The Elder as Preserver and Nurturer of Life in the Covenant: What the Bible Says

The Elder as Preserver and Nurturer of Life in the Covenant: What the Bible Says

⤒🔗

⤒🔗

Introduction←⤒🔗

A characteristic of churches in the Reformed and Presbyterian tradition is surely that the office of elder is dear to all of us. Indeed, there is good reason for statements such as that of G.D. Henderson: "The eldership is perhaps the most distinctive feature of those Churches of the Reformation which honour the Calvinistic tradition."1 It would appear that if our coming together as churches in the ICRC is to be as beneficial as possible, basic issues like the office of elder, should be discussed for our mutual edification. The church cannot really function and flourish without a vibrant exercising of this office. The combination of our different heritages and our common purpose suggests that it would be profitable to start to consider this office in the ecumenical context of this conference in order that we may benefit from each other's insights as influenced by our different histories.

The purpose of this introductory paper is therefore to stimulate further discussion about this office with the hope that the result may be not only a renewed appreciation and love for this office, but also a deeper insight into how we regard the eldership, so that the functioning of this office may be as fruitful as possible in the churches.

To this end let us first survey the biblical data and see the basic task of this office, namely, to be God's servants and instruments to stimulate and preserve the life with God in the covenant community and so to labour for the rule of Christ and His Word in the church. Next, let us briefly look at the development of this office in the subsequent history of the church and, finally, to bring the matter into a practical focus, pose two questions for further consideration.

The Old Testament Background←⤒🔗

The office of elder in the New Testament cannot be understood without first considering the background of this office in the Old Testament and intertestamental times. It is, however, especially the Old Testament that should be carefully considered. The fact that this background is sometimes hardly acknowledged can lead to an insufficient appreciation of what this office entails.

The Hebrew term for "elder" derives from a noun meaning beard. Etymologically it thus basically refers to a man with a beard. The term practically always refers to old men or to the elders as officials. We are interested in the latter usage. We do not read anywhere of the origin of this office (which as such was also well-known outside Israel, e.g., Genesis 50:7) and it may be assumed that it has developed from the tribal structure of Israel. An elder was probably a head of a family or tribe. Presumably after his death, his oldest son would take his place. However, if he was incompetent, then it could go to a younger son. The point is that to be an elder involved recognition by others, not only because of one's age as well as one's legal position, but also in view of one's gifts, one's authority and ability to lead and, if necessary, to represent the interests and wishes of the people. The basic criterion of age, inherent in the term for elder, was important because it carried connotations of wisdom and experience associated with older age (Deuteronomy 32:7; cf. Psalm 37:25; 1 Kings 12:6-8, 13). The elders, therefore, commanded respect and could be expected to know the history of God's people (Deuteronomy 32:7; Lamentations 4:16; 5:12).

t is an intriguing question how exactly the eiders were organized in the nation of Israel. However, for our purposes this point can be bypassed for the most part. Suffice it to note for now that elders functioned on a national level as elders of the people (e.g., Exodus 3:16), on a tribal level as elders of a particular tribe (e.g., Judges 11:5), and locally as elders of a city (e.g., Judges 8:14). What especially concerns us now are the key duties that the eiders in Israel had. These can be summarized as: first, the task of judging and discipline generally, and second, the task of ruling and guiding the people and the affairs of the nation in an orderly way. It is especially through these responsibilities that the elders were instrumental in preserving the life with God in the covenant community. It is no accident that these same two major elements also essentially constitute the task of the elders in our congregations today.

It is remarkable that in the early history of Israel as a nation we read three times of the special appointment of elders; twice specifically for judging, and once for ruling. In Exodus 18:24-26 we read that Moses appointed what were apparently elders (heads of tribes, cf. Deuteronomy 1:15) to act as judges in the relatively simple matters of justice so that he could concentrate on the more difficult ones. It has been suggested (by W.H. Gispen) that Moses herewith perhaps restored them as elders to their former office. So important was this action that it receives a prominent place at the beginning of Deuteronomy, where we are told (Deuteronomy 1:13) that Moses had said to the people: "Choose wise, understanding, and experienced men, according to your tribes, and I will appoint them as your heads" (these are the judges of v. 16), and the people agreed (v. 14). Notice how the congregation of Israel was involved. With the appointment of the judges to help him, the normal functioning of justice became an attainable goal while Israel lived in the wilderness. At the same time it prepared God's people for a clear recognition of the importance of maintaining righteousness and justice also later in Canaan.

The command to appoint judges in Canaan as recorded in Deuteronomy 16 is a further development. "You shall appoint judges and officers in all your towns (lit. 'gates') which the LORD your God gives you, according to your tribes" (Deuteronomy 16:18). This command is addressed to the people; so once again they are involved in the appointing of judges, although we are not told how. Whereas during the wilderness wanderings the people all lived around the tabernacle, in Canaan they will spread out in the different towns and cities, and the local town or city gate becomes the place where God's law is upheld (by the elders of the city). In effect, there is a certain decentralization here (a principle dear to us in Reformed church polity). If, however, a case was too difficult, then (according to Deuteronomy 17) "you shall arise and go up to the place which the LORD your God will choose, and coming to the Levitical priests, and to the judge who is in office in those days, you shall consult them, and they shall declare to you the decision" (Deuteronomy 17:8b, 9). There was thus a higher tribunal, which however did not function as a court of appeal. It was for cases too difficult (cf. also Deuteronomy 19:17). This reminds one of the place of Moses (in Exodus 18), who dealt with the difficult cases. With the coming of the office of king in Israel, the function of the chief judge fell to him (cf. 1 Samuel 8:5, 20, where Israel asks for a king to judge them (RSV "govern"), 2 Samuel 15:2-4; Psalm 72). As such a godly king could be expected to have a keen interest in the maintenance of justice in the land (2 Chronicles 19:8-11).2

We also read of elders being appointed by Moses on the command of the LORD in order that Moses might have help with ruling the people. We read in Numbers 11:

And the LORD said to Moses, 'Gather for me seventy men of the elders of Israel, whom you know to be the elders of the people and officers over them; and bring them to the tent of meeting … and I will take some of the Spirit who is upon you and put Him upon them; and they shall bear the burden of the people with you, that you may not bear it yourself alone' (vv. 16-17).

These men are clearly different from those appointed by Moses in Exodus 18 to help in executing justice.

Elders remained involved with the rule of God's people subsequent to the time of Moses, whether government was decentralized as in the period of judges or more centralized as Israel moved toward a theocratic monarchy. In accordance with their office, they exercised God's rule over the people on behalf of God Himself. The LORD made this rule possible by entrusting to them, along with the Levites, the care of His law and will, as well as the duty of imprinting this law on the hearts and minds of His people. We read in Deuteronomy 31 that Moses, after writing the law, "gave it to the priests the sons of Levi, who carried the ark of the covenant of the LORD, and to all the elders of Israel." Then follows the command that this law be read to the people at the end of every seven years at the feast of booths (Deuteronomy 31:9-13). The elders had a special responsibility to see to it that Israel knew the law and lived by it. Together with Moses they commanded the people to keep the law in Deuteronomy 27:1 and they were summoned first by Moses before he delivered his final song (Deuteronomy 31:28), for they had a specific obligation to make sure that Israel would know its contents. Indeed, Moses told Israel in his final song that Israel should ask their fathers and the elders for instruction in the history of God's dealing with His people (Deuteronomy 32:7). The weight of the office is also seen in Joshua 24:31, where we read: "And Israel served the LORD all the days of Joshua, and all the days of the elders who outlived Joshua and had known all the work which the LORD did for Israel" (similarly Judges 2:7). The implication is that the elders led Israel in the ways of the LORD. So the elders' rule of Israel included that crucial obligation of placing the demands of the great King of Israel, the LORD God, before the people. This made possible their guiding Israel in the ways of the covenant.

Now the task of ruling belonged to the elders from earliest times. Hence, in order that Moses' leadership over Israel might be recognized, the LORD instructed Moses to gather the elders of Israel together and their present, so to speak, his credentials; namely, that the God of their fathers had sent him to them because God was going to deliver them (Exodus 3:13-18). If the elders recognized his leadership, so would the people. This aspect of the ruling task of the elder continued after the time of Moses. During the period of the judges, the elders of Gilead saw to it that Jephthah became their leader to meet the threat of the Ammonites (Judges 11:4-11). It was also the elders who asked Samuel for a king (1 Samuel 8:4-5). The important place of the elders is later underlined in the words of Saul after Samuel told him that God had taken the kingdom away from him. Then Saul acknowledged his sin and said: "Yet honour me now before the elders of my people" (1 Samuel 15:30). With respect to David's kingship, the elders of Israel anointed him king over all Israel (2 Samuel 5:3; 1 Chronicles 11:3; cf. 2 Samuel 3:17-18; cf. also the presence of the elders in.2 Samuel 17:1-4).

With this type of involvement in leading and ruling the nation, it is to be expected that the elders would also serve with their counsel and advice. Sometimes their advice was bad, as in the days of Eli, when they decided to send the ark into battle (1 Samuel 4:3). Generally, however, they could be expected to give good advice, and wise counsel became associated with the elder (cf. Ezekiel 7:26 and Jeremiah 18:18).

In summary, elders were to be able men who feared God and were trustworthy (Exodus 18:21, 25), wise, understanding, and experienced (Deuteronomy 1:13) and who were enabled by God with His Spirit (Numbers 11:16, 17) to carry out their vital tasks of judging and ruling. The people were involved in placing elders in their office, and the authority of the elders was recognized. Their primary responsibility, however, was to God, for their task of judging and ruling was to be in accordance with God's law. Indeed, the latter task even included their having responsibility for imprinting the law of God in the hearts and minds of the people (Deuteronomy 31:9-13). In this way they were to serve God and the people and work for the preservation and development of the life with the LORD in the covenant community.

Transition←⤒🔗

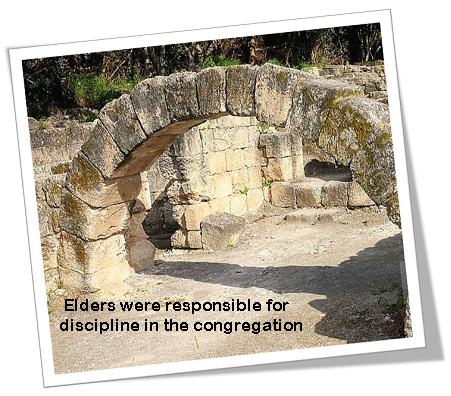

Although the period after the exile through to New Testament times was one of profound change, the office of elder basically stayed intact. On the national scale, with the effective dissolution of tribal units, the individual families grew in importance, and elders from the resulting nobility had the leadership. By the beginning of the second century B.C. there is evidence of the existence of "a council of elders" consisting of 70 (71) members, the Sanhedrin. At first the members were generally spoken of as presbyteroi, "elders." However, the term was used more and more to distinguish the "lay" members, who probably came from the patrician families in Jerusalem, from those with a priestly lineage as well as (after c. 70 B.C.) those drawn from the ranks of scribes. This situation is reflected in the New Testament. The system of local elders continued (Ezra 10:7-17), and each Jewish community had its council of elders associated with the synagogue (cf. Luke 7:3), an institution generally dated from Ezra or during the exile. These elders were responsible for discipline in the congregation (cf. Matthew 10:17; John 9:22). It is this local eldership that is of particular importance for our topic, for it retained the essential features of the Old Testament office of elder and it lay behind the office of elder in the Christian church. This brings us to the New Testament elder.

The New Testament Elder←⤒🔗

For our purposes the first thing that needs to be noted is that the first Christians were Jewish and that the office of elder was well-known to them from the synagogue. For that reason Luke can mention Christian elders for the first time in Acts 11:30 (regarding Jerusalem) without any need for explanation. The office was a familiar one, known also from what Luke had written earlier. On their first missionary journey Paul and Barnabas appointed elders in every church (Acts 14:23). The verb used for "appoint" leaves open the possibility that the congregation participated in the process. Paul also charged Titus to do the same in Crete (Titus 1:5). This office belonged to the local congregation (cf. also Acts 20:17; James 5:14; 1 Peter 5:1).

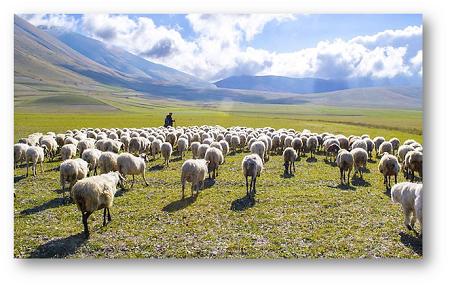

In the second place, in the New Testament elders (presbyteroi) are also called bishops (episkopoi, in e.g., Acts 20:28), and, by implication, "shepherds," without implying any essential difference in the office referred to.3 To be sure, the apostle Paul does distinguish between those elders who rule well, especially those who labour in the preaching and teaching (1 Timothy 5:17), whom we generally call ministers of the Word, and others. However, common to all elders is the task of oversight and discipline of the congregation as well as the responsibility to rule and guide the people of God with the Word in a manner that is pleasing to God. In other words, the task of the elders (not including all the implications of the specific mandate of the ministers of the Word) is basically the same as that of their Old Testament predecessors; that is, also elders in the new dispensation are to preserve and nurture life with God in the covenant community. They may do so in the service of the risen Lord and are enabled by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

Coming to specifics, we note that the elders' task of oversight and discipline is described in various ways in the New Testament. Some examples: in bidding farewell to the Ephesians elders the apostle Paul said:

Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers to care for the church of God which He obtained with the blood of His own Son.Acts 20:28

Peter wrote: "So I exhort the elders among you as a fellow elder … tend the flock of God that is your charge, not by constraint but willingly, not for shameful gain but eagerly, not as domineering over those in your charge but being examples to the flock. And when the chief Shepherd is manifested you will obtain the unfading crown of glory." 1 Peter 5:1-2

The pastoral and ministering nature of their oversight and discipline is obvious. They have to watch over souls (Hebrews 13:17) and protect and nurture life with God in the covenant community. This may mean correction and admonition (1 Thessalonians 5:12; cf. Acts 20:31), and, if there is no repentance, it may eventually lead to excommunication (Matthew 18:17; 1 Corinthians 5:13; Titus 3:10).

As far as the elders' task of ruling and guiding the congregation is concerned, it is clear from the New Testament that they have been set over the congregation in the Lord (1 Thessalonians 5:17). They rule (1 Timothy 5:17). The elder is also called a steward of God (Titus 1:7). The term "steward" literally indicates that the elder is a manager of God's household. However, the figurative meaning probably is uppermost here, meaning that the elder is an administrator of spiritual treasures (cf. 1 Corinthians 4:1; Matthew 13:11, 52). This says something about the nature of the elder's position of authority. Uppermost in the ruling of the congregation is to be the administration of the glad tidings. Therefore false doctrine must be opposed and the truth safeguarded (Acts 20:28, 31; Titus 1:9-11). For that reason, like their Old Testament counterparts, elders have the responsibility to see to it that the gospel and the demands of the Lord are imprinted in the hearts and lives of God's people (cf. 1 Thessalonians 2:11, 12; 2 Timothy 2:24-26).

With such responsibilities, it is no surprise that the prerequisites for the office are high. For our purposes now I would like to stress that, like his Old Testament predecessors, the elder in the last age has to command the respect of others by being blameless and God-fearing and by showing in his walk of life the fruits of the Spirit (1 Timothy 3:2-4,7; Titus 1:6-9; cf. Galatians 5:22-23). He also has to be able to teach others the way of the Lord (1 Timothy 3:2; cf. 5:17). As Paul wrote Titus: "He must hold firm to the sure Word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to confute those who contradict it." Titus 1:9

Although the office of elder is not in the first place a teaching but a ruling office, yet a good knowledge of the Word of God was essential. They needed to know it! Think of the crucial role of the elders in Acts 15:1-6, who with the apostles had to make far-reaching decisions. This knowledge of the Word and the ability to teach others also had to be accompanied by a mature sensibility, so that the elder would not be quarrelsome (1 Timothy 3:3) or enter senseless controversies (cf. 1 Timothy 1:3; 6:4-5).

All these requirements suggest that elders were to be chosen very carefully after they have clearly proven themselves and shown themselves endowed with the necessary gifts. If Jewish tradition and indirect biblical data are heeded, then a candidate for an elder must be at least 30 years of age. There are no direct biblical data informing us how long an elder is to serve. The Old Testament background of the office would, however, strongly suggest that the eldership is a lifelong office. There is also nothing in the New Testament to suggest otherwise. Indeed, it could be argued that the high requirements of the office would seem to indicate that it may not be easy to find suitable candidates for the office and that therefore the church will not too readily let go of good office-bearers.

The Decline and Recovery of the Eldership←⤒🔗

In spite of the long and illustrious history of the office of elder, the office was eventually taken up in the priesthood in what became the Roman Catholic church. It was not until the time of the Reformation that this office came into its own again.

The story of how the office of elder was rediscovered is an intriguing one, but lies outside the scope of this presentation. Suffice it to say that it was especially under Calvin (who could build on the work of Oecolampadius and Martin Bucer) that a true Biblical insight into the office could be had. However, it should also be mentioned that Calvin himself apparently never came to a fully consistent and clearly focused Scriptural exposition of the office of elder. This had consequences for the churches of the Reformation.

What should have our attention now is how we can learn from each other with a view to this office, keeping in mind the brief review of Biblical data that has earlier had our attention. There is much food for thought in discussing the eldership as Reformed and Presbyterian confessors. However, since this is but an introductory paper, let us start modestly and consider two very basic and probably related issues, namely, the preparation for the office and the length of service.

Special Training for the Office?←⤒🔗

In view of the high demands of the office, should elders receive some type of special training as preparation for the office? This matter is not a new one within the history of the Reformed churches. Already in the seventeenth century Jakobus Koeleman argued for such a training on the ground of 1 Timothy 3:10 so that the churches would receive competent and knowledgeable elders. The Rev. Dr. A.C. van Raalte in 1839 gave lessons to elders and deacons. Also, in the Classis Apeldoorn it was for a long time the custom to make inquiries about the Bible knowledge of elders and deacons. In 1913 Prof. L. Lindeboom defended the necessity of a separate training for the elders. His reason was basically that the many duties required of the elder demanded it. Dr. H. Bouwman, however, opposed him.4 As reasons he adduced that,

-

First, the Reformed character of the office would be threatened, for a new type of clergy could be the end result.

-

Secondly, if elders are only chosen from people specially educated for the office, then many will be bypassed.

-

Thirdly, not scientific instruction, but the practical training received in the catechism class, in the Bible study societies, and in their own investigation of the Scriptures is important.

-

Fourthly, the more modest and better qualified would not participate.

-

Fifthly, not all would support such an institution of training and it would thus be doomed to failure.

-

Sixthly, it would promote life-long eldership.

-

Seventhly, the admonition of Paul in 1 Timothy 3:10 that the deacons be tested in the first place refers to practical life experience, not to an academic examination.

Experience has taught many a pastor that these counter-arguments of Dr. Bouwman are not all to the point. It is the elders themselves who usually ask why there is not some sort of training (and training within an institute is usually not envisaged). Such questions are raised in the awareness of the burden and importance of the office of elder. Should not every effort be made to have elders who are as well prepared as possible? It has been suggested that although there is no explicit Scriptural demand for any special training for the elder, yet, the fact that "teaching elders" (ministers) are given an extensive and detailed training does suggest that something is amiss when "ruling elders" receive none whatsoever. Their tasks, although differentiated, have much in common. They are both called elders in the Scripture (cf. 1 Timothy 5:17) and they both labour with the Word. Could such a training be implemented and at the same time take into account some of the concerns of Dr, Bouwman?

Let me pass on the suggestions of Lawrence R. Eyres, who as an Orthodox Presbyterian minister wrestled with this issue.

-

First, there should be a return to the practice of encouraging and grooming young men for possible leadership. It is important that churches recognize gifted men.

-

Secondly, these men need some sort of training. Of great importance is a good grasp of doctrine and how that arises out of Scripture. Knowledge of church government is also important.

-

Thirdly, there should be training in ministering the Word. After all, an elder is a co-shepherd with the pastor. A good manual would go a long way here.

-

Fourthly, elders-elect should be tested in the areas mentioned above before they are ordained.5

The above list of suggestions is not an isolated phenomenon in the Presbyterian world and it has several attractive elements.

To be sure, not all Presbyterians have some form of training. The Free Church of Scotland, for example, does not appear to have anything in place. On the other hand, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church specifies in the 1980 edition of their The Form of Government that one is normally eligible for election to the office only after he has – received appropriate training under the direction of or with the approval of the session, and shall have served the church in functions requiring responsible leadership. Men of ability and piety in the congregation shall be encouraged by the session to prepare themselves for the offices of ruling elder or deacon so that their study and opportunities for service may be provided for in a systematic and orderly way.6

A specific example may illustrate how such a preparation has been provided. An elder ordained in a Canadian Presbyterian church related to me how he initially was interviewed (in effect, examined) by his Session to determine his interest and desire in being ordained as a ruling elder (1 Timothy 3:1; 5:22). Only when the elders were satisfied and he understood the responsibilities of eldership and had the necessary qualifications for the office, was he told to prepare himself for a preordination examination (Titus 1:5-9; 1 Timothy 3:2-7). Such preparation could involve being trained formally by the minister. The three-hour examination was open to the congregation and covered Bible knowledge, Old and New Testament exegesis, Reformed doctrine, Church History, and Pastoral Care. The only difference from an examination of a minister ("teaching elder") was that Biblical languages were omitted and there was no sermon proposal. Also congregation members were able to ask questions if they so desired. After a successful examination the congregation voted him as elder.7 Such or similar procedures strike me as doing justice to the great importance of the office of elder and would go a long way to meeting some of the concerns that many new elders now voice. Furthermore, it avoids some of the concerns Bouwman raised over against a more institutionalized form of training. Should those who generally speaking have given little thought to the training of elders prior to their election and ordination (like the Canadian Reformed Churches8) not start thinking of how we could help in the equipping of men for this very important but demanding office that Christ has given His church? After all, the bottom line is that the life with God be nurtured as well as possible by the effective ministration of the full covenant Word.

Length of Service←⤒🔗

A second point is the length of service. Among those with both Presbyterian and Reformed backgrounds, this matter can be discussed in the realization that our specific histories exhibit both possibilities, namely life service or term eldership. Calvin was apparently in favour of term eldership (of one year), but he did not exclude the possibility of a longer time period. In his Ecclesiastical Ordinances of 1541 Calvin wrote:

And at the end of the year after their election by the Council they (i.e. the elders) shall present themselves to the Seigneury so that it may be decided whether they should be retained or replaced, though, so long as they are fulfilling their duties faithfully, it will be inexpedient to replace them frequently without good cause.

In Scotland, The First Book of Discipline (1560) reflects Calvin's view. In the Eighth Head (Touching the Election of Elders and Deacons) we read:

The election of Elders and Deacons ought to be used every year once … lest of long continuance of such officers men presume upon the liberty of the kirk. It hurteth not that one be received in office more years than one, so that he be appointed yearly by common and free election." Here we see one of the primary motives for a yearly election; namely, the fear that some by virtue of their office may "presume upon (i.e. usurp) the liberty of the kirk.

This was not an idle threat, for, somewhat like the way in Geneva elders were chosen from civil councils, in Scotland elders were initially taken from the Lords of the Congregation and the Burgh Councilors.

When the Second Book of Discipline was adopted in 1578, the office of elder was recognized as a permanent one (although all did not need to serve simultaneously or continuously) and thus, rather than being appointed annually, they now entered the office for life. This was reaffirmed by the Act of the General Assembly of 1582. However, "it took some time for the impact of these acts of the Assembly to take effect, as there is evidence of annual elections of elders continuing to take place, while in 1656 it was still believed that 'the order and practice' of the Church was regular elections."9 As late as 1705 an overture was presented to General Assembly asking that new elections for elders be for a four-year term. Other evidence suggests that "the eldership was regarded as an annual office till the beginning of the eighteenth century."10 It is clear; however, that lifetime eldership was the official norm and as far as I know that is still the case in the Presbyterian churches associated with the ICRC.

In the Reformed Churches, life eldership was known; but, eventually all elders had a limited term of office. Elders were chosen for life in the Reformed congregations in sixteenth-century London and Cologne. Questions were raised about the practice among the Dutch refugee congregations in England. A conference held in 1560 dealt (among other items) also with this point. It was decided to maintain life eldership for the following reasons, given here in summarized form.

-

First, there is an essential unity of the office of minister of the Word and elder. The ministers are called elders and the elders are called bishops or shepherds (1 Peter 5:1; Acts 20:28).

-

Secondly, those who served faithfully as elders or deacons were not removed from their office but were placed in the ministry of the Word, as Stephen and Philip were (cf. Acts 6:8-14; 21:8). Only Nicolaus is removed from his office, but then due to unfaithfulness (Revelation 2:15).

-

Thirdly, the office is not temporary, for Paul exhorts the elders of Ephesus to take heed to themselves and to the flock without indicating how long they should serve. They are told to persevere.

-

Fourthly, on a more practical level, from the fact that some elders had to leave the office in order to be able to provide for their families does not follow that it is profitable to have term eldership. As apprentices in normal life are trained for a long period of work in which experience becomes an important asset, so also the congregation is not served by having constantly new office-bearers. On a more practical level, the influence of hierarchical tendencies in the Church of England have been seen as important factors in the maintaining of lifetime eldership in the Dutch churches there.11

Also in the Netherlands, the practice of life eldership was not unknown. In North Holland, it was known until 1587 (possibly due to a lack of candidates). Also, it is of interest to note that the "provinciale synode" of Utrecht declared in 1612 that it was desirable for elders to be chosen for life although it recognized that this was no longer possible and thus accepted the established practice of term eldership. However, in the province of Groningen elders were chosen for life until the end of the eighteenth century.

Nevertheless, already very early in the history of the Reformed churches in the Netherlands, namely, at the meeting in Wezel in 1568 and three years later at a synod in Emden, the idea of term eldership was strongly supported for practical reasons and became the accepted norm within the churches. Thus the reason for a restricted period of service for elders, as given at Wezel already, is that it is too heavy a burden and thus impacts negatively on their normal employment or business. This reason must be seen in the context of the persecution of those days. The Synod of Dordrecht 1578 also gave this as the chief reason (and it allowed for exceptions). However, that practical consideration was not the only reason. In requested advice to the Synod of Middelburg 1581, Professor L. Danaeus of Leiden gave as reasons for term eldership the following:

-

First, Scripture does not demand life eldership;

-

Secondly, lifetime eldership can lead to ecclesiastical tyranny;

-

Thirdly, with term eldership more people can have an opportunity to get involved in the government of the church; and,

-

Fourthly, term eldership is now a general practice although, if desired, one can deviate from it.

Some Recent Discussion on Length of Service←⤒🔗

The issue of whether the length of office should be for life or not has been discussed in recent decades in both Presbyterian and Reformed circles. In 1955 John Murray felt it necessary to publish a strong article in favour of lifetime eldership when the Form of Government in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church was being revised and a proposal had been made contending for term eldership.12 After making clear that an elder can still be removed from or relieved of the office for a number of reasons, Murray gives the following Scriptural arguments.

First, "there is no overt warrant from the New Testament for what we call 'term eldership'" (p. 352). Murray goes on to argue that inferences drawn from the New Testament militate against the practice. "The permanency of the gifts which qualify for the office and the judgments of the church that Christ is calling this man to the exercise of the office" (p. 354) are inconsistent with a limited term, all the more when one considers that the gifts increase in fruitfulness and effectiveness with their use in time. Finally, there is "the unity of the office of ruling. In respect of ruling in the church of God. the ruling elder and the teaching elder are on complete parity" (p. 354). If there is no term office for the one, why should there be for the other? Murray even goes on to say that "one cannot but feel that the practice of term eldership for ruling elders is but a hangover of an unwholesome clericalism which has failed to recognize the basic unity of the office of elder and, particularly, the complete parity of all eiders in the matter of government" (p. 355).

Over against the argument that the minister of the Word makes this calling his life work, whereas the ruling elder does not, Murray responds, first, that this does not invalidate the permanency of the call to the office of elder; second, with respect to 1 Timothy 5:17-18, that the ruling elder can be remunerated on a part-time as well as fulltime basis, and, third, that also the ruling elder is worthy of his hire.

Coming now to a discussion held in Canadian Reformed circles in 1974, we note that the Rev. W. Huizinga was asked (presumably by an office-bearers' conference) "to evaluate Scriptural data concerning the periodic retirement of elders and deacons (ad art. 27, C.O.), keeping in mind the historical developments in the Reformed churches in this matter." He concluded on the basis of the Old Testament evidence that "whenever the LORD appointed or had someone appointed to an office the office-bearer usually served for life unless the character of the office itself required only a short-term office-bearer. Only unfaithfulness is found as a reason for dismissal from office, for example, in the case of Saul."13 As far as the New Testament evidence is concerned, he concluded that "the New Testament evidence gives us the IMPRESSION that elders and deacons were installed for life" (p. 5). The evidence brought forward dealt,

-

First, with the continuity of the Old and New Testament office bearers.

-

Secondly, with the seriousness of the office (Acts 14:23; 1 Timothy 5:22). Once in office, the elder would stay an elder.

-

Thirdly, some passages clearly give the impression of a life-long calling.

For example, does aspiring to the office (cf. 1 Timothy 3:1), imply life-long service or only a few years? Acts 20:28 indicates that the Holy Spirit made the elders overseers of the flock. "Would the Holy Spirit say, for example, after three years, now you are no longer needed? You may go and I will call you again if I need you? Would this not be like a licensed tradesman saying to his apprentice, whom he has trained at great costs to himself: all right, you can go back home now and do your regular old job full-time again? Is this appointment by the Holy Spirit not easier to explain if we presuppose long-term instead of short-term eldership?" (p. 4). Rev. Huizinga then reiterated the arguments of the London congregation at the 1560 conference. His final conclusion is, however, that it is still questionable and debatable whether we should be forced to abandon the Reformed custom of periodically retiring and replacing elders and deacons (p. 5).

The well-known H, Bouwman, in his work Gereformeerd kerkrecht, vol. 1 (pp. 607-608), stated summarily that although the New Testament gives the impression of office for life, yet those Reformed churches that were influenced by Calvin have decided on term eldership in order to avoid hierarchy and to increase the influence of the congregation on the government of the church. Further, one should not forget that the distinction between the teaching and the ruling elder was just starting to take shape in the first century.

It would seem to me that the arguments from Scripture for life eldership significantly outweigh those of term eldership. Obviously, there has been no unanimity on this matter in the history of the church and it thus seems unlikely to come about now. Another factor important within the context of this introduction is what would serve the congregation best. It would be good if our Presbyterian brothers could later address this matter from their own experience for our mutual edification.

Conclusion←⤒🔗

The eldership of course includes many more issues than have been raised here. However, with respect to what has been broached in this introduction, it would appear that the office of elder merits continued study and stimulation in the church. The importance of this office is difficult to overestimate. All through the history of God's people the elders were used by the Lord as His instruments to stimulate and work for the preservation of the life with God in covenant holiness and faithfulness. Meetings of the International Conference of Reformed Churches should never forget this gift of our Lord Jesus Christ to His church and so lose touch with the daily concerns of the local congregation. The differences that exist among us in precisely how this office functions in the church can serve as a positive stimulant to considering this office again for the mutual benefit of us all.

Add new comment