The Degradation of Work in Modern Society

The Degradation of Work in Modern Society

The fact that so many people today do not find happiness and blessing in their work would surely suggest that something drastic has gone wrong with work in God's modern world. Why do so many workers today look upon their work simply as a job which they must hold down in order to make ends meet? Why do millions of workers regard such "jobs" as a necessary evil and as "labor in vain" and spend most of their time at work looking at the clock which will tell them when another "shift" is over? Why has work become devaluated and the workers depersonalized?

The answer surely is that the great majority of workers are no longer able to find any meaning in their work. For the great majority of workers today work has lost its meaning, because it has become divorced from the service of Jesus Christ and their own personal lives and from life in the Body of Christ. Above all, work in modern society has lost its meaning because modern post-Christian society has been living for the past four hundred years upon a doctrine of man in society which conflicts with the true nature of reality as revealed in the Word of God. In spite of greatly improved working conditions, high wages, and many other incentives, e.g., health and pension schemes, a growing number of British and American and Canadian workers do not feel they are doing something really worthwhile and of any real importance to their communities. And how could they as long as work is estimated in terms of the profits it brings to the shareholders rather than by the worth of the thing that is made? What sense is there in making ladies' stockings that are worn only once and then thrown away? What pride can the Ford or General Motors employee take in producing an automobile with the latest engine design and body streamlining which he knows will be thrown on the scrap heap within five years? What sense can farmers find in producing butter, wheat, and other grains, which will be stored by their governments because to distribute it does not pay? Just think of all the senseless things which are manufactured today! The enormous quantities of newsprint that litter our streets, the scattered hairpins and smashed crockery, and the knick-knacks of steel, wood, rubber, glass, and tin that we buy at Woolworth's and the other chain stores and then forget as soon as we have bought them.

The answer surely is that the great majority of workers are no longer able to find any meaning in their work. For the great majority of workers today work has lost its meaning, because it has become divorced from the service of Jesus Christ and their own personal lives and from life in the Body of Christ. Above all, work in modern society has lost its meaning because modern post-Christian society has been living for the past four hundred years upon a doctrine of man in society which conflicts with the true nature of reality as revealed in the Word of God. In spite of greatly improved working conditions, high wages, and many other incentives, e.g., health and pension schemes, a growing number of British and American and Canadian workers do not feel they are doing something really worthwhile and of any real importance to their communities. And how could they as long as work is estimated in terms of the profits it brings to the shareholders rather than by the worth of the thing that is made? What sense is there in making ladies' stockings that are worn only once and then thrown away? What pride can the Ford or General Motors employee take in producing an automobile with the latest engine design and body streamlining which he knows will be thrown on the scrap heap within five years? What sense can farmers find in producing butter, wheat, and other grains, which will be stored by their governments because to distribute it does not pay? Just think of all the senseless things which are manufactured today! The enormous quantities of newsprint that litter our streets, the scattered hairpins and smashed crockery, and the knick-knacks of steel, wood, rubber, glass, and tin that we buy at Woolworth's and the other chain stores and then forget as soon as we have bought them.

Think of the advertisements imploring us, exhorting us, cajoling us, menacing us, and bullying us to glut ourselves with things we do not really need, in the name of snobbery, slothfulness, and sex-appeal. The advertisements are full of the Ponce de Leon appeal; every day they promote the sale of soap, toothpaste, breakfast cereals, cosmetics, and ladies' lingerie on the specious grounds that they can restore the glow and vigor of eternal youth. As long as gullible people continue to believe such rubbish so long shall we hear and read such things as "Go sweet, go fresh faced, go young, go angel face." The fountain of eternal youth is not to be found in some nationally promoted product as the advertisers claim; it is to be found only in human hearts which have been cleansed of their sin in the Blood of the Lamb whose heart was broken that we might live the abundant life.1

And what about the fierce international scramble to find in helpless and backward nations a market on which to fob off all the superfluous rubbish which the inexorable machines of North America and Western Europe grind out hour by hour simply to create employment and make bigger profits? I have known black men in my birth place in Katanga, the Congo, who bought shining white electric stoves to put into their mud huts even though they had no electricity to make them work. Before the last war the Red Indians of my old mission station at Teslin in the Yukon Territory, Canada, were bamboozled into buying a Model T Ford even though no highway was available. In desperation the Indians drove it out onto the ice in wintertime just to see how far it would skid over the frozen Lake Teslin. Likewise poor Eskimos have been sold refrigerators in the Arctic Circle.

And what about the fierce international scramble to find in helpless and backward nations a market on which to fob off all the superfluous rubbish which the inexorable machines of North America and Western Europe grind out hour by hour simply to create employment and make bigger profits? I have known black men in my birth place in Katanga, the Congo, who bought shining white electric stoves to put into their mud huts even though they had no electricity to make them work. Before the last war the Red Indians of my old mission station at Teslin in the Yukon Territory, Canada, were bamboozled into buying a Model T Ford even though no highway was available. In desperation the Indians drove it out onto the ice in wintertime just to see how far it would skid over the frozen Lake Teslin. Likewise poor Eskimos have been sold refrigerators in the Arctic Circle.

We have been so corrupted by godless apostate standards and values that we now think of work as something one has to do to make money, rather than thinking of it in terms of the work done. Instead of asking of an industrial enterprise, "Will it pay?" we should be asking of it, "Is what you make really needed? Is it good?" Instead of asking a worker, "Does your work pay?" we should be asking him "What are the things you make worth?" And of the goods produced in our factories we should not be asking, "Can we induce people into buying them?" but "Are they useful things, well made?" Of employment we should be asking not "How much a week?" but "Will it exercise the worker's skills to the full?"

Imagine the consternation that would be caused at a meeting of the shareholders of Tetley's Brewery if one of the shareholders got up and demanded to know not where the profits went or what dividends were to be paid out, but in a loud and clear voice and with a proper sense of responsibility asked, "Mr. Chairman, just what does go into the beer our company makes?" Because our workers know only too well that such questions will never be asked by the shareholders of the companies for which the work, they could not care less what goes into the beer they produce.

Because their need for status and responsibility remains unsatisfied, our workers remain dissatisfied and discontented. According to Elton Mayo and his School for Human Relations in Industry, this lack of a sense of belonging and of being treated as a person is one of the commonest causes of neuroses in industry and is largely responsible for the social unrest of our times. As Canon V. A. Demant has pointed out in the symposium of lectures delivered during the last war at Dulwich College, published as Our Culture: Its Christian Roots and Present Crisis, all forms of 20th century collectivism, whether socialist, communist, or fascist, may be considered as reactions on the part of the Western world's workers to protect themselves against the gale set blowing by the attempts of economists and business men to reduce the workers to the demands of technical rationality, slaves of the machines and maximum profits regardless of the cost in human suffering.2

A brief examination of Anglo-Saxon economic and business history during the past three hundred years amply bears out the truth of Demant's statement. Unlike modern monopoly capitalism and international finance, early Anglo-American capitalism was not based upon the irresponsible exercise of economic power by a few over large masses of men. On the contrary, economic life was more or less controlled by a feeling of mutual responsibility between masters, journeymen, and apprentices. By and large, economic and labor relationships tended to be highly personal – between master and craftsman and journeyman and apprentice; laboring together in the same workshop; between buyer and seller living together in the same village or town. The very character of this relation produced some restraints upon the sinful human tendency of the master to exploit his workmen or the seller to cheat the buyer or the workman to produce sloppy goods or services.3 Following Lewis Mum-ford's account in Technics and Civilisation we may in fact distinguish three technological-industrial complexes – namely, that of the medieval "eotechnic" period, which lasted more or less in various Western nations until the middle of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; the "paleotechnic" phase of the Industrial Revolution, from which we have not yet altogether emerged; and the modern "neotechnic" phase of automation and mass production and consumption, still in process of development.4

a) Work in the Eotechnic Medieval Age⤒🔗

In the eotechnic period social organization was upon a feudal basis, the main material of industry was wood, and almost the sole sources of power were wind and water. The craftsman of the time, as opposed to the peasant, was normally a member of a craft guild, working at home for as many or as few hours as he pleased; he was a respected member of his local community, and he took great pride in his work.  It is true that his status was fixed from birth, but this was not felt to be a drawback, and it had the great advantage of providing security, freedom from anxiety, and above all a sense of belonging. Moreover, paradoxical as it may appear, social intercourse between classes of different levels was much freer than in the industrial society that later developed. Thus, for example, we read of many true romances where the apprentice boy grew up to marry the master's daughter, e.g., Dick Turpin. Membership in a guild, manorial estate, or village protected the individual throughout his life and gave to each person his own special role to play in society, and above all it gave him a sense of belonging to his community. Thus, while the Middle Ages suffered from plagues, appalling housing conditions, cruelty and superstition, lack of sanitation, in the sphere of human and labor relations conditions were often a great deal better and more satisfying than they have been since. Of the industrial psychology of this period J. A. C. Brown writes in his book, The Social Psychology of Industry:

It is true that his status was fixed from birth, but this was not felt to be a drawback, and it had the great advantage of providing security, freedom from anxiety, and above all a sense of belonging. Moreover, paradoxical as it may appear, social intercourse between classes of different levels was much freer than in the industrial society that later developed. Thus, for example, we read of many true romances where the apprentice boy grew up to marry the master's daughter, e.g., Dick Turpin. Membership in a guild, manorial estate, or village protected the individual throughout his life and gave to each person his own special role to play in society, and above all it gave him a sense of belonging to his community. Thus, while the Middle Ages suffered from plagues, appalling housing conditions, cruelty and superstition, lack of sanitation, in the sphere of human and labor relations conditions were often a great deal better and more satisfying than they have been since. Of the industrial psychology of this period J. A. C. Brown writes in his book, The Social Psychology of Industry:

Although a society in which status is fixed at birth may seem to have many drawbacks from the standpoint of the modern individual, it is likely to be forgotten that it also had many advantages. The anxiety and sense of insecurity which are inseparable from a competitive society with mobile status were avoided, everyone had a secure awareness of belonging ... At best, there was an affectionate and obedient attitude not only towards the real family, towards the father substitutes right up the hierarchy; the master of the guild, the lord of the manor, and finally the benevolent authority of the Church.5

No doubt it was for such reasons that England during the High Middle Ages was known as "Merrie England" as well as for the reason that the people enjoyed no less than one hundred and fifty "holydays" or public feast days during the year. Modern sources of power had not yet been tapped, and there were no machines and no labor-saving devices. Yet this was the period when the people of England enjoyed more leisure than they do today, and when real craftsmanship flourished in the land, as the visitor of our glorious cathedrals and beautiful old parish churches may still see for himself. Of the craft guilds of this former era Eric Lipson well wrote in his first volume of the Economic History of England:

The craft guilds had certain qualities which may still afford an inspiration to our own age ... The craft guild was admirably designed to achieve its object, the limited production of a well-wrought article. Apprenticeship afforded ample opportunities for a thorough system of technical training and the inspection of workshops stimulated and encouraged a high standard of craftsmanship. The regulation of prices and conditions of labour tended to protect the journeyman against arbitrary oppression ... The control of prices and the quality of wares was intended to protect both the seller and the buyer and to establish rates of remuneration for the craftsmen commensurate with the labour involved. Medieval authorities sought to fix prices according to the cost of production. Convinced that the labourer was worthy of his hire, their principle was to reward him with a recompense suitable to his station. They did not hold to the modern theory of minimum subsistence – the iron law, according to which earnings are forced down to the lowest level at which the artisan can subsist. Instead they seemed to have recognized that earnings should conform to a fit and proper standard of human life.6

b) Work in the Period of the Industrial Revolution←⤒🔗

The next stage was that of early mercantile capitalism, the domestic stage of industry, and the Industrial Revolution. Business and private affairs in this earlier stage of capitalism at their best tended to be governed by much the same moral and ethical code; a code which was based upon the Protestant emphasis upon the individual's personal accountability to God for both his business and his private conduct. The goal of Puritan Christianity in regard to social matters was the creation of a responsible self-disciplined body of free men and women, a citizenry of independent landholders, small businessmen, and self-respecting journeymen skilled in various trades and professions. R. C. K. Ensor's description of this evangelical motivation of an earlier generation of Anglo-Saxon businessmen deserves quoting:

The essentials of evangelicalism were three. First its literal stress on the Bible. It made the English the "people of a book" somewhat as devout Moslems are, but few other Europeans were. Secondly, its certainty about the existence of an after-life of rewards and punishments. If one asks how nineteenth century English merchants earned a reputation of being the most honest in the world (a very real factor in the nineteenth century primacy of English trade), the answer is: because hell and heaven seemed as certain to them as tomorrow's sunrise, and the Last Judgement as real as the week's balance sheet. This keen sense of moral accountancy had also much to do with the success of self-government in the political sphere. Thirdly its corollary that the presents life is only important as a preparation for eternity.7

The keystone of this mercantile capitalism was a sense of responsibility to the Lord for the conduct of one's business and personal life and a sense of self-reliance upon one's own efforts rather than upon the government. As Lord Lyndhurst once said in some famous words: "My lords, self-reliance is the best road to distinction in private life; it is equally essential to the character and grandeur of a nation." The classic expression of this doctrine of self-reliance was given by Samuel Smiles in his book, Self-Help, published in 1859.

Behind this evangelical morality there lay the great Reformation doctrine of the calling of the Christian man or woman to serve the Lord in everyday life as well as on the Lord's Day. From this doctrine of the calling has been derived the moral and spiritual dynamic which brought about the Industrial Revolution. By endowing common labor with Christian dignity and value Martin Luther and John Calvin gave the workers of the Reformed nations a new sense of their dignity and importance. As R. H. Tawney pointed out in Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, "Monasticism was, so to speak, secularized; all men stood henceforth on the same footing towards God."8

Had our Puritan forefathers not had a high sense of their calling to serve the Lord by a "godly self-discipline" at work, it is doubtful whether our modern industrial Atlantic society would ever have been built, depending as it does upon the need for men's courage, resource, endurance, persistence, precision, judgment, and reliability in dealing with machines.  It is thus no accident that the Industrial Revolution took place first in England, Holland, America, and the United States, the homelands of the Reformation, since the workers in these lands had, thanks to their evangelical and reformed upbringing, not only learned how to do an honest day's work but also to rediscover God's world. It is again no accident that the Industrial Revolution took place first in these homelands of Calvinism, for these had been the first to undergo the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, the prerequisite of any technical progress.

It is thus no accident that the Industrial Revolution took place first in England, Holland, America, and the United States, the homelands of the Reformation, since the workers in these lands had, thanks to their evangelical and reformed upbringing, not only learned how to do an honest day's work but also to rediscover God's world. It is again no accident that the Industrial Revolution took place first in these homelands of Calvinism, for these had been the first to undergo the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, the prerequisite of any technical progress.

The material potentialities of modern science might have waited in vain for their fulfilment, as had been the case with Greek mechanics in the ancient world, had it not been for the social and intellectual initiative and enterprise of Reformed Christians. This initiative received its moral dynamic from the Reformation. Historians such as Max Weber, M. J. Kitch, and Ernst Troeltsch have proved how much the Industrial Revolution owed to the moral and social ideas of Puritanism which inculcated the duty of unremitting industry and thrift while it discouraged rigorously every kind of self-indulgence.9

Other historians such as Stanford Reid of Guelph University and R. Hooykaas of the Free University, Amsterdam, have proved how much the Industrial Revolution in turn depended upon the work of such eminent Calvinistic scientists as Ambrose Pare, Bernard Palissy, Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and Peter Ramus. 10

All these men followed Calvin's method of arranging the facts of nature in categories so that they could see resemblances and relationships. Thus they began to develop a form of empiricism, whether in biblical studies, mathematics, the manufacture of pottery, the healing of wounds, or the development of a scientific method. Unlike the medieval schoolmen, these Reformed scientists believed that one must begin with the facts of God's creation if one would discover and understand the works of God's hands.

Such an empirical and experimental approach to God's world meant that these men exercised a considerable formative influence upon the development of physical science. Many have recognized the importance of Bacon in the rise of modern science, but have totally failed to link it to his Calvinistic presuppositions. Moreover, they have failed to see how his views derived from his forerunners such as Petrus Ramus, and were related to the scientific work of other Calvinists such as John Napier and the founding of the first center of British scientific studies by Sir Thomas Gresham in London.11 The fact is that to a considerable extent the Calvinistic thinkers of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries provided the only "scientific method" of the time which met the needs of the technical advances achieved by such men as Galileo, Stevin, and others. They laid down the principles of method later carried further by Huygens, Boyle, and, above all, Isaac Newton. In this way, their Reformed approach to the whole question of nature opened up new fields and directed men into areas of investigation leading to results of which we have not yet seen the conclusion. This Raymond Aron sums up in his Lectures on Industrial Society as the emergence of industrial society. "The major concept of our time is that of industrial society. Europe, as seen from Asia, does not consist of two fundamentally different worlds, the Soviet world and the Western world. It is one single reality: industrial civilization. Soviet and capitalist societies are only two species of the same genus."12

Following a suggestion of Max Weber's The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,13 the American sociologist, Robert K. Merton, shows in his essay, "Puritanism, Pietism and Science," available in his Social Theory and Social Structure,14 how the Puritans in England and the Pietists of Europe both greatly assisted the development of modern science, not only by their insistence upon a rational rather than a scholastic understanding of the "order of nature," but by encouraging men to master their material environment. He writes:

It is the thesis of this study that the Puritan ethic, as an ideal-typical expression of the value-attitudes basic to ascetic Protestantism generally, so canalized the interests of seventeenth century Englishmen as to constitute one important element in the enhanced cultivation of science. The deep-rooted religious interests of the day demanded in their forceful implications the systematic rational, and empirical study of Nature for the glorification of God in His works and for the control of the corrupt world.15

Merton backs up his thesis first by examining the attitudes of contemporary seventeenth century scientists such as the Puritan Robert Boyle as expressed in his book, Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy, and by the Puritan John Ray, founder of modern botany, in his work, The Wisdom of God. In the former Boyle maintained that the study of nature must always be to the greater glory of God and the good of man. In the latter book Ray constantly exalted the God who had created such an amazing and beautiful world. In a similar vein Merton shows that John Wilkins proclaimed in his Principles and Duties of Natural Religion that the experimental study of nature is the most effective means of begetting in men a veneration for God.

The Puritans also believed that the Christian is called upon to use his scientific discoveries for the improvement of man's fallen estate and for the comfort and welfare of mankind. By thus focusing attention upon the world in which men lived, Puritanism, Merton concludes, had brought about the fusion of rationalism and empiricism, the two values that together constitute the essence of the modern scientific spirit. He writes: "The combination of rationalism and empiricism which is so pronounced in the Puritan ethic forms the essence of the spirit of modern science ... Empiricism and rationalism were canonized, beatified, so to speak."

Merton in the second place supports his thesis by showing the great part played by both the Puritans in England and America and by the Pietists in Western Europe in establishing new educational institutions where the new empirical approach rather than the old scholastic one could be applied. In no institution did the Puritans in England play a greater role than in the Royal Society. He writes:

Among the original list of members of the Society of 1663, forty-two of the sixty-eight concerning whom information about their religious orientation is available were clearly Puritan. Considering that the Puritans constituted a relatively small minority in the English population, the fact that they constituted sixty-two per cent in the initial membership of the Society becomes even more striking.16

Both Puritans in England and the Thirteen Colonies of America and the Pietists in Europe broke with the prevailing methods of education and established their own "Dissenting Academies" as well as new universities.

Of this development Merton writes: "The emphasis of the Puritans upon utilitarianism and empiricism was likewise manifested in the type of education which they introduced and fostered." The "formal grammar grind" of the schools was criticized by them as much as the formalism of the Church.

Of this development Merton writes: "The emphasis of the Puritans upon utilitarianism and empiricism was likewise manifested in the type of education which they introduced and fostered." The "formal grammar grind" of the schools was criticized by them as much as the formalism of the Church.

Merton then refers to the great influence played by such Calvinist scholars as Samuel Hartlib, who sought to introduce the new realistic, utilitarian, and empirical education into England, forming the connecting link between the various Protestant educators in England and in Europe who were seeking to spread the academic study of science. Then there was the great Bohemian Reformed scholar, John Amos Comenius. Basic to the latter's educational philosophy were the norms of utilitarianism and empiricism, values which could only lead to an emphasis upon the study of science and technology, of Realia as opposed to Theoria. In his work Didactia Magna Comenius summarized his views:

The task of the pupil will be made easier, if the master, when he teaches him everything, shows him at the same time its practical application in everyday life. This rule must be carefully observed in teaching languages, dialectic, arithmetic, geometry, physics, etc.

The truth and certainty of science depend more on the witness of the senses than on anything else. For things impress themselves directly on the senses, but on the understanding only mediately and through the senses. Science, then, increases in certainty in proportion as it depends on sensuous perception.17

The Puritan determination to advance science not only bore fruit in the "Dissenting Academies" of England but also in the universities of Durham founded by Oliver Cromwell and of Harvard, where the new views of Comenius and Peter Ramus were taught instead of the classical science of Aristotle and of medieval scholasticism. Whereas in the older universities of Oxford, Paris, and Bologna the emphasis was still placed upon non-utilitarian classical studies, the Puritan and Pietist academies and universities held that a truly "liberal" education was one which was "in touch with life," and which should therefore include as many utilitarian subjects as possible. As Irene Parker points out in her Dissenting Academies in England: "The difference between the two educational systems is seen not so much in the introduction into the academies of "modern" subjects and methods as in the fact that among the Nonconformists there was a totally different system at work from that found in the universities. The spirit animating the Dissenters was that which had moved Ramus and Comenius in France and Germany and which in England had actuated Bacon and later Hartlib and his circle."18

Merton then refers to the work of F. Paulsen on German Education: Past and Present as well as of Alfred Heubaum, both of whom showed that the Pietists in Germany held similar educational views to the Puritans. Merton says: "The two movements had in common the realistic and practical point of view, combined with an intense aversion to the speculation of the Aristotelian philosophers. Fundamental to the educational views of the Pietists were the same deep-rooted utilitarian and empirical values which actuated the Puritans. It was on the basis of these values that the Pietist leaders, August Hermann Francke, Comenius, and their followers emphasized the new science."19

This preponderance of Protestants among scientists has been noted in other countries and has continued to the present.20 A study of American scientists completed after World War II concluded that the "statistics, taken together with other evidence, leave little doubt that scientists have been drawn disproportionately from American Protestant stock."21

Writing in his book, The Century of Revolution, the Master of Balliol College, Oxford and a former self-confessed Communist, Christopher Hill, had this comment to make regarding the connection between Calvinism and the rise of modern methods of production.

Calvinism liberated those who believed themselves to be the elect from a sense of sin, of helplessness; it encouraged effort, industry, study, a sense of purpose. It prepared the way for modern science ... The Puritan preachers insisted that the universe was law-abiding ... It was man's duty to study the universe and find out its laws ... Bacon called men to study the world about them ... The end of knowledge was "the relief of man's estate," "to subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity." Acceptance of this novel doctrine constituted the greatest intellectual revolution of the century.22

In his essay on "Protestantism and the Rise of Capitalism," contributed to Essays in the Economic and Social History of Tudor and Stuart England, Christopher Hill further elaborates upon the causal connection between Protestantism, economic growth, and capitalism. He does this by demonstrating the connection through the central issue of the Reformation, justification by faith:

The central target of the Reformers' attack was justification by works ... The Protestant objection was to mechanical actions in which the heart was not involved ... A Protestant thought he did it… For Christians no action can be casual or perfunctory, the most trivial detail of our daily life should be performed to the glory of God; should be irradiated with a conscious co-operation with God's purposes.23

From this central doctrine came two results. On the one hand, says Hill, "It was in fact the labour of generations of God-fearing Puritans that made England the leading industrial nation of the world."24 On the other hand, however, the individualism of the Protestants meant that while "the Roman Church was able slowly to adapt its standards to the modern world through a controlled casuistry, guiding a separate priestly cast ... Protestant ministers had to tag along behind what seemed right to the consciences of the leading laymen in their congregations."25 Hill concludes that:

There is nothing in Protestantism which leads automatically to Capitalism; its importance was rather that it undermined obstacles which the more rigid institutions and ceremonies of Catholicism imposed. But men did not become Protestants because they were Capitalists or Capitalists because they were Protestants."26

Protestant doctrine, however, Hill says, "gave a vital stimulus to productive effort in countries where Capitalism was developing at a time when industry was small scale, handicraft and unrationalized."27

Thanks to this Puritan stimulus, the standard of living of the English-speaking democracies was raised to a level never before reached in the history of mankind. A look at the economic position today of the leading nations of the world soon shows the decisive part played by Protestantism in raising men's physical standards of living consequent upon raising their spiritual standards of living. Taking the income per head of population as given in the British magazine, The Economist, 1962, as the best indication of national wealth, we find that the Protestant nations decisively head the list, followed by Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox lands.

NATIONAL INCOME PER HEAD AND PREDOMINANT RELIGION

(£ Sterling, 1961)

|

Reformed and Protestant |

Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox |

Non-Christian |

||||

|

1 |

United States |

824 |

||||

|

2 |

Sweden |

575 |

||||

|

3 |

Canada |

546 |

||||

|

4 |

Switzerland |

516 |

||||

|

5 |

New Zealand |

470 |

||||

|

6 |

Australia |

439 |

||||

|

7 |

Britain |

413 |

||||

|

8 |

Denmark |

411 |

||||

|

9 |

W. Germany |

383 |

||||

|

10 |

Israel |

373 |

||||

|

11 |

Norway |

370 |

||||

|

12 |

Belgium |

368 |

||||

|

13 |

France |

362 |

||||

|

14 |

Finland |

319 |

||||

|

15 |

Netherlands |

307 |

||||

|

16 |

Venezuela |

277 |

||||

|

17 |

Austria |

263 |

||||

|

18 |

Ireland |

203 |

||||

|

19 |

Italy |

199 |

||||

|

20 |

Chile |

179 |

||||

|

21 |

Japan |

144 |

||||

|

22 |

South Africa |

140 |

||||

|

23 |

Argentina |

135 |

||||

|

24 |

Jamaica |

133 |

||||

|

25 |

Greece |

130 |

||||

|

26 |

Mexico |

100 |

||||

|

27 |

Spain |

97 |

||||

|

28 |

Portugal |

90 |

||||

|

29 |

Yugoslavia |

80 |

||||

|

30 |

Ghana |

71 |

||||

|

31 |

Brazil |

48 |

||||

|

32 |

Ceylon |

44 |

||||

|

33 |

India |

25 |

||||

|

34 |

Burma |

18 |

The classification is governed by the religion predominating during the main period of economic growth of the country or what W. W. Rostow terms "the take-off" period. Rostow gives us the following table of some tentative, approximate take-off dates:28

|

Country |

Take-off |

Country |

Take-off |

|

Great Britain |

1783-1802 |

Russia |

1890-1914 |

|

France |

1830-1860 |

Canada |

1896-1914 |

|

Belgium |

1833-1860 |

Argentina |

1935- |

|

United States |

1843-1860 |

Turkey |

1937- |

|

Germany |

1850-1873 |

India |

1952- |

|

Sweden |

1868-1890 |

India |

1952- |

|

Japan |

1878-1900 |

In most cases the religion predominating during this period of industrial "take-off" does not differ very much from the religious affiliation given in the latest censuses. In some nations the Catholic population has grown substantially in the last two generations. Even so, in the United States there are still three Protestants to every two Roman Catholics, in Australia three to one, in Switzerland four to three. In the Netherlands, the Roman Catholics are now almost equal in numbers, and in Canada the Protestants are in a bare majority. (However, excluding Quebec, which has a lower per capita income, the Protestants are three to one.) In West Germany there are ten Protestants to nine Roman Catholics, but before the division of the country the ratio was nearer three to two. The distinction between Protestant and Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox is of course much finer than that which marks them off from non-Christian lands.

Is it purely a coincidence that the Western world and the Anglo-Saxon world, inspired by Christian ideals and morals, the inheritor of a thousand years of biblical preaching and teaching, is prosperous, whilst the two thirds which form the world's hungry billions are mostly found where the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Bread of Heaven, has not penetrated or taken strong root? Can we divorce Christianity in general and Calvinism in particular from the prosperity of the Western world, and especially of the English-speaking world? Do we not owe God something for our enormous agricultural surpluses? In starving India the land is overrun by millions of cattle and monkeys because they are considered to be sacred. No Hindu would dare to kill a cow for fear of offending his god, nor can the cattle and the monkeys be driven off the crops from which they consume the food so desperately needed for human beings, because the heathen gods would be upset. Here we have an obvious example of a false religion based upon superstition resulting in bad farming.

Thanks to the powerful influence of God's blessed Scriptures, the saving power of Christ, and the wisdom and science of God, European and North American farmers have stopped all sorts of superstitious farming practices and learned to farm their lands in accordance with God's great scientific laws for the "holy earth." If it had not been for the great Christian monastic orders of the Middle Ages, e.g., the Benedictines and the Cistercians, much of Europe's and Britain's land would have remained forest and bush-land. Thanks to the liberating power of God's Holy Word, Western men stopped living in fear and trembling of the evil spirits, sprites, and fairies whom as pagans they had previously supposed to inhabit every tree and bush. Thanks to the influence of the Bible upon their minds, Western men came to realize that the earth is the Lord's and that it operates according to laws which men are to unveil by means of their science.

Thanks to the powerful influence of God's blessed Scriptures, the saving power of Christ, and the wisdom and science of God, European and North American farmers have stopped all sorts of superstitious farming practices and learned to farm their lands in accordance with God's great scientific laws for the "holy earth." If it had not been for the great Christian monastic orders of the Middle Ages, e.g., the Benedictines and the Cistercians, much of Europe's and Britain's land would have remained forest and bush-land. Thanks to the liberating power of God's Holy Word, Western men stopped living in fear and trembling of the evil spirits, sprites, and fairies whom as pagans they had previously supposed to inhabit every tree and bush. Thanks to the influence of the Bible upon their minds, Western men came to realize that the earth is the Lord's and that it operates according to laws which men are to unveil by means of their science.

If India, Asia, and Africa are ever to raise their material standards of living, it is imperative that the peoples of these lands first raise up their spiritual, moral, and educational standards. What is the use of the Western world sending out modern farm machinery to the pagan peasants of Egypt and India and Africa gripped by the most heathen primitive superstitions, to whom the use of much modern farm equipment is contrary to the will of the false gods and idols they worship? Until such spiritual aid by way of Christian missionaries is first provided, all technical aid is simply a waste of time. Until the process of evangelization and Christian education is undertaken, we cannot expect the Afro-Asians to raise their material living standards. England and Europe had first to undergo the spiritual revolution of the Reformation before they underwent the scientific and then the industrial revolution. In Asian Drama, G. Myrdal claims that nothing less than a revolution, political, social, religious, philosophical, is the precondition of Western-style economic growth in the underdeveloped world of today.29

There is also evidence for the view that the strength or weakness of management would seem to be related to whether a country is Protestant. Studies published in America during 1959 by F. Harbison of Princeton and C. A. Myers of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, titled Management in the Industrial World,30 compared the quality of industrial management in the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Germany, France, Italy, Egypt, India, Chile, and Japan. The first four all appear to have achieved a high standard of industrial management on a fairly wide scale and have, of course, a high material standard of living. Standards of management among the other are reported to be much poorer, and, with the exception of France, they all have a very much lower standard of living. These weaknesses in management seem to run to a pattern in all non-Protestant countries, and they are traceable directly to ethical and religious causes. Managers in these non-Protestant lands are gravely concerned with their authority and the preservation of their prerogatives. They prefer docile employees "who will not talk back or raise questions," rather than employees who are ambitious or efficient.31 Typical organizational structure is highly centralized and personal. There is little delegation and consequently much frustration and bitterness on the part of subordinate managers. Key positions are occupied by family members on the basis of family ties and not on the basis of performance. The family is more important than the enterprise. Maximum production and performance have little place in the family plans. "The end supreme and all pervading, is the family – its economic security, its social prestige."32 The object of the business in these non-Reformed lands is to provide a reasonable degree of wealth for the family, and it is not felt that the productivity of the enterprise need be pushed beyond this point. All this contrasts sharply with the philosophy of management in the United States and Britain, where it is generally held to be intolerable that nepotism and personal interests should stand in the way of a major enterprise responsible for the employment and standard of living of thousands of workers.

Even non-Christian Japan, which has been most successful in catching up with advanced Western industrial countries, has an income per head only one half of that in Britain. The above authors comment, "Unless basic, rather than technical or trivial, changes are forthcoming, Japan is destined to fall behind in the ranks of modern industrial nations."33 Writing of France the authors comment:

Compared to other European countries, France, in the latter half of the Eighteenth Century was rich in the attributes required for an economy based on the exploitation of local resources. ... One would have had every reason to expect France, in the Twentieth Century, to be a leader in the world's industrial growth and progress ... By the end of the Nineteenth Century France was in the grip of a slow and continuous regression in its capacity to produce ... Other forces which would normally have exerted pressure for recrystallization of the economic institutions of France remained stubbornly inoperative in an economy of small holdings, an atmosphere of widespread absence of trust and an exalted idea of personal security.34

Is it without any significance that in the Roman Catholic Canadian Province, Quebec, as well as in other Roman Catholic lands, the leading executives of the bigger business organizations have tended to be Protestants rather than Roman Catholics? The usual reply made by French-speaking Canadians to this question, when it is raised in discussion, is that until recently the Protestants had the better system of education. But then one is forced to ask why do the Protestants have a better system of education by and large than the Roman Catholics, at least better in such districts as Quebec and southern Ireland? Again the answer goes back to the Reformation. As James Hastings Nichols points out in his classic work, Democracy and the Churches:

Roman Catholic and Anglican education was frankly aristocratic and designed to maintain social and political inequality. The notion of universal education and the common school has been inherited by modern democracy from the Reformation. The history of early public education knows no rival to the schools of Geneva, Scotland, and New England. The Reformed did not merely believe in the capacities of all men; they took pains to develop them.35

H. F. R. Catherwood warns us in his recent work, The Christian in Industrial Society, that the English-speaking Protestant nations cannot afford to boast of racial superiority. Whatever greatness they have achieved is due to Jehovah God and His Christ and not to any innate national characteristics or traits. He writes:

Humanism, the prevailing faith in many of the countries which are still nominally Protestant, may have taken over many of the ethical ideals of Christianity, but it remains to be seen whether, having taken away the theology, the "why" of religion, the ethic the "what" of religion will retain its grip. Only now are we encountering the third generation since the major decline of church-going. If the Christian faith ceased to have any influence in Northern Europe (or North America) but took a firm grip in, say Brazil, which has a growing Protestant minority, then the relative patterns of national prosperity and growth might change quite decisively over a relatively short period. It is, unfortunately, all too easy to imagine the deterioration which could set in here if management and labour increasingly took their tone from their worst elements.36

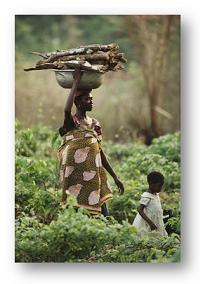

Whenever and wherever Reformed Protestant Christianity has decayed or failed to penetrate you will find ruthless greed, dishonesty, prejudice, passion, and slothfulness at work disrupting life. The writer will never forget seeing colored women in the former Belgian Congo and in the Yukon carrying home water and firewood while their menfolk sat watching them do all the work. Without Christ in control of men's consciences human society and industry falls apart into lawless violence, power with no trace of conscience, the jackboot of tyranny, injustice, and economic exploitation trampling down the weak, the poor, and the sick. When Christ is rejected by a majority of a nation, all defense against the exercise of arbitrary political and economic power vanishes too at the same time. It is the Lord Jesus Christ alone who can subject power to the control of conscience. Except the Lord build a nation's political and economic institutions they labor in vain who build.

Whenever and wherever Reformed Protestant Christianity has decayed or failed to penetrate you will find ruthless greed, dishonesty, prejudice, passion, and slothfulness at work disrupting life. The writer will never forget seeing colored women in the former Belgian Congo and in the Yukon carrying home water and firewood while their menfolk sat watching them do all the work. Without Christ in control of men's consciences human society and industry falls apart into lawless violence, power with no trace of conscience, the jackboot of tyranny, injustice, and economic exploitation trampling down the weak, the poor, and the sick. When Christ is rejected by a majority of a nation, all defense against the exercise of arbitrary political and economic power vanishes too at the same time. It is the Lord Jesus Christ alone who can subject power to the control of conscience. Except the Lord build a nation's political and economic institutions they labor in vain who build.

Upon being appointed American ambassador to Brazil, Mr. Babson went to say goodbye to the President of the Argentine Republic. After luncheon the two men sat in the sun parlor of the presidential palace overlooking the river. The President was very thoughtful. "Mr. Babson, I have been wondering why it is that South America with all its great natural resources and advantages is so far behind North America." As a guest, Mr. Babson relates in his book, Fundamentals of Prosperity, he did not like to suggest any reason, so he replied, "Mr. President, what do you think is the reason?" The President replied, "I have come to this conclusion. South America was settled by the Spaniards who came to South America in search of gold, but North America was originally settled by the Pilgrim Fathers who went there in search of God."37

The point of view of the Reformation of seeing all things "sub specie aeternitas" not only helped greatly in the development of an inductive method in natural science; it also provided a new moral approach to the use of the things of this world. Calvin and his followers did not see the world as something evil from which man should fly, but rather holding to their doctrine of the sovereignty of God, they believed that God had placed man in this world to exploit its potentialities to the best of his ability that he might glorify God. Under the orders of God, man has the responsibility of developing a material and social culture which would manifest the goodness and the power of God, thus providing man with "the good life." And even though man has sinned in his attempt to claim this world for himself as its true lord, he still has this responsibility and the ability, albeit corrupted, to do so. By virtue of this new moral dynamic, the Calvinists, instead of running away from human culture like so many later pietists, sought to conquer the world for Christ's sake. They sought to glorify God in His Church and to serve Him in His world.38

Thus there developed in the lands of the Reformation a new perspective on the world. The old medieval Catholic ideal of ascetism and withdrawal was rejected by Protestant Christians in favor of a new ideal of using and enjoying the creation to the glory of God. This meant use in moderation and in accordance with the righteousness which God demands of His people. It was men endued with this new ideal who provided the driving power of Anglo-American and Dutch capitalism and who were the founders of the economic power of Great Britain, Holland, and America. Thanks to these Puritan merchant adventurers, business men, and entrepreneurs, the standard of living of Britain, Holland, and America was raised to a level never before reached in the history of mankind.

Owing to the propaganda of such socialist historians as the Webbs, the Hammonds, and R. H. Tawney, it has become fashionable to decry these Puritan capitalists and to look upon the Industrial Revolution as an unmitigated disaster. Replying to this caricature of economic history, T. S. Ashton, Professor of Economic History in the University of London, points out that it is perverse to maintain the view that technical and economic changes were themselves the source of the calamity. In his classic little book on The Industrial Revolution he writes:

The central problem of the age was how to feed and clothe and employ generations of children outnumbering by far those of any earlier time. Ireland was faced by the same problem. Failing to solve it, she lost in the "forties" about a fifth of her people by emigration or starvation or disease. If England had remained a nation of cultivators and craftsmen, she could hardly have escaped the same fate, and, at best, the weight of growing population must have pressed down the spring of her spirit. She was delivered, not by her rulers, but by those who, seeking no doubt their own narrow ends, had the wit and resource to devise new instruments of production and new methods of administering industry. There are today on the plains of India and China men and women, plague-ridden and hungry, living lives little better to outward appearance, than those of the cattle that toil with them by day and share their places of sleep by night. Such Asiatic standards, and such unmechanized horrors, are the lot of those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution.39

And we might add without passing through a spiritual revolution such as the people of the Reformation lands passed through during the sixteenth century. When Macaulay compared his own day with the past, it was inevitably to rejoice in the change. Since popular economic history was taken over by the Fabians and socialists, any similar contemporary comparison would equally inevitably be a cause for lamentation. In a very important recent work on Capitalism and the Historians it has been proved how the structure of left-wing historiography (the political purpose of which was largely hidden from subsequent generations of school children in English and American schools) depended for its emotional appeal on forgetting Thomas Malthus and his discoveries about population increases in relation to diminishing physical resources as quickly as possible. Actual case studies of the English factory system and the conditions of life of the English workers buttress the conclusions of the authors. Messrs. T. S. Ashton, L. M. Hacker, Bertrand D. Juvenel, and W. H. Hutt have proved that under capitalism the workers, despite long hours and other hardships of factory life, were better off financially, had more opportunities, and led a better life than had been the case before the Industrial Revolution.40

It is into this heresy of regarding the operations of "capitalism" as a voluntary process which most socialist historians seem to have fallen. To these writers the growth of population was merely a consequence of industrialism. But this is to neglect the research of the past thirty years which has upset the thesis that industrialism "created" the economic problem.

Economic change means a change of institutions, habits, ideas, and attitudes; it takes place, partially at any rate, because the old institutions, habits, ideas, and attitudes have become ossified or purposeless and obstructive. Behind the change from the defensive social and economic policies of the Middle Ages to the offensive, "individualistic" economic policies of the nineteenth century is one major factor: the consciousness of man's increased power over nature. The age of Malthus was in some respects as short of the indispensable necessities as the age of Aquinas, but it was equipped with better tools and blessed with business entrepreneurs whose vision pierced beyond the contemporary gloom to glimpse the age of plenty beyond. Answering the question, "Why did the first industrial 'take-off' happen in Britain and not in France or elsewhere?" W. W. Rostow writes in his fundamental work, The Stages of Economic Growth:

And so Britain, with more basic industrial resources than the Netherlands; more nonconformists, and more ships than France; with its political, social and religious revolution fought out by 1688 – Britain alone was in a position to weave together cotton manufacturing, coal and iron technology, the steam engine, and ample foreign trade to pull it off.41

Thus the economic primacy of Victorian England cannot be explained entirely in terms of natural resources, James Watt, and a fortunate absence of foreign competition. In the final analysis it was due to the men of wit and infinite resource and courage who felt called by their Reformed faith in the living God to carry out the Creator's cultural mandate "to have dominion over the earth and to subdue it."

c) Work in the Age of Automation and Mass Production←⤒🔗

By the eighteen eighties of the last century the spirit and structure of this early Anglo-American capitalism underwent a profound and revolutionary change as new methods of the organization of capital, new methods of production and distribution were devised and as apostasy triumphed over Christian faith. A whole new collection of business devices and ceremonials were developed in the industrial and commercial world which enabled apostate business men to set aside the moral scruples and Puritan ethic which had formerly governed the lives of their grandfathers and fathers.

Of these legal devices none has been more insidious than the invention of the limited liability company and the modern business corporation. Such business corporations have one outstanding feature; viz., they are completely irresponsible, having neither bodies to be kicked nor souls to be damned. Beyond good and evil, insensible to argument or moral appeal, they symbolized the mounting independence of modern monopoly capitalism and international finance from the old restraints and scruples of Christianity both Roman Catholic and Reformed.

"As directors of a company," wrote William M. Gouge, "men will sanction actions of which they would scorn to be guilty in their private capacity." A crime which would press heavily on the conscience of one man becomes quite endurable when divided among many. "Where the dishonesty or fraud or exploitation has become the work of all members of a business every such business man can now say with Macbeth in the murder of Banquo, 'Thou canst not say I did it.'"42

As industry became more mechanized and passed out of the hands of owners of capital into that of the managers of capital, economic life became depersonalized and industry became more autocratic and oligarchic in its structure. In their classic work, The Modern Corporation and Private Property,43 Adolf Berle, Jr., and Gardiner C. Means showed what had taken place by 1925. Nominal powers of decision over the use of capital had become whittled down to pro forma annual meetings of shareholders attended by perfunctory, negligible, or cranky minorities. As Burnham so well explained in his book The Managerial Revolution,44 the executive and managerial classes had in effect taken over the de facto control of Anglo-American productive processes. As Burnham sees it the technical and industrial society in which we now live is developing into something that may best be described as an administrative or managerial society. He says:

We are now in a period of social transition ... from the type of society we have called capitalist or bourgeois to a type of society which we have called managerial ... What is occurring today is a drive for social dominance, for power and privilege, for the position of ruling class, by the social group or class of managers ... The economic framework in which this social dominance of the managers will be assured is based upon the state ownership of the major instruments of production.45

In support of this thesis Burnham points out that a new class in managerial and administrative positions is multiplying in numbers and increasing in power throughout the world. With increasing mechanization in industry and the increasing bureaucratization of society we can therefore envisage a state of things when this new administrative class will outnumber the industrial wage earners. Moreover, while the initial impulse towards the growth of administration comes from the necessity of controlling a force so powerful as mass production, the tendency of administration in accordance with Parkinson's Law is to extend its numbers and its control over the whole of the life of modern industrial society. Even the professions, such as scientific research, medicine, and teaching, are in danger of becoming subject to "technique" and to the central bureaucratic direction and regulation, which such "technique" makes necessary.

By such "technique," Jacques Ellul points out in The Technological Society,46 we should understand not mere machine technology. Technique refers to any complex of standardized means for attaining a predetermined result. Thus, it converts spontaneous and unreflective behavior into behavior that is deliberate and rationalized Technique as Ellul would have us understand it means nothing less than the organized ensemble of all individual techniques which have been used to secure any end whatsoever. He writes: "Technique is nothing more than means and the ensemble of means."47 As such, technique has become indifferent to all traditional human ends and values by becoming an end-in-itself. The Technical Man is fascinated by results, by the immediate consequences of setting standardized devices into motion. He is committed to the never-ending search for "the one best way" to achieve any designated objective. Our erstwhile means have in fact all become an end, an end, moreover, which has nothing human in it and to which we must accommodate ourselves as best we may. We cannot even any longer pretend to act as though the ends justified the means. According to Ellul, technique, as the universal and autonomous technical fact of our age, is revealed as the technological society itself in which man is but a single tightly integrated and articulated component. The Western world is becoming a progressively technical civilization; by this Ellul means that the ever-expanding and irreversible rule of technique is extended to all areas of modern life: the economic, political, medical, administrative and police powers of the modern state, propaganda, and, above all, warfare. It is a civilization committed to the quest for continually improved means to carelessly examined ends.  Indeed, technique transforms ends into means. What was once prized in its own right now becomes worthwhile only if it helps to achieve something else. And, conversely, technique turns means into ends. "Know-how" takes on an ultimate value. Today men look to technique to save them from disaster as once men used to look to God. As Ellul well puts it: "Even people put out of work or ruined by technique, even those who criticize or attack it have the bad conscience of all iconoclasts. They find neither within nor without themselves a compensating force for the one they call in question. They do not even live in despair, which would be a sign of their freedom. This bad conscience appears to me to be perhaps the most revealing fact about the new sacralization of modern technique." He then points out that the characteristics of modern technique, namely, its rationality, artificiality, automatism, self-augmentation, monism, universalism, and autonomy, make it utterly different from the techniques of the past. "Today we are dealing with an utterly different phenomenon." The Technical Society is a description of the way in which this new technique is in process of taking over the traditional values of every society throughout the world, subverting and suppressing these values to produce eventually a monolithic world culture in which all nontechnological difference and variety is mere appearance.

Indeed, technique transforms ends into means. What was once prized in its own right now becomes worthwhile only if it helps to achieve something else. And, conversely, technique turns means into ends. "Know-how" takes on an ultimate value. Today men look to technique to save them from disaster as once men used to look to God. As Ellul well puts it: "Even people put out of work or ruined by technique, even those who criticize or attack it have the bad conscience of all iconoclasts. They find neither within nor without themselves a compensating force for the one they call in question. They do not even live in despair, which would be a sign of their freedom. This bad conscience appears to me to be perhaps the most revealing fact about the new sacralization of modern technique." He then points out that the characteristics of modern technique, namely, its rationality, artificiality, automatism, self-augmentation, monism, universalism, and autonomy, make it utterly different from the techniques of the past. "Today we are dealing with an utterly different phenomenon." The Technical Society is a description of the way in which this new technique is in process of taking over the traditional values of every society throughout the world, subverting and suppressing these values to produce eventually a monolithic world culture in which all nontechnological difference and variety is mere appearance.

The vital influence of technique is, of course, most evident in the economy. Ellul here first points out that technique not only plays a dominant role in production, as Karl Marx recognized, but also in distribution. Ellul remarks:

No area of economic life is today independent of technical development. It is to Fourastie's credit that he pointed out that technical development controls all contemporary economic evolution from production operations to demography ... Even more abstract spheres are shown by Fourastie to be dominated by technical progress; for example, the price mechanism, capital evolution, foreign trade, population displacement, unemployment, and so on ... As a result of the influence of techniques, the modern world is faced with a kind of "unblocking of peasant life and mentality." For a long time peasant tradition resisted innovation, and the old agricultural systems preserved their stability. Today technical transformation is an established fact; the peasant revolution is in process or already completed, and everywhere in the same direction.48

According to Ellul, technique is producing a growing concentration of capital as Marx foresaw it would. He writes, "Technical progress cannot do without the concentration of capital. An economy based on individual enterprise is not conceivable, barring an extraordinary technical regression. The necessary concentration of capital thus gives rise either to an economy of corporations or to a state economy ... This tendency toward concentration is confirmed daily. The important thing is to recognize the real motive force behind it."49 Ellul claims that the motive force behind this concentration of capital in giant corporations is not to be found in any human, social nor even economic benefits. "What, then, is the motive force behind this concentration?" he asks. The answer he gives is that it is technique alone. Ellul explains the reason:

A number of elements in technique demand concentration. Mechanical technique requires it because only a very large corporation is in a position at the present to take advantage of the most recent inventions. Only the large corporation is able to apply normalization, to recover waste products profitably, and to manufacture byproducts. Technique applied to problems of labor efficiency requires concentration because only through concentration is it possible to apply up-to-date methods which have gone far beyond the techniques of the former efficiency and time-study experts (for instance, the application of techniques of industrial relations). Finally, economic technique demands both vertical and horizontal concentration, which permits stockpiling at more favorable prices, accelerated capital turnover, reduction of fixed charges, assurance of markets, and so on ... The impulse to concentrate is so strong that it takes place even contrary to the decisions of the State. In the United States and in France, the State has often opposed concentration, but ultimately it has always been forced to capitulate and to stand by impotently while the undesired development occurs. This confirms my judgement concerning the decisive action of technique on the modern economy.50

The combined effect of all these changes and tendencies then has been to produce an industrial society dominated by "functional or technical rationality." The adjective is necessary to distinguish this meaning of rationality from the belief in the "understanding" as a quality in men which impels them to seek and enables them to apprehend truth and justice. Technical rationality is the capacity of applying means to ends or of organizing actions in order to reach a previously defined goal. It is in the production and distribution of goods and services that technical rationality has today come to exercise undisputed sway, and because of the dominant position of industry in modern society the habit of thinking in terms of technical rationality has spread imperceptibly into other areas of modern life.

In the drive for lower costs and greater output per man hour all the technical skills of industrial engineering and production planning are enlisted. The effort to break down work into simpler operations never ceases. The demands of the competitive market compel management to make new experiments and to employ new methods in the most economical use of capital and labor.

In such an increasingly urbanized, rationalized, and technicized society, controlled largely by impersonal money trusts, the majority of Western workers today spend most of their working hours under the direction of an authoritarian and disciplined business organization. The individual worker in our new age of mass production and of automation tends to become an anonymous, interchangeable unit. Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Jacques Ellul, H. Van Riessen, and Friedrich Georg Juenger, in their brilliant expositions of the effects of rationalized production on human beings, have shown how in some particular features the inner essence of this process has been startlingly revealed. It is characteristic of an age of machine production that in some industries it is necessary for some men to work in shifts. Machines tire less quickly than men; they need less prolonged periods of rest. It is they that set the pace, and when they are working at its full stretch it takes three men to keep up with them. The unit of production is no longer one man, but three "shifts." The person has become an anomymous, interchangeable unit. He can be represented by a number. In discussing the functional implications of this assembly line method of production Juenger writes in his book, The Failure of Technology:

An invention like the assembly line shows functional thinking to a high degree, for here all the functions of work are lined up within the sequence of lifeless time, and the workmen stationed along the line as functionaries of a work process that has been cut into pieces. What is the consequence? The worker loses his identity; as a person he loses his individuality; he is only noticeable as the performer of a function. As a human figure he fades out; and from the point of view of technical progress it would be desirable if he faded out altogether.51

Again, in modern industry payment is usually by the hour. It does not alter the significance of this fact that in earlier periods payment was also sometimes by the hour. The point is that it belongs to the essential nature of modern industry that time is no longer calculated in terms of the services of known persons, but by the hours of labor of anonymous interchangeable labor forces. The hour for which a man engaged in building a bridge is paid is not part of his life; it is part of the several hundred thousand hours required for the building of the bridge. Working time, that is to say, is disconnected from the man who does the job and related exclusively to the piece of work. In other words, a man's work is divorced from his personal life. The breaking up of the worker's life into a succession of identical units which he cannot combine into any meaningful scheme takes from him the power to order his life as a whole. The worker in the large factory has the feeling of being nothing more than a number. The growing size of industry is mainly responsible for this situation. It has resulted in the loss of personal contact with the company and of any awareness of working together in a common undertaking.52

Again, in modern industry payment is usually by the hour. It does not alter the significance of this fact that in earlier periods payment was also sometimes by the hour. The point is that it belongs to the essential nature of modern industry that time is no longer calculated in terms of the services of known persons, but by the hours of labor of anonymous interchangeable labor forces. The hour for which a man engaged in building a bridge is paid is not part of his life; it is part of the several hundred thousand hours required for the building of the bridge. Working time, that is to say, is disconnected from the man who does the job and related exclusively to the piece of work. In other words, a man's work is divorced from his personal life. The breaking up of the worker's life into a succession of identical units which he cannot combine into any meaningful scheme takes from him the power to order his life as a whole. The worker in the large factory has the feeling of being nothing more than a number. The growing size of industry is mainly responsible for this situation. It has resulted in the loss of personal contact with the company and of any awareness of working together in a common undertaking.52

Economists of the "classical" and even some modern schools of economic thought have furthered this process of the devaluation of labor by their definition of labor as a "commodity" along with other commodities in the general system of production and exchange. As the opening to his chapter "On Wages" Ricardo states that "Labor, like all things bought and sold and which may increase or decrease in quantity has its natural and market value. The natural price is that price which is necessary to enable labourers, one with another to subsist and to perpetuate their race without either increase or diminution." 53

In his recent work, Man, Industry and Society, Rodger Charles argues with a great deal of justification that it is just this theorem, that labor is a commodity, which is at the root of so much present-day labor-management conflict. Unfortunately, he points out, not only is it accepted as axiomatic by an old fashioned type of management but also by an equally old fashioned type of trade union leader.54

In so far as man in his work is reduced to the position of a mere functionary, who carries out a mechanical task in which he is replaceable by others, and in so far as he is treated as just another "commodity," work loses its personal quality. It ceases to be a sphere of personal and moral activity. It no longer fosters, as God means it to foster, the growth of personal character, by affording opportunities for personal decision, exercise of judgment, mastery of intractable material, and growth in understanding and skill.

Given such developments it is not surprising that so many industrial workers today are unable to find any meaning in their work and that they have been reduced to the level of "mass men."

The research work of the Elton Mayo School of Human Relations in Industry has provided us with first hand evidence of this depersonalization of men's labor in modern society. Mayo based his whole analysis of industrial society upon the concept of "anomie," i.e., the lost, forlorn condition of the little man in the vast industrial machine. Mayo found that this feeling of "anomie" acquired its typical character from the new, impersonal method of modern business organization and the so-called "scientific management" of workers introduced by Frederick Winslow Taylor, first at Midvale Iron Works, then at the Bethlehem Steel Company, and the resulting specialization of functions. The atomization of labor, and especially the isolation of a partial function and its resulting fixation, had given the workers at the Hawthorne Works of the Western Electric Company a feeling of being alone in their work, of not really belonging. Mayo discovered something drastically wrong with the social structure of the factory. The workers no longer counted in the formal organization of the plant or within the informal organization; i.e., in their personal relations with the foremen. As a result there had arisen all sorts of social tensions for which Mayo proposed radical new solutions based upon the following discoveries: (1) Work is a group activity; ( 2 ) the social world of the adult is primarily patterned about work activity; ( 3 ) the need for recognition, security, and a sense of belonging is more important in determining the worker's morale and productivity than the physical conditions under which he works; (4) a complaint is not necessarily an objective recital of facts; it is commonly a symptom manifesting disturbance of an individual's status position; (5) the worker is a person, whose attitudes and effectiveness are conditioned by social demands from both inside and outside the work plant; (6) informal groups within the work plant exercise strong social controls over the work habits and attitudes of the individual worker; (7) the change from the older type of community life to the atomistic society of isolated individuals, i.e., from eotechnic to neotechnic society, tends continually to disrupt the social organization of a work plant and industry generally; (8) group collaboration must be planned for and developed. If group collaboration is achieved, the work relations within a work plant may reach a cohesion which resists the pull towards stasis and atomization.55