market and faith).

The more the justice of the Kingdom is painted in the colours of society, the more the personal justification of the sinner through the sacrifice of Christ is marginalised. Dunn acknowledges the existence of this margin, but at the same time he accepts that it is not so clear exactly where the margin lies: it is a matter of dispute. In his opinion, this is not a great problem because it does not belong to the central issues of Paul’s theology (p.9): “in Christian thinking ‘justification by faith’ is closely tied-in to belief about Jesus’ death on the cross. The teaching of Paul is that Jesus’ death somehow makes satisfaction before God for the sin of others. (…) But how this comes about has been a matter of dispute between Christians. Was Jesus’ death a sacrifice? (…) But how did that make the difference for God? Did Jesus somehow become a substitute for others in his death?”

Dunn asks many questions here: does not this apply the law-court metaphor too rigidly? And: how is this sacrifice repeated in the Eucharist? And: do we have to speak about gratia infusa or gratia imputata – grace infused or grace imputed? In reaction to all those questions Dunn says (p.10):

Fortunately such disputes have been largely overcome, with each side recognizing the importance of the emphasis made by the other. Important as they are, we need not go into them furtherhere. If readers so desire they can pursue them further in the reading suggested at the end.

Thus Dunn, in fact, minimalizes the importance of the atonement language because of too many uncertainties.

With Dunn as representative for the new Paul-paradigm, Paul is not only de-Lutherized, but the whole Gospel is de-Christologized on behalf of the supremacy of the Spirit of the Almighty. In fact, the Justice of the Kingdom is the Spirit of the Kingdom (see Dunn, 1998:190-191).

3. Discussion←⤒🔗

3.1 Jesus and the Kingdom←↰⤒🔗

The pattern of Jesus’ life←↰⤒🔗

In the Gospels we experience a remarkable development. Jesus starts with the preaching of the Kingdom, which is broad and world-wide in scope. The unlimited importance of this theme is demonstrated by many, many healings and by the expulsion of demons from the human world. Really signs of a divine Kingdom! (see Van Bruggen, 1993: chapter 3).

But further on in the Gospels, the miracles seem to become less important. More and more we hear about suffering. Many distance themselves from Jesus. And finally his life ends in loneliness, prison, and death. Is this the tragedy of a world reformer? No, because Jesus himself frequently makes clear that He has chosen this way. The preacher of the Kingdom prefers the road to the hill of the cross in the desert. That is his incomprehensible strategy!

Frequently Jesus speaks about “my hour”: the hour of his suffering, death, resurrection, and glorification. That hour has the splendour of the Kingdom of glory, but it points to Gethsemane.

Just in the last minutes before that hour, Jesus breaks the bread: “This is my body for you: remember Me!” Even the diehards among critics have to acknowledge that Jesus instituted something like the Lord’s Supper, because we cannot find any explanation for this ceremony outside of the historical Jesus.

However, when Jesus’ life on earth shows a direct connection between the Conqueror of the Demons and the Dying Prophet, it becomes very difficult to separate the message of the Kingdom from the Day of universal atonement.

The sequel after Easter←↰⤒🔗

Such a separation is all the more impossible because the perspective of the Kingdom is still fully present after Jesus’ death. His death is followed by his glorious resurrection: the conqueror of the demons is also the conqueror of death! And his ascension makes it clear that he is no longer bound by the gravity of the earth that separates mankind from the angels. The ascension is accompanied by the promise of the restoration of all things! And in the book of Acts we hear again about healings and exorcisms. All this shows that we did not lose track of the Kingdom on the way to the cross: on the contrary!

The atonement through sacrifice is the last remedy in this world of sinners and death to restore the lost Kingdom of heaven. There is no discrepancy between Kingdom and justification in the life of Jesus. His remarkable way of living and dying can be understood as soon as we acknowledge that the Kingdom of God has to return in a world that has closed its doors to God in enmity against God Himself.

Fragmenting the Gospels←↰⤒🔗

The view of the separation between Atonement and Kingdom, so commonly held today, is only possible at a great price. This price is that we have to deny the gospel as history and as a message presented through facts. If we reduce the gospels of the apostles and eyewitnesses to a loose collection of separate words of Jesus, connected by a fictional framework of stories, we create an unbridgeable abyss between the prophet and the king, between the teacher and the leader. This is the regrettable illness of modern biblical scholarship in the Western world. History is exchanged for stories, facts disappear behind legends of the ancient church community. Apparently you can focus on the potsherds while missing the beauty and design of the original, undamaged pottery!

In summary, Jesus’ preaching about the Kingdom of heaven, in combination with his life on earth, makes it impossible to view such topics as his life, his person, and his task as belonging to a secondary Christology, added later by the Christian community to the original, simple teaching of Jesus about the Kingdom of God. The way in which he speaks about this Kingdom – against the background of John’s preaching and with the authority of a judge – places his own person and his work at the very centre of attention.

3.2 Paul and the Kingdom of God←↰⤒🔗

To determine the central message of Paul, we must look at his sermons in Acts and the broader background of his epistles, since on the surface his Epistles are far too limited to special situations and specific problems to extrapolate from them the fundamentals of his preaching.

When we analyze his sermons and the supposed background and foundation of his letters, we find also in Paul (as in the other apostles) the close connection between the expectation of the Kingdom of God and the Person of Jesus Christ.

Preaching in the Diaspora←↰⤒🔗

In Acts, “preaching the Kingdom” is a way of characterizing apostolic preaching in general (Acts 8:12; 14:22; 19:8; 20:25; 28:23). Although in the epistles we regularly find allusions to the preaching of the Kingdom (1 Thess. 2:12; 1 Cor. 4:20; Gal. 5:21; 2 Pet. 1:11; James 2:5, etc.), the frequency with which the Kingdom is mentioned drops sharply. In its place the expression preaching Christ or preaching the gospel gains prominence.

This would seem to be a shift in emphasis from an expected reality to a revered person. But this apparent shift becomes more understandable in light of the way in which Jesus taught the secrets of the Kingdom of heaven (cf. Feine, 1919). The formulation of his message was aimed at his immediate context: Jews under the spell of the Baptist. What he taught about himself is therefore also often expressed in the terminology of the coming Kingdom.

But in the Diaspora this specific context (Jews under the spell of the Baptist) did not exist. For this reason the horizon, the expected Kingdom of heaven, is still present in Acts and the epistles, but the path to the Kingdom (Christ) is preached more directly and now receives all attention as the trajectory of faith immediately before us.

Kingdom and King←↰⤒🔗

Paul and Peter view the Kingdom of God as the new order that will become a reality on earth when Christ appears. The nearness of this Kingdom thus becomes the nearness of the Lord (Phil. 4:5; Rev. 22:12). Faith in Christ, and justification with sanctification as the way to enter the Kingdom, now become the framework within which the dynamic equivalence of what Jesus taught about the smallness of the Kingdom, its simplicity, and so forth, is presented. And the reality of the connection between faith and the coming Kingdom now becomes apparent in the first gift, the Holy Spirit.

When Paul says that God has “brought us into the Kingdom of the Son he loves” (Col. 1:13), he does not mean that this Kingdom is the Christian community. Rather, he is speaking about the indissoluble tie that already exists with the Kingdom of heaven. Thus he also says with regard to people who are still living on earth: “God raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms in Christ Jesus” (Eph. 2:6). At the same time, the assurance of faith of the people who know that they are already citizens of that Kingdom through the Spirit, and who, through this Spirit, already share in its first gifts, does not rule out the fact that entering into this Kingdom is still future, so that Paul can write, “The Lord will rescue me from every evil attack and will bring me safely to his heavenly Kingdom” (2 Tim. 4:18).

The fact that the terminology of “the Kingdom of God” is not central in the later development of the teaching of the church is thus consistent with the flow of history. The early church and the Reformation church clearly understood the striking way in which Jesus dealt with the concept of the Kingdom of God when they placed the propitiation by means of Jesus’ atoning death and the salvation through God’s only Son at the centre. Today the gospel of the Kingdom of God consists in bestowing the power of faith in Christ. This faith preserves us and is the means by which we inherit the future. The Spirit of God, who already lives in all believers, is the pledge of the promised inheritance, for which we now pray with confidence: “Thy Kingdom come.”

3.3 Luther, Dunn, and Paul←↰⤒🔗

Did Luther misunderstand Paul and have the churches of the Reformation under his influence lost the social concept of the Kingdom and only preserved the individual and soteriological concept of justification? This is a common accusation, also found in Dunn’s writings. At this point we have to face three questions:

- Who is the real Luther?

- Who is the real Dunn?

- Who is the real Paul?

Who is the real Luther?←↰⤒🔗

Luther is charged with changing the focus from objective righteousness to individual, subjective righteousness, with the effect that the salvation of the individual soul suppressed the justice of the Kingdom of God. All this was the result of Luther’s wrong view of the law, of the Jews, and therefore of Paul (see Dunn, 1993).5

Is this really Luther? In fact, Luther is not so one-sided. In the preface to the first volume of his collected Latin works he tells us how he gradually came to his specific conviction. He acknowledges that he was influenced by the writing and teaching of Augustine (Weimarer Ausgabe 54, 186, 25-29). Romans 1:17 became decisive for him in this process. He stumbled over the expression ‘God’s righteousness’ because he interpreted it as God’s righteousness in punishment (iustitia formalis seu activa) (Weimarer Ausgabe 54, 185, 17-20). Gradually, however, God showed him the connection of Romans 1:17a with 1:17b (“the righteous shall live through faith”). So Luther concluded that Paul was writing about Gods righteousness by which we are justified (iustitia Dei passiva). Luther felt himself reborn (renatus) and walked through an open door into paradise (Weimarer Ausgabe 54, 186, 3-9). From this perspective he started to read the Psalms and the whole Bible. And to his relief he found Augustine on his side.

What happened with Luther was not primarily an exegetical discovery, since throughout the centuries there have always been two ways of interpreting God’s righteousness in Romans (see Schelkle, 1956). The history of interpretation shows that you can defend either the active or passive interpretation of dikaiosunè and at the same time make no connection at all with the punishment of an angry God.6 What happened to Luther was very personal. As a person Luther had to freed from a distorted image of God, a distortion that for him had become integrated with the active interpretation of the word dikaiosunè. When Romans 1:17 became the door of paradise for Luther (porta paradisi), we see above that door the word “private”: the connection between Romans 1:17a and 1:17b was very personal indeed.

Luther’s change was at the level of the retributive justice of God and not at the level of the restorative justice of God. He did not deny restorative justice, but he focused on retributive justice because he had had a personal problem on that point. As a result, Luther distorted some words of Paul a little, but we cannot say that Luther as a Christian and as a preacher limited the justice of God in an unsocial way to individual salvation. Luther was fully aware of the social justice of God, as is made clear by his reinterpretation of the fourth petition in the Lord’s prayer after the Peasant’s War. In his shorter Catechism he changed the interpretation into a very worldly one about government, neighbours, bread, and society.7

Protestant Christianity in later times sometimes narrowed itself to the individualism of pietism, while interest in this world, politics, and environment diminished. For that development Luther cannot be blamed, however. For him the doctrine of the Kingdom fits with the doctrine of justification, just as access to the palace is possible only by means of the proper key.

Who is the real Dunn?←↰⤒🔗

Luther struggled with the justification of the sinner, but Dunn and others today are wrestling with the justification of the Jews. In fact, this is a crossover. Dunn and others follow the work of Moore and accept that Judaism was not as legalistic and casuistic and as nationalistic as the Reformers thought. And indeed, we have to acknowledge that Luther, Calvin, and others have painted the Jews with the colours of Roman-Catholicism: the Sanhedrin became the counterpart of the pope and his cardinals, and the Roman doctrine of earning merits by good works became the starting point for interpreting what Paul wrote about works of the law.

In the 19th century, the religion of the Jews was seen as a distortion of the original Israelite prophetic religion. So Jesus and Paul were in fact viewed as non-Jews returning to the original religion of Abraham. More than once an anti-Semitic flavour can be tasted in these theories: the Christians are the true successors of Israel, while the Jews are traitors to their religion! It is a good thing that we are liberated from these distorted views of Judaism. More and more we see how multi-faceted Judaism was in the first century. Jesus did not come to destroy Judaism (whatever it may have been), but to destroy the works of Satan in the Jewish world.

Repainting the colours of Luther’s interpretation of Paul does not, however, mean that we have to abandon his painting of God’s justification through faith in the atonement by Jesus Christ. Yet this is precisely what happens with Dunn and most of the defenders of the New Perspective of Paul. Christ as the Son of God disappears and becomes a true son of the repainted Israel. The atonement disappears behind a religious social prophet. This would seem to be the unavoidable consequence of the new paradigm of Judaism. In fact, however, it is the result of a quite different movement made at the same time, but unconnected with the repainting of Judaism. When Dunn no longer maintains the central importance of the atonement in Paul, it is not due to the detachment of Paul from Luther at the level of our understanding of the nature of Judaism. The centre of Luther’s conviction is not built on his ideas about Jews but on his reading of the Gospels. In the same way, Dunn’s detachment of Jesus and Paul from the doctrine of the atonement is not really connected with his understanding of the nature of Judaism. The centre of Dunn’s conviction is built upon his deconstruction of the Gospels and changing them into patches of original words of Jesus in a largely fictional setting. So in fact the new Paul-paradigm is partly Gospel criticism in disguise!

This statement is supported by reading Dunn’s works as a whole. His works show a critical consistency. Already a short sketch of his earlier publications can illustrate this. There is one consistent theological line: the centre is no longer Christ but the Spirit, and the fundamental thing is no longer history and revelation, but experience.

In 1970 Dunn wrote Baptism in the Holy Spirit. He summarizes the results in four sentences that show how decisive the Spirit is for faith:

1. Faith demands baptism as its expression;

2. baptism demands faith for its validity.

3. The gift of the Spirit presupposes faith as its condition;

4. Faith is shown to be genuine only by the gift of the Spirit.Dunn, 1970: 228

Dunn’s next book is entitled Jesus and the Spirit. A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament (1975). In this book he argues that the experience of the Spirit is not the same as accepting revelation. Jesus himself was moved by the experience of God the Spirit.

Dunn writes:

Their theology was produced out of the living dialectic between the religious experience of the present and the definitive revelation of the past (the Christ event), with neither being permitted to dictate the other, and neither being allowed to escape from the searching questions posed by the other – an unceasing process of interpretation and reinterpretation.Dunn, 1975: 361

Inevitably, Dunn’s third book has to deal with Christology: Does Christ disappear behind the Spirit? The title is Christology in the Making (1980). To our surprise the orthodox doctrine of incarnation is exchanged for the modern, humanistic theology of Jesus as the centre point of humanity: God shows how human He really is! In substance, the confession of the Trinity means that God in Jesus Christ has proved himself to be self-communicating love and that as such he is permanently among us in the Holy Spirit (Dunn, 1980: 268).

It is then no surprise that in his Theology of Paul (Dunn, 1998) Dunn reduces the language of Paul about the death, resurrection, and return of Jesus Christ to metaphorical language. Jesus’ statements are not dogmatic or objective; rather, they are the working out of the Christian experience of the Spirit. It is mostly about real experience but not about facts. At the same time, Dunn speaks more about the unity of God than about the divine nature of Christ or the Trinity.

In fact, Dunn makes a separation between Jesus the King and the Kingdom. For Dunn the Kingdom of God is the Kingdom of the Spirit, preached by Jesus and Paul. His de-christologizing of the Kingdom is destructive for the doctrine of the justification of the sinner. It is, however, also destructive for the doctrine of the Kingdom of God. This new approach results in horizontal activism in the name of the Kingdom of God but without a King of salvation.

Who is the real Paul?←↰⤒🔗

Paul’s doctrine about the Justification of the Sinner seems connected with his negative attitude toward ‘works’, and this seems to have a negative effect upon the promotion of the Justice of the Kingdom. In fact, Paul only speaks about this issue in two of his thirteen letters: Galatians and Romans. In both of them he is arguing with non-Jewish readers. He is warning them not to return to ‘works’. But how could they return to works? They had never been Jews under the Law at all!

It is a current idea that ‘works’ is a specific concept of the Law and the Jews. This is not true, however. Josephus never discusses Judaism in terms of works. And modern study of Judaism and Paul has made clear that Judaism was not nomistic or legalistic. In fact, the non-Jewish religions were! The Gentiles tried to deserve the grace of the gods. Seen from the Gentile point of view, the Jews similarly perform good works for their god, and this is why some Gentile Christians feel themselves invited to share the Jewish way of working for their god. At this point Paul enters the discussion. Using the Gentile view of religion and their idea about the religion of the mosaic law, Paul makes it clear that they are mistaken. The religion of Abraham is a religion of faith and not of works and merits. The religion of the Lord of Abraham is quite different from the way they perceive it. Therefore, having returned to the obedience towards the Creator and having received faith in Jesus the Messiah, why return to something that seems similar to their original Gentile way of serving the gods - through works? (cf. Van Bruggen, 2001).

At the level of religion (the attitude towards the Creator) works are a Gentile misunderstanding. A quite different thing is the human attitude and way of life in this created world. On that point Paul shows us the way. The children of the heavenly Kingdom have their responsibility on earth, because the earth is the Lord’s!

4. Conclusions←⤒🔗

4.1 The Scriptures and History←↰⤒🔗

In order to avoid misinterpretations, we must read the texts in the Bible in their historical context as the most natural frame of reference. The Bible is not a textbook about Kingdom or justification, made for quick and simplistic conclusions. The Bible contains documents that are embedded in a history. On the one hand this makes them more limited and specific as texts, on the other hand it gives them roots in the wider context of Gods history with this world. Let me illustrate this with two remarks, one more hermeneutical, the other more theological.

- It is hermeneutically necessary to distinguish between the dominant ideas of the apostles (mostly in the background behind their epistles) and their specific and limited advice in epistles to individual persons and churches.

- The theological dialectic of the ‘already’ and ‘not yet’ of the Kingdom needs revision. We should speak about a partial ‘already’ (in heaven and through the Gift of the Spirit) and a partial ‘not yet’ (as far as the Devil and death have still influence and power for a certain time). We are already justified through faith in the King, but we have not yet entered the Kingdom itself, although we have received the ‘advance or first installment’ of the Spirit.

4.2 Faith and World←↰⤒🔗

To avoid the extremes of individualistic pietism and religious-social activism, it is necessary to carefully describe the connection between and interrelation of God’s Kingdom and the justification of the sinner. They are related as key and palace. You cannot enter without the key and the key allows entry into the world of the King!

Churches of Reformed conviction have two connected tasks in their preaching: to preach the gospel of grace for the sinner, and to make clear how this grace opens the way to worldly responsibility at a social, political, and environmental level.

It is important that the social, political, and environmental responsibility of the children of the Kingdom remains connected with their faith in Jesus Christ in order to prevent humanistic idealism and lack of fervent hope and strong prayer. We should pray “Thy Kingdom come!” and at the same we tremble and humbly ask: “Forgive us our trespasses!”

Bibliography

- Baarlink, H. 1998. Het evangelie van de verzoening. Kampen: Kok.

- De Jonge, H.J.J. 1998a. Eerherstel voor het koninkrijk. In: Van den Brom, L.J. e.a. 1998, pp. 9-20.

- De Jonge, H.J.J. 1998b. De plaats van de verzoening in de vroegchristelijke theologie. In: Van den Brom, L.J. e.a., pp.63-90.

- Den Heyer, C. J. 1997. Verzoening: bijbelse notities bij een omstreden thema. Kampen: Kok.

- Dunn, James D.G. 1970. Baptism in the Holy Spirit. A Re-examination of the New Testament Teaching on the Gift of the Spirit in relation to Pentecostalism. Studies in Biblical Theology 2, 15. London: SCM.

- Dunn, James D.G. 1975. Jesus and the Spirit. A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament. London: SCM.

- Dunn, James D.G. 1980. Christology in the Making. An New Testament Inquiry into the Origins of the Doctrine of the Incarnation. London: SCM.

- Dunn, James D.G.; Alan M. Suggate 1993. The Justice of God: A Fresh Look at the Old Doctrine of Justification by Faith. Carlisle: Paternoster.

- Dunn, James D.G. 1998. The Theology of Paul the Apostle. Edinburgh: Clark.

- Dunn, James D.G. 2005. The New Perspective on Paul. Collected Essays. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 185. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Elsinga (ed.), C.B. 1998. Om het hart van het evangelie. Een boek voor de gemeente over de verzoening. (No place mentioned:) Uitgeverij CeGe boek.

- Feine, P. 1919. Theologie des Neuen Testaments. 3d ed. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

- Hoek, J. 1998. Verzoening, daar draait het Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum.

- Schelkle, K.H. 1956. Paulus, Lehrer der Väter: die altkirchliche Auslegung von Römer 1-11. Düsseldorf: Patmos.

- Van Bruggen, Jakob. 1999. Jesus the Son of God: The Gospel Narratives as Message. Grand Rapids: Baker.

- Van Bruggen, Jakob. 2001. “Kingdom of God or Justification of the Sinner?” In die Skriflig 35 (2001): 253-267.

- Van Bruggen, Jakob. 2005. Paul: Pioneer for Israel’s Messiah. Phillipsburg: P. & R.

- Van den Brom, L.J. e.a. 1998. Verzoening of Koninkrijk. Over de prioriteit in de verkondiging. Leidse lezingen. (Nijkerk/Kampen:) Callenbach.

- Wentsel, B. 1991. God en mens verzoend: incarnatie, verzoening, koninkrijk van God, Dogmatiek Vol. 3b. Kampen: Kok.

Add new comment