The Communist Theory of Labor, Industry and Society

The Communist Theory of Labor, Industry and Society

a) The Marxist Analysis of Industrial Society⤒🔗

Marxism developed during the nineteenth century in reaction to the laissez faire theories of the classical economist who taught that the true welfare of society would prevail only when individuals could pursue their own private interests without any economic control by the state. As long as the state does not interfere in the free play of economic forces, then it was believed a "natural harmony" or identity of interests would work to bring about the prosperity of all. In this way, civil society had come to be regarded as the free play of economic interests within the juridical frame of the unassailable natural rights of the individual. As Adam Smith had said in The Wealth of Nations:

By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, the individual intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was not part of his intention … By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

The natural effort of every individual to better his own conditions when suffered to exert itself with freedom and security, is so powerful a principle, that it is alone without any assistance, not only capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity, but of surmounting a hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often encumbers its operations.1

In these famous passages Adam Smith had enunciated the basic principle of modern capitalism – the automatic regulation of industry by reference to market price alone. Smith believed that the fiscal policies of mercantilism had cramped individual enterprise and were holding back the economic growth of Britain. In the first passage we have quoted, Smith was exposing the ineptitudes of the corn bounty; in the other he was exalting private enterprise above paternalism, which allowed monopoly privileges to such trading companies as the East India Company and the Hudson Bay Company. In a famous essay titled The End of Laissez-Faire, John Maynard Keynes writes:

In these famous passages Adam Smith had enunciated the basic principle of modern capitalism – the automatic regulation of industry by reference to market price alone. Smith believed that the fiscal policies of mercantilism had cramped individual enterprise and were holding back the economic growth of Britain. In the first passage we have quoted, Smith was exposing the ineptitudes of the corn bounty; in the other he was exalting private enterprise above paternalism, which allowed monopoly privileges to such trading companies as the East India Company and the Hudson Bay Company. In a famous essay titled The End of Laissez-Faire, John Maynard Keynes writes:

The early nineteenth century performed a miraculous union. It harmonized the conservative individualism of Locke, Hume, Johnson and Burke with the Socialism and democratic egalitarianism of Rousseau, Paley, Bentham and Godwin … The age would have been hard put to it to achieve this harmony of opposites if it had not been for the Economists, who sprang into prominence just at the right moment. The idea of a divine harmony between private advantage and the public good is already apparent in Paley. But it was the Economists who gave the notion a good scientific basis … To the philosophical doctrine that Government has no right to interfere, and the divine miracle that it has no need to interfere, there is added a scientific proof that its interference is inexpedient. This is the third current of thought, just discoverable in Adam Smith, who was ready in the main to allow the public good to rest on "the natural effort of every individual to better his own condition," but not fully and self-consciously developed until the nineteenth century begins. The principle of laissez faire had arrived to harmonise Individualism and Socialism, and to make at one Hume's Egoism with (Bentham's) Greatest Good of the Greatest Number.2

Smith's conception of man is a typically apostate humanist one. Man is a reasonable and reason-determined being who lives out of his freedom and independence in seeking his own selfish interests to the fullest possible degree. He believed that such enlightened selfishness is the basic motivating force of every human being. It is not without significance that Smith wrote a treatise on The Theory of the Moral Sentiments before he turned his attention to the study of economics. In his ethical work he laid the philosophical foundations for the Wealth of Nations. Although influenced by Hutcheson's principle of benevolence, Smith was too skeptical a man to rest his ethical views upon unalloyed human kindness. Instead, he argued that we acted as we did out of a regard for the opinion of others. We shape our actions to please an impartial observer, the possessor of an enlightened reason. What we call conscience is the representative within our own breast of the enlightened observer. When we sympathize with a friend in trouble, our criteria are those we conceive will win the approval of this judicious soul. Such an observer of all our actions does not teach universal benevolence. Though he feels the softer human emotions, he expects human beings to pursue their own interest, in ways which violate no ethical canons. It is sympathy which serves as a brake upon a man's egoism. As a rational being man judges his own conduct by what others say and think of it and this keeps his selfishness within bounds.

Applying this faith in human reasonableness to economic conduct, Smith argued that competition in business life has the same mitigating effects on human cupidity as sympathy in one's own private life. The outcome of man's natural sympathy towards others, if allowed to run its course, would be a harmonious and natural order in economic life. The interest of one business man would always be in harmony with the interest of the next one. Smith was convinced that such competition would ensure that in the long run the price of goods would come to rest at the level of their labor value.

Smith believed that in primitive society "the whole produce of labour belongs to the labourer; and the quantity of labour commodity employed in acquiring or producing any commodity, is the only circumstance which can regulate the quantity of labour which it ought commonly to purchase, command, or exchange for."3 Smith recognized that property and profits are an imposition upon the workers. There is a note of nostalgia for "that original state of affairs" when the worker had "neither landlord nor master to share with him."4

But Adam Smith is hard-headed. His book is devoted not to moral sentiments but to expediency. The way lies ahead, through the increasing productivity that follows the division of labor.

For Smith the state should not intervene in economic life, since everyone bound to the "market" with its healthy competition, would find that his own individual freedom was in harmony with the economic interests of his fellow-men. The market itself would function as the natural force which would, sooner or later, make for equilibrium, since in Smith's system market and competition are equivalent. Competition presuppose factors that are mutually about equal. The functioning of competition in the market place thus presupposes the equality of those engaged in it. Economically engaged people, Smith believed, are equal people.

Smith's ethical and economic teaching is purely immanentistic, since he reduces man to homo oeconomicus in order that he could proclaim universally valid "laws" of human behavior in the economic sphere. As such, the father of modern humanistic economics is revealed as being in the grip of the apostate "nature-freedom" ground-motive. In future economic thought homo oeconomicus came to replace real flesh and blood men and was used to justify the exploitation of the workers in the new factories rising up all over Western Europe in the nineteenth century. Without this monstrous economic abstraction, the classical economists believed that economic theory could not develop and discover the laws which operate in economic life. Acceptance of this hypothesis enabled economists, however, to find such laws which could then be used against the workers. Marcet's Conversations in Political Economy is quoted by M. Dobb in his Wages to illustrate this. Her instruction of the unfortunate Caroline brings out very clearly how these new economic laws always worked in favor of the propertied and powerful. Since wages depend on the proportion of capital to workers, nothing must be done to decrease the riches of the rich; no poor-rate which leaves less money available for capital investment, no taxes which diminish the sum from which the wages will be paid. In fact, any effort at taking money from the rich will make the poor poorer; a strange but comforting teaching for the rich. One immediate practical conclusion was that the unions could not raise wages; only an increase in the wages fund could do that.5 Of this appeal to so-called "laws of nature" J. C. Gill writes in The Mastery of Money:

Smith's ethical and economic teaching is purely immanentistic, since he reduces man to homo oeconomicus in order that he could proclaim universally valid "laws" of human behavior in the economic sphere. As such, the father of modern humanistic economics is revealed as being in the grip of the apostate "nature-freedom" ground-motive. In future economic thought homo oeconomicus came to replace real flesh and blood men and was used to justify the exploitation of the workers in the new factories rising up all over Western Europe in the nineteenth century. Without this monstrous economic abstraction, the classical economists believed that economic theory could not develop and discover the laws which operate in economic life. Acceptance of this hypothesis enabled economists, however, to find such laws which could then be used against the workers. Marcet's Conversations in Political Economy is quoted by M. Dobb in his Wages to illustrate this. Her instruction of the unfortunate Caroline brings out very clearly how these new economic laws always worked in favor of the propertied and powerful. Since wages depend on the proportion of capital to workers, nothing must be done to decrease the riches of the rich; no poor-rate which leaves less money available for capital investment, no taxes which diminish the sum from which the wages will be paid. In fact, any effort at taking money from the rich will make the poor poorer; a strange but comforting teaching for the rich. One immediate practical conclusion was that the unions could not raise wages; only an increase in the wages fund could do that.5 Of this appeal to so-called "laws of nature" J. C. Gill writes in The Mastery of Money:

Too often in the past, men's theories have been represented to be "laws of nature," hindering the proper ordering of society. The factory laws and the humanizing of the scandalous Poor Law of 1834 came about because there were people who valued human life and believed in God, and refused to accept the expert opinions of the political economists of their day. They would not be silenced by them. From then to now, laws and customs have developed which it was forecast, would accomplish the nation's ruin.6

In the abstraction of homo oeconomicus we find, therefore, more than a fiction; it shows us the power of apostate humanist ground-motives in determining what godless men will "see" around them. In classical economics there is reflected a view of man as the sovereign ruler of his own destiny. Unfortunately the idea of homo oeconomicus still rears his ugly head in most modern economic textbooks. In his fascinating dissertation Vrijheid en Gelijkheid (Liberty and Equality) A. Kouwenhoven has clearly demonstrated that in contemporary economic literature the same apostate humanist view of man as the master of his own destiny still dominates Western economists as it did the classical economists.7 They refuse to admit that people today are not really free or equal and that the people are slowly being reduced to slaves of either big business or big government. Such economists can blithely discuss such subjects as poverty, monopolies, labor-management conflicts and yet still talk about the individual's freedom of choice. They must surely know full well that people today are not free in all respects nor that they are equal in various ways. Maarten Vrieze rightly points out:

This humanist idea of the essential equality of all men as reasonable individuals or units, existing as sub-stances in and by themselves free from any law order which is not fully derived from man himself (either as absolutized "reason" or as a more "positive" law of some kind), continues its existence even when people take notice of factual situations of inequality; the idea then functions as the "ideal" or "norm" according to which the situation must be rectified. And even there where such a conclusion is not explicitly drawn, the concept shows up suddenly in theoretical reflections … The economist, for example, will make very clear that he is aware of the concrete differences which exist in society … but at the same time he will introduce standards and yardsticks with which he begins to measure the economic activities of large numbers of people; he can only do so upon the presupposition that there is an underlying equality … The humanist has no other means of seeing any order in the economic phenomena; it escapes his attention – because his heart is closed for Him who sets them – that there are economic norms in which man functions whatever he does … It also escapes his attention that there are specific social structures which qualify the activities of man. It was necessary for humanism, again and again, to pose the premise of the uniformity of economic life: theory building would otherwise have been impossible. But every time it began to emphasize this uniformity, this visualizing of man as a unit which one can manipulate to construct universally determining laws, resistance came up. The science ideal kept coming into conflict with the personality ideal, and this picture has not yet changed in the 20th century.8

The powerful principle of self-love and of the identity of interests when used to define social responsibilities, had results which were wholly evil. In the name of laissez faire economic individualism, employers during the nineteenth century denounced the extension of the Factory Acts, and the enforcement of minimum standards of sanitation and of safety and care for the women and children working in the factories of the Western world.

The powerful principle of self-love and of the identity of interests when used to define social responsibilities, had results which were wholly evil. In the name of laissez faire economic individualism, employers during the nineteenth century denounced the extension of the Factory Acts, and the enforcement of minimum standards of sanitation and of safety and care for the women and children working in the factories of the Western world.

As a direct result of this new economic teaching the former state control of industry fell into disfavor. According to Eric Lipson:

Henceforth Parliament concentrated its energies upon a commercial policy which was now systematically designed to protect the interests of the producer and to ensure him the undisputed possession of the home market; it grew less concerned to control industry, regulate labor conditions and promote social stability. in accordance with the change in attitude the old industrial code was allowed gradually to fall in desuetude. The whole economic outlook of the eighteenth century was permeated by an encroaching individualism which insisted upon unfettered freedom of action … Owing to this reversal of roles, the state renounced the right to dictate to entrepreneurs, the terms on which they should employ their workfolk, and it exhibited an increasing disposition to tolerate their claims to make their own contract regarding the rates of remuneration, the length of service, the quality and supply of labor, and the nature of the products … Once the state abdicated its authority the relations of capital and labor entered a fresh stage and ceased to be subject to the rule of law. Instead of the general conditions of employment being controlled by a superior power, they were determined according to the respective strength of the opposing sides.9

The waning control of the state over industry had its counterpart in the fate which overtook the craft guilds. For centuries the latter had enshrined the principle that industry should be regulated by corporate bodies, and that no one should pursue a skilled occupation who was not a member of one of these bodies. As such the guilds were societal structures which embraced the whole of the individual's life. They were represented in local government, functioned as a private economically qualified trade union, provided contingents to the local militia, and even went so far as to regulate their own police services, festivities, and funerals and kept their own altars in churches.

Membership in such guilds was made legally obligatory, each man being enjoined to belong to some craft whose decisions carried legal status. They owned property and could settle disputes among their members, dealt with questions of hours, wages, quality of workmanship, and apprenticeships. Of these guilds and manors Tannenbaum says:

Membership in a guild, manorial estate, or village protected man throughout his life … The life of man was a nearly unified whole. Being a member of an integrated society protected and raised the dignity of the individual, and gave each person his own special role. Each man, each act, was part of a total life drama, the plot of which was known and in which the part allotted to each was prescribed. No one was isolated or abandoned. His individuality and his ambitions were fulfilled within the customary law that ruled the community to which he belonged.10

In other words, in this precapitalist order everyone had tended to enjoy his own specific "place" and society had tended to be based upon status rather than contract. It might be only a humble place, but it was recognized, and conferred rights as well as duties – rights of communal grazing, for example, and the right of the aged to support within the family, or sometimes from the village or the guild. Most workers earned only part of their keep in cash. They had real income from animals, vegetable plots, or in foodstuffs in exchange for skills (cobbler, carpenter, wheelwright) to help ensure subsistence. Above all, labor was not allowed to be sold as a commodity. As Karl Marx pointed out in Das Kapital:

The guilds of the middle ages tried to prevent by force the transformation of the master of a trade into a capitalist, by limiting the number of labourers that could be employed by one master within a very small maximum.11

Such a restriction prevented the guild master from changing to a capitalistic entrepreneur. He could only employ workmen in the same craft in which he was himself a master. The merchant could buy every commodity, but he could not buy labor as a "commodity." He was concerned only with the turnover process of the products of the trade.

If an external circumstance made a further division of labor necessary, then the existing guilds would split or form new ones beside the old. But all this took place without the merging of different crafts within the same workshop. The guild organization thus excluded, as Marx correctly pointed out, every type of the division of labor which separated the laborer from his means of production and therefore prevented the means of production coming under the sole control of the supplier of capital.

All this changed fundamentally with the coming of large scale factory production. The factory took away the workers' status and put everything upon a money basis; with wages a man could exist; without wages he starved. Children under the new capitalistic organization might be able to earn more than adults; and thus became economically more important than their parents, who either lived on them or starved. Worse still, human labor itself became a commodity along with other commodities in the general process of production and exchange. As Disraeli observed, "Modern society acknowledges no neighbour."

As a result of this industrialization of society, new class distinctions began to appear between the new factory workers in the cities and the owners of the means of production, with the former becoming reduced to "merchandise."

As a result of this industrialization of society, new class distinctions began to appear between the new factory workers in the cities and the owners of the means of production, with the former becoming reduced to "merchandise."

An iron necessity seemed to control these developments. Already, David Ricardo, the great systematizer of the classical school of economics founded by Adam Smith, had established in his Principles of Political Economy that the new machines and the workers coexist in a state of constant competition with each other. As the opening to his chapter "On Wages" Ricardo states:

Labour, like all things bought and sold and which may increase or decrease in quantity, has its natural and its market value. The natural price is that price which is necessary to enable labourers, one with another to subsist and to perpetuate their race without either increase or diminution.12

He goes on to consider how this natural price of labor asserts itself in given circumstances. In the natural advance of society the wages of labor will have a tendency to fall; as population increases, the necessaries will be constantly rising in price because more labor will be necessary to produce them.

As for profits, they had a "natural tendency to fall, for, in the progress of society and wealth, the additional quantity of food required is obtained by the sacrifice of more and more labour."13 Ricardo accepted the opposition between the workers and the capitalists as a fact. The landlord's share passed inexorably to him. It increased with population. The other two classes fought over what was left. The conditions of conflict were stringent: the national product was invariant and the money which facilitated its distribution was stable in quantity and velocity. Since the landlord's share rose, Ricardo's next proposition had the force of inevitability: "There can be no rise in the value of labour without a fall of profits." In this grim system, "in every case, agricultural, as well as manufacturing profits are lowered by a rise in the price of raw products, if it be accompanied by a rise in wages." The fall of profits diminished the incentive to accumulation of capital. When accumulation slowed, the wages fund shrank and the lot of the worker deteriorated.14

Thus when Karl Marx arrived upon the scene he already found most of the ingredients with which to concoct his witches' brew of revolution and upheaval. Marx's economics bore the imprint of Smith's labor theory of value, and Ricardo's theory of class struggle. Although he reduced the major economic classes to two by eliminating the landlords, Marx borrowed a good deal from Ricardo's handling of distribution. Starting with Ricardo's growing doubts about the favorable impact of machinery upon the working class, Marx developed a tremendous indictment of technology in a capitalist society. Marx united the wish for action with the wish for explanation. His philosophy of society is thus at once a claim to be a scientific analysis of society in the tradition of the French sociologists such as Saint Simon and August Comte and a call for a revolution to change society. As Raymond Aron well puts it in Main Currents in Sociological Thought:

If it is clearly understood that the centre of Marx's thought is his assertion of the antagonistic character of the capitalist system, then it is immediately apparent why it is impossible to separate the analyst of capitalism from the prophet of socialism or, again, the sociologist from the man of action; for to show the antagonistic character of the capitalist system irresistibly leads to predicting the self-destruction of capitalism and thence to urging men to contribute something to the fulfilment of this prearranged destiny.15

In his important study, Marxism, George Lichtheim takes issue with such an interpretation. He writes:

On this reading, Marxism is both a theory of the industrial revolution in its European phase, and an ideology of the socialist movement during the struggle for democracy. While plausible enough so far as it goes, this interpretation falls short of explaining what it was that made Marxism the instrument of total revolution and reconstruction on Russian (though not on German) soil. In particular it overlooks the fact that modern capitalism revolutionised European society only after it had been extensively secularized, i.e., placed on a rational foundation. Late medieval and Renaissance economic development effected nothing of the kind; while as late as the seventeenth century, the "bourgeois revolution" in England was intermingled with a religious struggle which was certainly more than a sham. It was only in the late eighteenth-century that the dissolution of the traditional religious world-view gave rise to modern secularism, and it was then that the French Revolution proclaimed a totally new conception of politics as the application of rational principles to human affairs. This breakthrough has determined the entire history of nineteenth century Europe, and placed its stamp upon liberalism and socialism alike. These two movements, for all their antithetical views of society, are ideological twins; they arise almost simultaneously from the intellectual crisis at the opening of the century. At first liberalism, through its association with the now briefly triumphant middle class, is better able to exploit the forces unleashed by the industrial revolution; later it is overtaken by socialism which fastens upon the revolt of the proletariat. But the two strains are intermingled from the start, and nowhere more so than in Marxism, which affirms the fulfilment of the common humanist programme.16

Marx saw what a totally secularized, urbanized, and "rationalized" capitalist society was doing to the workers who labored in its new factories and mills. Instead of blaming the rootless secularism which was dehumanizing Western civilization, and man's apostasy from God, which had taken place in the French Revolution, he blamed capitalism's division of labor and exploitation of the workers. Refusing to be ordered in his thinking by God's Word, he was forced to absolutize one aspect of human life, namely, production, and then attempt to explain everything else in terms of it. Every aspect of man's life was viewed by Marx through his economic spectacles. Instead of placing the responsibility for the capitalists' inhumanity to their fellow men where it belongs, namely, in the inherent antinomies of apostate secular humanism and the societal relations that became based upon it, Marx proclaimed that capitalist relations of production as such are the sole cause of man's alienation and estrangement. Of this deeper apostate religious motivation of Marx's thought Dooyeweerd has written:

Marx saw what a totally secularized, urbanized, and "rationalized" capitalist society was doing to the workers who labored in its new factories and mills. Instead of blaming the rootless secularism which was dehumanizing Western civilization, and man's apostasy from God, which had taken place in the French Revolution, he blamed capitalism's division of labor and exploitation of the workers. Refusing to be ordered in his thinking by God's Word, he was forced to absolutize one aspect of human life, namely, production, and then attempt to explain everything else in terms of it. Every aspect of man's life was viewed by Marx through his economic spectacles. Instead of placing the responsibility for the capitalists' inhumanity to their fellow men where it belongs, namely, in the inherent antinomies of apostate secular humanism and the societal relations that became based upon it, Marx proclaimed that capitalist relations of production as such are the sole cause of man's alienation and estrangement. Of this deeper apostate religious motivation of Marx's thought Dooyeweerd has written:

Since Rousseau and Kant religious primacy had been ascribed to the motive of freedom. But now the religious dialectic again led Humanistic thought to the acceptance of the primacy of the nature-motive. Freedom idealism began to collapse. Marxist sociology transformed the idealistic dialectic of Hegel into a historical materialism. The latter explained the ideological-super structure of society in terms of a reflection of the economic mode of production…17

The basic error of Marxism is not that it assumes a historical-economic substructure of aesthetic life, justice, morals and faith. But it separates this conception from the cosmic order of meaning-aspects, and assumes it can explain the aesthetic conceptions and those of justice, morals and faith in terms of an ideological reflection of a system of economic production.18

In the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx summarized his sociological conception as a whole:

The general conclusion at which I arrived and which, once obtained, served to guide me in my studies, may be summarized as follows. In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society – the real foundation on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come into conflict with the existing relations of production, or – what is but a legal expression for the same thing – with the property relations within which they had been at work. From forms of development of the forces of production, these relations turn into their fetters. Then comes the period of social revolution. With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such transformation the distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic – in short ideological – forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out…

In broad outlines we can designate the Asiatic, the ancient, the feudal and the modern bourgeois methods of production as so many epochs in the progress of the economic formation of society. The bourgeois relations of production are the last antagonistic form of the social process of production – antagonistic not in the sense of individual antagonism, but of one arising from conditions surrounding the life of individuals in society; at the same time the productive forces developing in the womb of bourgeois society create the material conditions for the solution of that antagonism. This social formation constitutes, therefore, the closing chapter of the prehistoric stage of human society.19

This passage contains all the essential ideas of Marx's economic interpretation of history, with the sole exception, which we should note, that neither the concept of class nor the concept of class struggle figures in it explicitly.

According to Marx we can best follow the movement of history by analyzing the structures of societies, the forces of production, and the relations of production, and not by basing our interpretation on men's ways of thinking about themselves. There are social relations which impose themselves on individuals exclusive of their preferences, and an understanding of the historical process depends on our awareness of the supra-individual social relations. Again, in every society there can be distinguished the economic infrastructure and the superstructure, the former consists of the relations of production, while the latter of the legal and political institutions as well as religions, ideologies, and philosophies.

b) The Communist Manifesto←⤒🔗

In The Communist Manifesto Marx added to the above analysis of society a coherent theory of social change in terms of the idea of the class struggle. "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles."20 In modern times Marx detected two such struggles – the struggle between feudalism and the bourgeoise, ending in the victorious bourgeoisie revolution in Britain in 1689 and in France in 1789, and the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat destined to end in the victorious proletarian revolution. In the first struggle a nascent proletariat is mobilized by the bourgeoisie in support of its own aims, but is incapable of pursuing independent aims of its own; "every victory so obtained is a victory for the bourgeoisie." Thus every step the bourgeoisie has taken so far has advanced politically until today it has obtained complete mastery over society making use of the state as its "executive committee."

The Manifesto emphasizes the revolutionary part the bourgeoisie has played in history in its relentless drive to make the "cash nexus" the only bond between men. They have dissolved all other freedoms for the one freedom which gives them command of the world market – freedom of trade. As a result the only tie it has left between man and man is self-interest and "callous cash payment." It lives by exploitation, and its unresting search for markets means an unending and profound change in every aspect of life. It gives a "cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country." It compels the breakdown of national isolation; as it builds an interdependent material universe, so it draws as a common fund upon science and learning from every nation. It means the centralization of government, the supremacy of town over country, the dependence of backward peoples upon those with more advanced methods of production in their hands.

The Manifesto describes with savage eloquence how the development of bourgeois society makes the workman a wage-slave exploited by the capitalist. The latter spares neither age nor sex. He makes it increasingly impossible for the small producer to compete with him; on every side economic power is increasingly concentrated and the little man, in every category of industry and agriculture, is driven into the dependent condition of the working class. By improving and increasing the means of production the bourgeoisie has not only created the instrument that will bring about its own death, but it has called into being the men who will wield these weapons – the modern working class.

The Manifesto describes with savage eloquence how the development of bourgeois society makes the workman a wage-slave exploited by the capitalist. The latter spares neither age nor sex. He makes it increasingly impossible for the small producer to compete with him; on every side economic power is increasingly concentrated and the little man, in every category of industry and agriculture, is driven into the dependent condition of the working class. By improving and increasing the means of production the bourgeoisie has not only created the instrument that will bring about its own death, but it has called into being the men who will wield these weapons – the modern working class.

The proletariat develops at the same rate as the capital development of the bourgeoisie They are the modern working class "who live only as long as they find work and who find work only as long as their labour increases capital."21

As industry has developed, the proletariat has also grown in number and become concentrated in great masses of population living in the new industrial cities and towns. As their wage keeps fluctuating because of improvements made in the instruments of production, and as they are subjected to ever more severe forms of exploitation, the result is that in sheer self-defense the workers are compelled to fight their masters. They form unions, ever more wide, which come at last to fight together as a class. They fight for guaranteed wages but are successful only occasionally. "The real fruits of their battle, lie not in the immediate results, but in the ever expanding union of workers."22 If the battle sways backwards and forwards, with gains here and losses there, the consolidation of the workers as a class hostile to their exploiters has one special feature which distinguishes it from all previous struggles between rulers and ruled: the working class becomes increasingly self-conscious as a class. If at first it struggles within the framework of the national state, it soon becomes evident that this struggle is but one act in a vast international drama. A time comes in the history of capitalism when its existence is no longer compatible with society. It cannot feed its slaves. It drives them to revolution in which a proletarian victory is inevitable.

According to the Manifesto the bourgeoisie by its very nature must fall. The working class upon whom it is dependent for its own existence will eventually be denied conditions under which it can exist. Every form of society has been based on the struggle between the oppressor and the oppressed. But in order for such a condition to continue the oppressor has to prevent the slave from sinking into such a state that he has to feed him instead of being fed by him. "The modern labourer, instead of rising with the progress of industry, sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class."23 The result is poverty which develops far more rapidly than population or wealth. Thus it becomes evident that the bourgeoisie can no longer be the ruling class in society because "it is incompetent to assure to its slaves their slavery."24 The existence of the bourgeoisie is dependent on the formation and increase of capital, capital on wage labor, and wage labor on competition between laborers for employment. Modern industry drives the laborers to combine into one class, thus digging the grave for the bourgeoisie.

In this second, more fundamental struggle of history between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat Marx recognizes the presence of a lower middle class – the small manufacturer and shopkeeper, the artisan, the peasant – which plays a fluctuating role between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and a "slum proletariat" which is liable to "sell itself to reactionary forces."25 But these complications do not seriously affect the ordered simplicity of the main pattern of revolution.

The proletariat is in fact the only truly revolutionary class of all the classes opposing the bourgeoisie. Since they experience the same type of submission and exploitation in all lands they have been stripped of all national character. "Law, morality, religion, are to him so many bourgeois prejudices, behind which … lurk in ambush … just as many bourgeoisie interests."26 As the working class comes to power so it will have to destroy all "previous securities for and insurances of individual property."27 The proletariat is therefore a movement in the interest of the immense majority which cannot raise itself up. The class struggle of capitalism will be replaced by "an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all."28

The pattern of revolution described in the Manifesto had been framed in the light of Marx's reading in modern English and French history, the works of French and British economists of the so-called classical school, and of Engel's study of factory conditions in England. The English bourgeois revolution, winning its victory in the seventeenth century, had fully consolidated itself by 1832. The French bourgeois revolution, more suddenly and dramatically triumphant after 1789, had succumbed to reaction only to re-emerge once more in 1830. In both countries the first revolutionary struggle of the modern age, the struggle between feudalism and bourgeoisie was virtually over; the stage was set for the second struggle, between bourgeoisie and proletariat.

The pattern of revolution described in the Manifesto had been framed in the light of Marx's reading in modern English and French history, the works of French and British economists of the so-called classical school, and of Engel's study of factory conditions in England. The English bourgeois revolution, winning its victory in the seventeenth century, had fully consolidated itself by 1832. The French bourgeois revolution, more suddenly and dramatically triumphant after 1789, had succumbed to reaction only to re-emerge once more in 1830. In both countries the first revolutionary struggle of the modern age, the struggle between feudalism and bourgeoisie was virtually over; the stage was set for the second struggle, between bourgeoisie and proletariat.

The events of 1848, coming hard on the heels of the Manifesto, did much to confirm its diagnosis and nothing to refute it. In England the collapse of Chartism was a setback which none the less marked a stage in the consolidation of a class-conscious workers' movement. In France the proletariat marched shoulder to shoulder with the bourgeoisie in February, 1848, as the Manifesto had said it would, so long as the aim was to consolidate and extend the bourgeois revolution. But once the proletariat raised its own banner of social revolution, the line was crossed. Bourgeoisie and proletariat, allies until the bourgeois revolution had been completed and made secure, were now divided on opposite sides of the barricades by the call for proletarian revolution.

The first revolutionary struggle was thus over; the second was impending. In Paris, in the June days of 1848, Cavaignac saved the bourgeoisie and staved off the proletarian revolution by massacring, executing, and transporting the class-conscious workers. The pattern of the Communist Manifesto had been precisely followed. As L. Namier, who was no Marxist, put it: "The working classes touched off, and the middle classes cashed in on it."

The June revolution (as Marx wrote at the time) for the first time split the whole of society into two hostile camps – east and west Paris. The unity of the February revolution no longer exists. The February fighters are now warring against each other – something that has never happened before; the former indifference has vanished and every man capable of bearing arms is fighting on one side or other of the barricades.29

The events of February and June, 1848, had provided a classic illustration of the great gulf fixed between the bourgeois and proletarian revolutions.

According to Marx the proletarian revolution would be led by the Communist Party, which would act as the revolutionary vanguard. As such the new program of International Communism stood for: (1) the overthrow of capitalism, (2) the abolition of private property, (3) the elimination of the bourgeois family and the replacement of home education by social education, (4) the abolition of all classes, (5) the overthrow of all existing governments, and (6) the establishment of a communist order with communal ownership of property in a classless, stateless society.30 To accomplish this program the Communist Manifesto announced that the Communists would have to change all traditional ideas in religion and philosophy. Since it puts human experience upon a new basis, it will be forced to change the ideas which are their expression. Concluding it stated:

The Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things … They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to to lose but their chains. THEY HAVE A WORLD TO WIN. WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!31

The overwhelming impression which the Communist Manifesto leaves on the reader's mind is not so much that the proletarian revolution is desirable (that, like the injustice of capitalism in Das Kapital, is taken for granted as something not requiring argument), but that the revolution is inevitable. For successive generations of Marxists the Manifesto has not been a plea for revolution – that they do not need – but a scientific prediction about the way in which the revolution would inevitably happen combined with a prescription for the action required to make it happen.

The reason for this conviction is the Marxist dogma of "Economic Determinism," that is, man's effort to survive. Communists are convinced as a matter of religious faith that everything men do – whether it is organizing a government, establishing laws, supporting a particular moral code, or practicing a particular religion – is merely the result of their desire to protect whatever mode of production they are currently using to secure the necessities of life. Further, Communists believe that if some revolutionary force changes the mode of production, the dominant class will immediately set about to create a different type of society designed to protect the new economic order. Thus the Manifesto says:

Does it require deep intuition to comprehend that man's ideas, views and conception, in one word, man's consciousness, changes with every change in the conditions of material existence? … What else does the history of ideas prove than that intellectual production changes in character in proportion as material production is changed?32

In the Handbook on Marxism we read:

It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence but, on the contrary, it is their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of their development the material productive resources of society come into contradiction with the existing productive relationships, or, what is but the legal expression of these, with the property relations within which they had moved before. From forms of the development of the productive forces, these relationships are transformed into their fetters. Then an epoch of social revolution opens. With the change in the economic foundation the whole vast superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such revolutions it is necessary always to distinguish between the material revolution in the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with scientific accuracy, and the juridical, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic – in a word, ideological forms wherein men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out.33

The essence of Marx's teaching is its claim to have a scientific character. It arose by reaction from the "utopianism" of the early socialists, who constructed ideal socialist societies out of the wealth and ingenuity of their own fertile imaginations and did not consider it necessary to concern themselves with the question how these ideal societies of the future were to be evolved out of existing societies. Marx's method was fundamentally historical; all changes in the destiny and organization of mankind were part of an ever flowing historical process. He made the basic assumption that society would in the long run always organize itself in such a way as to make the most effective use of its productive resources. He started from an analysis of existing society in order to show that the capitalist order, once instrumental in releasing and fostering an unprecedented expansion of the productive forces of mankind, had now reached a stage in its historical development where it had become a hindrance to the most effective use of these forces. It was therefore bound, in compliance with Marx's initial postulate of economic determinism, to yield place to a new social order which would once more permit and promote the maximum use of productive resources.

This new order was "socialism" or "communism" (which he distinguished in his later writings as the initial and final phases of the society to come). Marx's conception was thus both scientific and revolutionary. Most of his writings were directed not to convince his readers that the change from capitalism to socialism was desirable, but to convince them that it was inevitable – though given his original postulate, the two conceptions were implicitly identical. His conception was revolutionary in the sense that he believed that the change required by the replacement of the bourgeoisie by the proletariat as ruling class could only be accomplished by revolutionary violence. His conception was scientific in the sense that he carried to theoretical completion the unification of the previously separated sciences of politics and economics. What Marx had done was to merge both politics and economics in the new science of sociology, a term which he does not seem to have used, but which Auguste Comte invented in his life time. According to Marxists, politics and economics are ultimately a matter of the structure of society, which is in turn a result of the relations between men set up by current methods of production. The tragedy is that Marx should have chosen the economic aspect of human life as the ordering principle of the social sciences. The whole philosophy, religion, and morality of communism today is characterized by this absolutization of the economic aspect of life. As Engels states it: "The final causes of all social changes and political revolution are to be sought, not in man's brains, not in man's insight into eternal truth and justice … but in the economics of each particular epoch." Instead of defining man in terms of his relation to the God who had created him, Marxists identify man's life with his toolmaking capacity and his socio-economic functions. As Marxists see him man is not to be understood as homo religiosus as the Bible teaches but as homo economicus. Instead of believing that man is a sinner in need of redemption from the guilt and power of his sin by the death of Christ, Marxists ascribe all the wrong that men do to factors beyond their voluntary control.  They blame the existence of evil upon the existence of private property. It is for this reason that both Marx and Engels advocated a change in the economic structure of human society as the only way by which men could save themselves. Only by abolishing the right of the capitalist to control the means of production and to live off the "surplus value" of the workers' labor can the workers of the world become truly free. Out of the capitalists' control of the means of production had blossomed class struggle, greed, pride, imperialism, and war.

They blame the existence of evil upon the existence of private property. It is for this reason that both Marx and Engels advocated a change in the economic structure of human society as the only way by which men could save themselves. Only by abolishing the right of the capitalist to control the means of production and to live off the "surplus value" of the workers' labor can the workers of the world become truly free. Out of the capitalists' control of the means of production had blossomed class struggle, greed, pride, imperialism, and war.

As such communism should be thought as a substitute religion for Christianity. Instead of finding its ultimate security and salvation in God, communism finds it in withdrawing the means of production from the control of individual owners. From that alone it expects salvation to come; in that it finds its ultimate certainty in this world. For when private property and private ownership of the means of production have gone, then, says communism, war will be abolished, and righteousness and peace will prevail upon the earth as never before, and the exploitation of the workers will cease. In their opinion this climax to world history is inevitable, since it rests upon two fundamental laws which Marxists claim to have discovered, namely, dialectical materialism and historical materialism.

The basic thesis of dialectical materialism is described in official communist textbooks as follows: "Matter, nature, is eternal, infinite and unlimited." That means that matter exists always and everywhere. There is nothing in the world that does not originate from matter. With this thesis, it is obvious that communism principally and absolutely denies the existence of God, the Creator of heaven and earth. According to Communists, man is not created by God, but God is created by man; the product of misconception on man's part. As Lenin explains it:

Marx said, "Religion is the opium of the people" – and this postulate is the corner stone of the whole philosophy of Marxism with regard to religion. Marxism always regarded all modern religions and churches, and every kind of religious organisation as instruments of that bourgeois reaction whose aim is to defend exploitation by stupefying the working class…

The roots of modern religion are deeply embedded in the social oppression of the working classes … "Fear created the gods." Fear of the blind force of capital – blind because its action cannot be foreseen by the masses – a force which at every step in life threatens the worker and the small business man with "sudden," "unexpected," "accidental destruction and ruin, bringing in their train beggary, pauperism, prostitution, and deaths from starvation – this is the TAP-ROOT of modern religion."34

Communists do not deny that spiritual life exists, but they insist that such spiritual life is nothing but the offshoot of matter. A thought, for example, is a spiritual thing, but it is, according to communist doctrine, the product of the brain, "generated" by matter.

Dialectical materialism teaches that this matter is not at rest but rather in ceaseless motion. Matter generates higher levels of organization of energy. It is in process toward higher stages of development. This process occurs dialectically; that means it is subject to the law of opposites. Thus electricity is characterized by a positive and negative charge. Atoms consist of protons and electrons which are unified but contradictory forces. Communists conclude that everything in existence contains two mutually incompatible and exclusive but nevertheless equally essential and indispensable parts or aspects. They suppose that this unity of opposites in nature is the thing which makes each entity auto-dynamic and provides the constant impetus for movement and change.

As Communists conceive of it, matter is in a process of movement governed by the laws of negation and of transformation, which causes it to reach higher levels of organization. Originally there was nothing but lifeless matter. By way of a dialectical process living matter developed from this. Life came into existence not as the result of any creative act by God but by chance. Here, in short, we have nothing else than the theory of evolution and the chaos cults of the ancient Near East, dressed up in dialectical clothes.35

If Communists appeal to dialectical materialism to explain the origin of nature, they turn to historical materialism to explain the development of human society. In principle Communists believe that the same laws that hold good for the total development of the world hold also for the origin and development of human society. Accordingly, human society too is shaped by a development or process determined not by any divine ordinances but by the principle of matter. For the Communist, history is not the record of God's dealings with men, but the record of the material forces of production in use at any given time. The character of every society in history has been determined by the state of material technological factors that have been utilized by given societies in the production of goods.

For example, when in a particular society the techniques available are as yet rudimentary and manual labor predominates, then, Marxists teach, a society is necessary in which private ownership of goods and persons is the rule. Such a society existed under feudalism. As soon as technology advances, however, and steam and electrical power replaces manual and water power, then society is forced to change its social structure to one of capitalism instead of feudalism.

Today, the Marxists believe, society has reached a point at which the productive forces available make it necessary to change from capitalism to communism. The latest phase in technological change requires the common rather than the private ownership of property. Under communism the state will simply wither away.

The reason for this is that Communists believe that private property had led the owners of capital to invent the state as a necessary instrument of social control of the workers. According to the Communist Manifesto, the state is "nothing more than a committee for the administration of the consolidated affairs of the bourgeois class as a whole." When the workers had become exploited to the point where there was danger of revolt, the dominant class was forced to create an organ of power to maintain "law and order," that is, a system of laws to protect the private property and advantages of the exploiting class. This new order, they teach, is the state.

Thus Engels writes in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State:

"The state, then is … simply a product of society at a certain stage of evolution. It is the confession that this society has become hopelessly divided against itself, has entangled itself in irreconcilable contradictions which it is powerless to banish." 36

Thus the state is designed to postpone the day of judgment. The government is the "instrument of power" – an unnatural appendage to society – which is created for the express purpose of protecting the privileged class and the private property it possesses from the just demands of the exploited class. Marxists teach that when the private ownership of the means of production and distribution has been abolished the state will no longer be necessary, since there will be no one left to coerce and it will therefore gradually wither away. As class distinctions based upon private property rights disappear and production has been taken over by society as a whole, the coercive necessity for the state will disappear. As Engels put it:

"The government of persons is replaced by the administration of things and the direction of the process of production."37

This whole movement towards classless society is inevitable and irrevocable, since it is guaranteed by the irrevocable law of the dialectical progress of matter. Matter must strive with ironclad necessity to generate the highest and most perfect society – the classless society of pure communism.

Under communism or the collective ownership of the means of production and exchange, the workers' labor would no longer be treated as a "commodity" to be bought and sold. That objective is the whole import behind Marx's famous theory of surplus value which has been so much criticized by twentieth century economists. Marx was determined to give back to the workers what he considered had been so unjustly taken away from them. Classical economists had set up as the norm of economic life the freely competitive market, to which each individual was supposed to bring the product of his own labor to be exchanged for equal value, and in which the freedom of exchange produces at once the greatest number of goods and services and a substantially just distribution. Against this Marx set the ideal of the planned socialist economy as "an association of free individuals who work with jointly owned means of production, and wittingly expend their several labour powers as a combined social labour power." 38 Marx's idea was a society in which production is regulated consciously to supply commodities where needed and in the quantity needed, and in which each receives according to his needs and gives according to his abilities. He writes:

Under communism or the collective ownership of the means of production and exchange, the workers' labor would no longer be treated as a "commodity" to be bought and sold. That objective is the whole import behind Marx's famous theory of surplus value which has been so much criticized by twentieth century economists. Marx was determined to give back to the workers what he considered had been so unjustly taken away from them. Classical economists had set up as the norm of economic life the freely competitive market, to which each individual was supposed to bring the product of his own labor to be exchanged for equal value, and in which the freedom of exchange produces at once the greatest number of goods and services and a substantially just distribution. Against this Marx set the ideal of the planned socialist economy as "an association of free individuals who work with jointly owned means of production, and wittingly expend their several labour powers as a combined social labour power." 38 Marx's idea was a society in which production is regulated consciously to supply commodities where needed and in the quantity needed, and in which each receives according to his needs and gives according to his abilities. He writes:

Only when production will be under the conscious and prearranged control of society, will society establish a direct relation between the quantity of social labour time employed in the production of definite articles and the quantity of the demand of society for them.39

Thus the true productive unit is society itself, the "collective laborer works belongs to the capitalist, and a bourgeois economics division of labor. But the mechanism with which the collective laborer works belongs to the capitalist, and a bourgeois economics construes the increased productivity gained by cooperation as the productivity of capital rather than labor. Marx's economics tried to construe it in terms of human relations instead of cash nexus. Under the conditions that exist these relationships are, for the worker, stultifying and depersonalizing. The perfection of the collective worker is purchased at the cost of narrowing specialization in its parts, the individual workers. As Marx puts it:

It (manufacture) transforms the worker into a cripple, a monster, by forcing him to develop some highly specialized dexterity at the cost of a world of productive impulses and faculties. … To begin with, the worker sells his labour power to capital because he himself lacks the material means requisite for the production of a commodity. But now his individual labour power actually re-renounces work unless it is sold to capital.40

This result Marx believed to be at once an instrument of exploitation and a necessary stage in economic development. The coexistence of socialized production and capitalistic appropriation is the underlying contradiction which drives contemporary society toward the association of free individuals and the classless society of the future.

In Marxian economics the distribution of wealth is really a question of social policy to be adjusted to the requirements of production, and any adjustment is compatible with the system if it does not give rise to differences of economic class.

Both Marx and Engels envisaged a transition period between the revolution which would usher in the final socialist society and communism when the state would disappear. This they called the dictatorship of the proletariat, in which the working classes would be led by the Communist Party in destroying the existing bourgeois control and ownership of the means of production, convert these means of production into public ownership, and eventually bring in the classless society. For Communists the voice of the Party is in fact the voice of God, just as for the Jesuits the voice of the pope is the voice of God.

c) The Marxist Concept of Trade Unions←⤒🔗

For this reason Engels and Marx regarded the trade unions as promoters of treason to the revolution that would usher in the perfect society of communism. To them every bargain between capitalist owner and trade union was a betrayal of their hope of social warfare. Instead of accepting industrial discord and strife between management and unions as indicative of a natural movement for remedial adjustment, Marxists choose to escape from the requisite conflicts by abolishing the industrial system in which they arise. Communist revolutionaries suppose that if they can only be freed from these particular irritations and disputes, they will escape from all of them. For Marx the great aim was a world in which such irritations and disagreements will never again arise. Refusing to accept the biblical truth that sin resides in the human heart rather than in outward institutions as Christ most clearly taught when he said: "From inside, out of a man's heart, come evil thoughts, acts of fornicating, of theft, murder, adultery, ruthless greed, and malice, fraud, indecency, envy, slander, arrogance and folly; these evil things, come from the inside and they defile the man" (Mark 7:14-23); the Communists instead see evil to reside in institutions. By refusing to overthrow the capitalistic order of production the trade unions were standing in the way of Marx's coming Utopia, and therefore the trade unions had either to be captured and taken over so that they would serve the cause of revolution, or they had to be destroyed. To the Marxists the trade unions' effort to retrieve the older system of guilds or to reform the new was obstructionist. The acceptance of the world here and now by the trade unions Marx and Engels found especially galling. To them the trade union leader was a "petty bourgeois," a "misleader," and a "traitor." The trade union stood in the path and blocked the way to the communist heaven on earth.

Ever since Marx's time Communists and socialists have always tended to consider themselves superior to the trade unionists, and their parties were conceived as standing outside and as acting on the trade unions from above. The Communist Party is to lead and inspire the workers' movement so that in due course they join in the coming class revolution. Communists even today are so sure of their ends, so certain of the inevitability of their objectives, that the labor leader who opposes their meddling is condemned as an enemy of the working class.

The Communists will raise up the working class by creating the dictatorship of the proletariat. In Russia, therefore, which is the model of all revolutionary movements and Communist Party objectives, "not one important political or organizational question is decided by any state institution in our republic without the governing instruction of the central committee of the party."41

The trade unions have to be captured because, as Marx taught, "the general tendency of capitalist production is not to raise but to sink the average standard of wages."42 Trade unions are a misguided and wasted effort because "they are fighting with the effects but not with the cause of those effects … They are applying palliatives, not curing the remedy." Trade unions must aim at the larger goal which Marx defines as "the abolition of the wage system."43 This theme runs through Marx's writing whenever he touches on the trade unions.

Engels shared Marx's view. The trade unions are not sufficient for the purpose of the revolution. He said that "something more is needed than trade unions and strikes to break the power of the ruling class."44

In 1879 Engels criticized the English trade union movement because it had devoted its energies to the "strike for wages and shorter working hours … as an end in itself." The remedy for this preoccupation with the practical and the immediate was to "work inside of them to form within this still quite plastic mass a core of people … who will take over the leadership … when the … impending breakup of the present 'order' takes place."45

This was Engels' prescription for the American Knights of Labor, and the idea of "boring from within" and capturing the leadership of the labor unions has been applied by both Communists and Socialists wherever they could. They are still doing it, and have been doing it in America since the 1930's. By the end of the 1930's Communists controlled twenty-one of the international unions affiliated with the CIO. Similarly, the E.T.U. was found in Britain to have been infiltrated and then taken over by the Communists. In Canada the Communists took control of the International Sea Farers Union. In Italy they control nearly half the trade unions. For the Communist, then, the trade union is not important as a method of collective bargaining and hence of providing strength to the workers in their bargaining with management, but only as a political and economic tool to further the revolution.

This was Engels' prescription for the American Knights of Labor, and the idea of "boring from within" and capturing the leadership of the labor unions has been applied by both Communists and Socialists wherever they could. They are still doing it, and have been doing it in America since the 1930's. By the end of the 1930's Communists controlled twenty-one of the international unions affiliated with the CIO. Similarly, the E.T.U. was found in Britain to have been infiltrated and then taken over by the Communists. In Canada the Communists took control of the International Sea Farers Union. In Italy they control nearly half the trade unions. For the Communist, then, the trade union is not important as a method of collective bargaining and hence of providing strength to the workers in their bargaining with management, but only as a political and economic tool to further the revolution.

Such a view of the labor unions was taken over by Lenin and elaborated into a working technique. In 1900 he declared, "Isolated from Social-Democracy, the labor movement becomes petty and inevitably becomes bourgeois; in conducting only the economic struggle, the working class loses its political independence; it becomes the tail of the other parties and runs counter to the great slogan: 'The emancipation of the workers must be the task of the workers themselves.'"46

It is just this, of course, that the Communists have prevented first in Russia and wherever else they have seized power. As the dictatorship of the proletariat has developed and functioned under dictators Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev, the trade unions have been first captured by the Communist Party and used, and then emasculated of all independence of action. The workers' organizations in Russia have no other use or power than that which fits in with the political and revolutionary aims of the Communist Party. In Russia the trade unions function as organs of the Communist Government by means of which it maintains an iron control of the workers. Under Soviet Communism the labor unions do not plead the cause of the workers before the employer, but they plead the cause of the Great Employer – the state – before the employees.

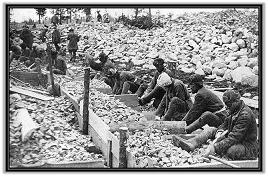

d) The Soviet Treatment of Labor in Russia←⤒🔗

Under Stalin the state directed labor. Industrial businesses signed contracts with the collective farms, by which the latter were obliged to send, if necessary by force, specified numbers of men and women to work in the great new factories that were going up in the towns and cities.

A great deal is today known about this forced labor in the Soviet Union from former prisoners now living in the West, and from Soviet writers such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn, about the ritual of arrest, confession, and sentence, and about the life of prisoners and camp organization. It is known that there were four major waves of mass arrests: the "dekulakisation" of the early 1930's, directed against recalcitrant peasants, particularly the better-off kulaks or "tight-fists"; the Yezhov terror of 1936-38, involving army officers, party officials, scientists, and business managers; the deportation of middle-class people from the Baltic states and other newly annexed areas in 1940 and 1941; and the post-1945 arrests of ex-prisoners of war and of people from the occupied areas. In addition, a more or less continuous process of arrest provided a kind of groundswell; throughout the Stalin period citizens from national minorities were particularly liable to arrest; and the ordinary worker might find himself behind the wire as a result of indiscipline or indiscretion – in the early 1950's it was possible to get five years for drunkenness.

How many people were confined in such forced labor camps? Estimates have varied from less than one and a half million to more than seven million forced laborers within the borders of the U.S.S.R. Dr. Jasny reached a figure of three and a half million, but his critics claimed that this estimate could be reduced or much increased without doing violence to the figures of the 1941 NKVD Plan. In his book, Forced Labour and Economic Development, S. Swianiewicz has suggested that figure of seven million is more probable. As a former forced laborer in Soviet Russia, Swianiewicz has tried to answer questions such as how did this terrible system arise, what was its rationale, and what function did it play in the Soviet system as a whole?47

His explanation of the emergence of the system during the first five-year plan and its perpetuation in the late 1930's and 1940's is Marxist. Given the predominance of the idea of what the author terms "explosive planning," it followed that incomes in the expanding industrial sector must rise more rapidly that the supply of industrial consumer goods and agricultural products, which were receiving less priority. From this arose "the perils of the wages-goods gap." According to Swianiewicz the introduction of forced labor had two results advantageous to the industrialization process. First it mobilized peasants into industrial and building labor at a time when they were not prepared to leave their villages voluntarily. Stalin aimed at securing by decree of the state the reserve of manpower for industry which in Western countries had been created by the chronic and spontaneous flight of impoverished peasants to the towns. Secondly, depressing the standard of living of the prisoners helped to reduce the demand for scarce food and consumer goods.

This explanation surely needs more evidence to support it. Were the authorities who ordered the expulsion of the kulaks motivated by the need for cheap labor rather than by their wish to break the opposition of the peasantry to collectivization? Isaac Deutscher in his classic work on Stalin answers that it was both. He says:

Rapid industrialization at once created an acute shortage of labour, and that meant the end of laissez faire. This was, in Stalin's words, the "end of spontaneity" on the labour market, the beginning of what, in English speaking countries, was later called the direction of labour. The forms of direction were manifold…

Forced labour, in the strict sense, was imposed on peasants who had resorted to violence in resisting collectivization. They were treated like criminals … As the number of rebellious peasants grew, they were organized into mammoth labour camps and employed in the building of canals and railways, in timber felling and so on. "Re-education" degenerated into slave labour, terribly wasteful of human life.48

When Swianiewicz tries to account for the perpetuation of this system of forced labor into the later 1930's and beyond he is more illuminating. In his account, the driving mechanism at this stage was combination of scarcity of manpower with the inability of the government to direct labor and to organize the labor market. The scarcity of manpower was due to the fact that most unproductive labor had already been removed from the villages. The inability of the government to direct labor was due not to a belief in freedom but to "the lack of disposition in the population to cooperate with authority." Here Swianiewicz contrasts the social experience of Russia where "the peoples of what is at present the Soviet Union passed neither through the school of democratic citizenship nor through that of trade unionism," with that of Western Europe, which has "produced not only the individualism of the capitalistic entrepreneur but a disposition for cooperation in matters concerning the national community." He might also have pointed out that the workers of the Protestant nations had also learned a dedication for work sadly lacking in Orthodox lands. As Max Weber well said, "The Puritans wanted to be businessmen; we are condemned to it." The worker in Soviet Russia is condemned to fulfill a narrow social function within vast and anonymous groups, without the possibility of a total flowering of the personality which was possible in Puritan society. However, we can accept his conclusion that legislation controlling the movement of labor was less effective in the U.S.S.R than in Britain during the war. The forced labor system of Soviet communism thus becomes, on Swianiewicz's hypothesis, a very large periphery to the free labor market, and serves to adjust the distribution of labor to the priorities of government.

To explain is not to justify. Swianiewicz seeks to show that even considered purely in economic terms the cost of maintaining the machinery of coercion was so great that no net gain to the government may have resulted. However, he neglects to point out the disciplinary advantages which the known existence of the labor camps must have produced in the free labor sector of the Russian economy.

To explain is not to justify. Swianiewicz seeks to show that even considered purely in economic terms the cost of maintaining the machinery of coercion was so great that no net gain to the government may have resulted. However, he neglects to point out the disciplinary advantages which the known existence of the labor camps must have produced in the free labor sector of the Russian economy.