The Reformers: John Wycliffe

The Reformers: John Wycliffe

It is hoped, God willing, to go through the lives of some of the great reformers such as Wycliffe, Huss, Luther, Calvin and Knox and their successors. The aim is to show who were the founders of Protestantism, what they taught, and what was their main contribution to the progress of the Protestant Reformation in Europe, especially in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. The emphasis, therefore, will not necessarily be on their lives but on their teaching. It must be remembered that this teaching was like a light against a dark background, the background of medieval Catholic error. At the same time it is not intended to emphasize their attack on the corrupt system, so much as their spreading of the truth in the pure gospel. And the first Reformer to be mentioned is John Wycliffe.

Wycliffe's work consisted of more than the translation of the Bible from Latin to English. It was essentially a break with the Roman Catholic faith. This was not entirely realised by the Catholic Church until after his death when he was finally branded as a heretic, because unlike Luther, Wycliffe was not excommunicated in his lifetime. But nonetheless, he was in open revolt against the Church system in which he had been reared, and he was not a novice in understanding its affairs. In fact he became a Doctor of Theology at Oxford University. Born in Yorkshire in 1324, he was destined for the Church from an early age. Probably initially educated in a Cathedral or Monastic school, at about the age of sixteen he went to Oxford. He was first a Scholar and then Fellow of Merton College. Great scholars were in the University at the time, but the one who influenced Wycliffe most was probably Thomas Bradwardine. He had embraced the doctrines of free grace and was a Professor in the University. Most of his contemporaries treated Christianity from an academic point of view –not as Bradwardine – he accepted the truth of the Word of God and taught his students to do the same. He warned his students, against free-will and a religion which emphasised externals and ignored the teaching concerning worshipping God "in spirit and in truth." "The fame of Bradwardine's lectures filled Europe," says J. A. Wylie in his "History of Protestantism." It was from this man that Wycliffe first received the truth in its purity.

Wycliffe's work consisted of more than the translation of the Bible from Latin to English. It was essentially a break with the Roman Catholic faith. This was not entirely realised by the Catholic Church until after his death when he was finally branded as a heretic, because unlike Luther, Wycliffe was not excommunicated in his lifetime. But nonetheless, he was in open revolt against the Church system in which he had been reared, and he was not a novice in understanding its affairs. In fact he became a Doctor of Theology at Oxford University. Born in Yorkshire in 1324, he was destined for the Church from an early age. Probably initially educated in a Cathedral or Monastic school, at about the age of sixteen he went to Oxford. He was first a Scholar and then Fellow of Merton College. Great scholars were in the University at the time, but the one who influenced Wycliffe most was probably Thomas Bradwardine. He had embraced the doctrines of free grace and was a Professor in the University. Most of his contemporaries treated Christianity from an academic point of view –not as Bradwardine – he accepted the truth of the Word of God and taught his students to do the same. He warned his students, against free-will and a religion which emphasised externals and ignored the teaching concerning worshipping God "in spirit and in truth." "The fame of Bradwardine's lectures filled Europe," says J. A. Wylie in his "History of Protestantism." It was from this man that Wycliffe first received the truth in its purity.

This to Wycliffe was like a light in a dark place, because mostly, theology, or what was termed theology, in his day, consisted of discussions on the writings of such men as Peter Abelard or Thomas Aquinas, rather than a study of the Scriptures, which was considered an inferior occupation and one of less academic importance than a study of some of the free-will theologians of the Church, such as Aquinas. In the Churches up and down the country, worship was polluted by gross superstitions. In 1348, the Plague swept the country and thousands died – the fields ceased to be cultivated and in London alone it was believed that about 100,000 died. Wycliffe was about twenty-five at the time, and there is no doubt that the awful visitation in the nation and in Europe brought to him some solemn thoughts and led him to search the Scriptures to which Bradwardine had introduced him. Though little is known accurately of how the Lord called him to a saving knowledge of the truth, it would seem from his defence of the truth that he was brought to it clearly and solemnly and made to feel his need of a Saviour that could heal him, and that after the teaching of Bradwardine, the Plague might have been the turning point in his life.

From 1340-1360 he was at Merton. Then in 1360 he became Master of Balliol College. In the years at Merton as a fellow of the College, he lectured on the Bible and thus he became profoundly versed in the Scriptures, "and thus was the Professor unwittingly prepared for the great work of Reforming the Church." (Wylie). But it was not to be by expounding the Scriptures only, that Wycliffe was to gain renown. He was to act as a representative for Britain in a controversy with the Pope. This centered around the sovereign rights of the King of England and the Pope. A century before Wycliffe's birth King John had been forced by the Pope to recognise him as his feudal overlord and pay a tax each year in recognition of the English King's servility to the Pope. The Pope claimed (and still does) that he was "The King of the Kings of the earth." John a corrupt and weak monarch bowed to the Pope's threats. This act had been resented by the English barons, who far from recognising the Pope as their feudal overlord, now pressed King John for a recognition of their liberties which they obtained in the "Magna Carta" of 1215. This was deeply resented by the Pope, who looked upon the barons as his rebel subjects. But the attitude of the barons saved England from total subservience to the Pope. The tax was regularly paid for some years, until England became stronger, and then about 1330 it was quietly dropped and continued so until 1365, when a new Pope, Adrian, demanded its payment, plus arrears. The English King, Edward III, was not willing to pay, besides which, many of the English bishops were Italians who were being kept on Englishmen's tithes. To halt this foreign infiltration two Acts were passed in the English Parliament to limit the interference in the Catholic Church in England from Rome.

Parliament met in 1366 to discuss the demand of the Pope and Wycliffe was present (whether as a Member or an observer is not clear) and kept a record of the speeches. Not a voice was raised to support the Pope. All thought that King John had acted beyond his powers in giving the nation to the Pope by recognising him as his superior. The barons in Parliament felt that in the first place they were subjects of England, and only secondly members of the Roman Catholic Church. None was willing to put Church before country as the Pope wished. The question was settled – a King and not a Pope would rule in England. The Parliament said that King John had acted against his Coronation oath and given his allegiance to the Pope without Parliament's consent and so his action was null and void. This was a great step forward in "the Reformation," the repudiation by the English Parliament of the Pope's temporal claim to be "the King of the Kings of the earth." It was only a step from denying the temporal supremacy of the Pope to questioning his spiritual supremacy. The demand of a tax of a thousand marks put the theory of Papal Supremacy into practice and while Englishmen might condone it in theory, they refused to accept it in practice. Now men were ready to criticise a system whose prestige had up till then blinded them to its falsity.

Parliament met in 1366 to discuss the demand of the Pope and Wycliffe was present (whether as a Member or an observer is not clear) and kept a record of the speeches. Not a voice was raised to support the Pope. All thought that King John had acted beyond his powers in giving the nation to the Pope by recognising him as his superior. The barons in Parliament felt that in the first place they were subjects of England, and only secondly members of the Roman Catholic Church. None was willing to put Church before country as the Pope wished. The question was settled – a King and not a Pope would rule in England. The Parliament said that King John had acted against his Coronation oath and given his allegiance to the Pope without Parliament's consent and so his action was null and void. This was a great step forward in "the Reformation," the repudiation by the English Parliament of the Pope's temporal claim to be "the King of the Kings of the earth." It was only a step from denying the temporal supremacy of the Pope to questioning his spiritual supremacy. The demand of a tax of a thousand marks put the theory of Papal Supremacy into practice and while Englishmen might condone it in theory, they refused to accept it in practice. Now men were ready to criticise a system whose prestige had up till then blinded them to its falsity.

It appears clear that Wycliffe had expressed many "Reformation type" views in his lectures at Oxford and that such views had taken root and spread in the nation. His position in the controversy was a prominent one. This is clear from the fact that, when an English monk took up the cause of the Pope in writing and justified his temporal claims over the land, he challenged Wycliffe by name to disprove his reasoning. In defending the issue, Wycliffe styled himself "the King's peculiar clerk," which suggests that either he was a royal chaplain, or at least that his learning and defence of the matter had brought him to the notice of the King. Even in such a position of royal favour he was in some considerable danger, because the more completely he exposed the hollowness of the Roman Church, the more likely it was that they would retaliate, when it might take more than a King to defend his life. Wycliffe was moderate in his reply and kept to the matter under discussion – who was to have the final control in England, the King or Pope. He saw the issue as a concern of the King and nation and not merely his personal view, and showed that the issue was not between a monk and an Oxford Doctor, but between the Pope and the King of England.

All Europe watched to see whether Edward III would bow to the Pope. He did not and the victory was England's, and very much of the credit for that must go to Wycliffe. Soon after this he took his doctorate of Theology and was raised to the chair of Theology at Oxford where his influence was now extended.

From questioning the abuse of the power of the Papacy, Wycliffe came to the question the Papacy itself and examine it in the light of the Scriptures. We can have no conception of what this meant for him, as we live in an age when the hollow system has been exposed and any who accept it do so not from ignorance, but in the light of its recognised materialistic attitude to religion. To Wycliffe the system was the only accepted form of Christianity in his day and there was no other denomination to which he could turn; and it took another generation or two to come to the concept of completely breaking with the old order of the Roman Catholic Church and founding a new Protestant Church.

As Wycliffe read his Bible, he saw clearly that the Gospel and the Papacy had little to do with one another and that to follow one meant to renounce the other. His next conflict after his defence of the royal power was with the Friars. Strange he should attack men who were apparently leading a holy life of poverty and self-neglect, which might in some ways counteract the obvious worldliness and wealth of the Pope, Cardinals and Bishops, and so restore the good name of the Church. Yet such self-imposed poverty had not always lasted and the monastic orders created for this very thing had more often become just as worldly and wealthy as the rest of the Catholic Church. Long before Wycliffe's day there were abbotts who excelled princes in their power and wealth. Good food, beautiful furniture, great retinues of retainers, fine horses, hunting, etc., marked the monastic houses out for notoriety, instead of their vows of poverty and charity. The Papacy itself recognised the vast corruption of the early monastic orders and tried to remedy it by founding new ones bound to abstinence and poverty. The Franciscans were founded in 1215 and the Dominicans in 1218. St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the first movement, considered that all holiness and virtue consisted in poverty and acted out his theory to the last letter. Before he died, he had founded 2,500 convents on his ideas of poverty, and from the order there have come at least five Popes. Dominic, the founder of the second order, aimed to stamp out heresy against the Catholic Church. He saw how much the worldliness of the monks and the wealth of the Church drove men into heresy and away from the Church. So he called for a new order of monks who would preach to heretics and show by their poverty that the Church was not entirely corrupt. The order was divided into two groups – one to preach the Catholic doctrine, the other to kill obstinate heretics. Soon this small group rapidly spread like the Franciscans and both orders did immense work for the Catholic Church in the countries of Europe in the century before Wycliffe was born in 1324.

These two orders were different from other monks in that they were not confined to their monasteries, but treated them rather like hotels. They travelled and revived the lost art of preaching, mixing freely in society, especially among the poor. They stood out from the other monks in that they literally were beggars and were known as "Mendicants." Their reputation for holiness was therefore great and their influence extended among all classes. They were the advance guard of the Papacy in Europe in Wycliffe's day. Then why did he attack them? Because their practice changed and they soon became as wealthy as the old orders such as the Benedictines and Augustinians. Still wearing their coarse robes, they sold images, relics, rosaries and accepted money. They did not use it to buy land as they were forbidden to do this, but they built splendid churches and monasteries and became indolent, corrupt and insolent, making bad use of the powers conferred on them by the Popes. When Wycliffe came to examine these Friars, they were almost wholly corrupted. He first opposed them in 1360, forty years after they had first come to England. Forty houses of Dominicans were established in England in his day and were known as the Blackfriars.

These two orders were different from other monks in that they were not confined to their monasteries, but treated them rather like hotels. They travelled and revived the lost art of preaching, mixing freely in society, especially among the poor. They stood out from the other monks in that they literally were beggars and were known as "Mendicants." Their reputation for holiness was therefore great and their influence extended among all classes. They were the advance guard of the Papacy in Europe in Wycliffe's day. Then why did he attack them? Because their practice changed and they soon became as wealthy as the old orders such as the Benedictines and Augustinians. Still wearing their coarse robes, they sold images, relics, rosaries and accepted money. They did not use it to buy land as they were forbidden to do this, but they built splendid churches and monasteries and became indolent, corrupt and insolent, making bad use of the powers conferred on them by the Popes. When Wycliffe came to examine these Friars, they were almost wholly corrupted. He first opposed them in 1360, forty years after they had first come to England. Forty houses of Dominicans were established in England in his day and were known as the Blackfriars.

One of these houses was at Oxford and it was there that they attacked the University itself, claiming independence from it. This started a battle between them and the University and led to a complaint by the Oxford Chancellor to the Pope in which he said, "By the privileges granted by the Popes to the friars, great enormities do arise." Among the abuses he listed the trapping of students at the University to enter the mendicant orders from which they could never get out and went on to show how parents became afraid to send their sons to Oxford, and as a result, the University student population had declined from 30,000 to about 6,000 with a resultant decay of every branch of learning in the country. He described the friars as "a pestiferous canker." But his appeal was useless – these men were the orders created by the Popes – they were the Papal weapons to spread Catholicism, and Oxford University and its decline meant little or nothing to the Popes.

The Chancellor of Oxford, who later became Archbishop of Armagh, died in 1360, and in that very year the Lord raised up Wycliffe to continue the attack on the Friars, which he did more or less to the end of his life. He saw deeper than the late Oxford Chancellor. He did not attack abuses, but saw that the very foundation of the two orders was unscriptural and demanded the abolition of both. Their power was great. It stemmed directly from the Pope himself, and especially in their so-called ability to forgive sins, they possessed a potent weapon. Their teaching was dangerous – real religion, they said, was to obey the Pope, pray to St. Francis and give alms to the friars. This opened the gates of heaven, they taught. Religion was for them a trade. Exactly the same abuse roused Luther several generations later to promulgate his Theses – the Friar's name then was Tetzel, about whom we hope to refer, God willing, in a later article. The controversy Wycliffe aroused was excellent, as it caused men to search out the foundations of the Gospel and see from Scripture whether what he said was true. The question that was raised was, "Who can forgive sins?" Wycliffe was able to point out the Bible answer, "God only," and so the battle was between truth and error. In his Oxford lectures, Wycliffe taught that salvation was through the blood of the Lord Jesus Christ, "neither is there salvation in any other, for there is none other name under heaven, given among men, whereby we must be saved" Acts 4. 12. He published a work called "Objections to Friars" in which he charged them, with at least fifty heresies. This marks the beginning of his claim to the title of "Reformer."

In this tract he preached the Gospel rather than attacked the Friars. He said, "There cometh no pardon but of God." He spoke of "pretended confessions" and said, "There is no greater heresy than for a man to believe that he is absolved from his sins if he give money." "But all the masses of the Church, pilgrimages and giving alms will not and cannot bring a man's soul to heaven, unless he truly repent and keep God's commandments and set fully his trust in Jesus Christ." Wycliffe said, "I confess that the indulgences of the Pope, if they are what they are said to be, are a manifest blasphemy … The friars give a colour to this blasphemy by saying that Christ is omnipotent and that the Pope is his plenary vicar and so possesses in everything the same power as Christ in his humanity. Against this rude blasphemy I have elsewhere inveighed."

It was and still is, the kingpin of the Papacy, that the Pope has the right to grant pardon and dispense its operations to his agents, priests, friars, bishops, etc. Also he claims the right to exclude men from heaven by his excommunicating them from his Church. Such priestly power Wycliffe saw through, and here surely is the seed of the Reformation. It was the same supposed power that Luther was to attack. Wycliffe in attacking the Friars proclaimed the Gospel. In proclaiming the Gospel he exposed the hollow foundations of the Catholic Church.

It was and still is, the kingpin of the Papacy, that the Pope has the right to grant pardon and dispense its operations to his agents, priests, friars, bishops, etc. Also he claims the right to exclude men from heaven by his excommunicating them from his Church. Such priestly power Wycliffe saw through, and here surely is the seed of the Reformation. It was the same supposed power that Luther was to attack. Wycliffe in attacking the Friars proclaimed the Gospel. In proclaiming the Gospel he exposed the hollow foundations of the Catholic Church.

In the compass of a year's articles on the Reformers, it will not be possible to deal with every aspect of the work of each in their lives. This month we must conclude our articles on Wycliffe and will deal with two more aspects of his work – namely, his work in translating the Scriptures, and his attitude towards Transubstantiation.

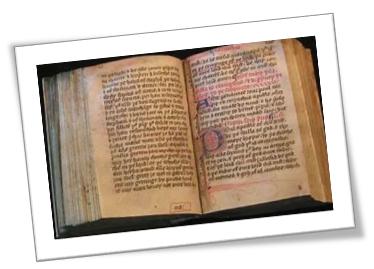

These subjects bring us towards the end of his life in the years 1380-1384. He had previously called in question the allegiance of his country to the Papacy, and attacked the weapons of the Papacy in spreading its false teaching through the agency of the Friars. But more important than this work was his share in spreading the truth to his fellow countrymen by translating the Scriptures into the mother tongue. We speak of the "Written Word," but Wycliffe's work truly was with the written word, for there was no printing presses in his day and every copy of the translated Scriptures had to be laboriously copied by hand. Wycliffe's work was to perform the original task of translating out of the Latin into English. There is doubt cast today on what amount of the work he actually did with his own pen. It has generally been accepted that he translated the New Testament himself and that another scholar, Nicholas of Hereford, did the translating of the Old Testament. But whatever doubt is cast upon the actual translation, it is clear that the master mind behind it, in the essentially "Reformation concept" of giving the Scriptures to the common people, was Wycliffe.

The year of its completion was about 1382. This was the year that Nicholas of Hereford was excommunicated by the Catholic Church for beliefs similar to Wycliffe's, and thrown into prison in Rome, when he went there to appeal against his excommunication an interesting manuscript exists, preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, with erasures and alterations, containing a note that it was the work of Nicholas of Hereford. It consists of the Old Testament in its entirety, together with a part of the Apocrypha. The unfinished nature of this manuscript fits in with the fact that Nicholas of Hereford was suddenly called away from his work to defend himself against the charge of heresy. For Wycliffe the work was being done in the evening of his life. He had only two years to live when it was completed, in which he was excluded from teaching at Oxford and which he spent in his quiet rectory at Lutterworth. As the work was revised later by his curate John Purvey, the revision being completed in about 1388, it seems likely that this was what Wycliffe spent much of the last two years of his life doing, perfecting what had already been achieved before he left Oxford.

It may be asked why Wycliffe was not persecuted to death. This was due entirely to the weakness of the Papacy after 1378, when it became divided over the election of two Popes. This had occurred, because in the election of the Pope in 1378, the Roman populace had gathered in a riotous action to force the Cardinals to elect an Italian, and later when they had left Rome, some of them gathered in the southern part of Italy and elected a Frenchman, as Pope. This circumstance was used of the Lord to spare Wycliffe from almost certain martyrdom in the last six years of his life, during which period he was working on the translation of the Scriptures. In this period he came to very clear views of their value. In a work called, "On the Truth and Meaning of Scripture," he maintains their supreme authority and insists on the right of private judgment not that they are open to the individual interpretation of any one, but that they are equally not to be interpreted by the Catholic Church alone. Two copies of this work still exist – one at Oxford in the Bodleian Library, the other in Trinity College Library, Dublin. It contains the essence of a Reformation view of Scriptures as of "supreme authority" and not to be counterbalanced by any traditions of the Church having equal authority. Wylies says of Wycliffe's translation, "What mattered it (now) when a dungeon or grave might close over him! He had kindled a light which could never be put out. He had placed in the hands of his countrymen that true Magna Carta. That which the Barons at Runnymede had wrested from King John would have been turned to but little account had not this mightier Charter come after."

The work of copying the translation was hard – but it was done and gradually men went out with Wycliffe's translation, Lollard preachers, up and down the land, stopping on village greens and other public places to read the Scripture to the illiterate people for the first time. Not until the mid-nineteenth century was Wycliffe's Bible ever printed. Recently from a bookshop in Wells, Somerset, we acquired one of these nineteenth century printed copies of a Wycliffe manuscript. The Catholic Church was horrified when she learnt what Wycliffe had done. It was rather like a civil servant revealing state secrets to the man-in-the-street. They had hoped that his work of spreading the Gospel might have died with him. Now a new work was abroad, which they could not stop, though in 1408 the English Church Council banned the reading of Wycliffe's Version to all Catholics under threat of excommunication, and also banned any further attempts at a translation into English.

The work of copying the translation was hard – but it was done and gradually men went out with Wycliffe's translation, Lollard preachers, up and down the land, stopping on village greens and other public places to read the Scripture to the illiterate people for the first time. Not until the mid-nineteenth century was Wycliffe's Bible ever printed. Recently from a bookshop in Wells, Somerset, we acquired one of these nineteenth century printed copies of a Wycliffe manuscript. The Catholic Church was horrified when she learnt what Wycliffe had done. It was rather like a civil servant revealing state secrets to the man-in-the-street. They had hoped that his work of spreading the Gospel might have died with him. Now a new work was abroad, which they could not stop, though in 1408 the English Church Council banned the reading of Wycliffe's Version to all Catholics under threat of excommunication, and also banned any further attempts at a translation into English.

With this gigantic effort accomplished, Wycliffe did not rest. He wished to see his countrymen even further freed from error. Now he turned to attack the doctrine of the Roman Church. He regarded this doctrine as the opposite of that given by Christ to His Church. He selected one dogma for attack as being the key to many errors. This was transubstantiation which claims that the bread and wine at the Lord's Supper are turned, after the priest has blessed them, into the actual body and blood of the Lord Jesus, and are offered and elevated for worship at the altar. Wycliffe saw that this was pure idolatry, as well as being the source of the prodigious authority claimed by the Roman Church. He saw the conflict as between the supposed sacrifice of a priest and the one and only sacrifice of the Lord Jesus on Calvary. He first publicly denounced the error in the spring of 1381. He posted up "Twelve Propositions" in Oxford for discussion, challenging all who disagreed to come and debate the matter. The first stated, "The consecrated Host which we see upon the altar, is neither Christ nor any part of him, but an efficacious sign of him." He maintained that the bread and wine were only figuratively the body and blood of Christ. This caused great confusion in Oxford. But no one accepted his challenge. They were all agreed that this was heresy. A Council of University doctors and monks was summoned by the Oxford University Chancellor, who unanimously condemned Wycliffe's statements as heretical. He was suspended from lecturing in the University and ordered to remain silent on his opinions under threat of imprisonment. He appealed to Parliament for redress, but as Parliament was not in session for some time, he eventually left Oxford for his parish at Lutterworth to await events.

During this period the Peasants Revolt broke out, led by Wat Tyler, which resulted in the Archbishop of Canterbury being beheaded by the rebels at the Tower of London. This had the effect of delaying the Catholic Church from pursuing its persecution of Wycliffe, until a new Archbishop was fully installed. This accomplished, at last in May 1382, the new Archbishop convened a Synod to try the Rector of Lutterworth. It met at Blackfriars Monastery in London. It was strange that hardly had the Council commenced work when London was shaken by an earthquake, which the Archbishop interpreted as an omen signifying the cleansing of the land from heresy, but which must have pointed for many of Wycliffe's followers, to the indignation of God against the Council about to try Wycliffe. The Council met for three days and condemned Wycliffe's beliefs as heretical and erroneous and sent commends to various Bishops to make certain that "these pestiferous doctrines" were not taught in their dioceses. A letter also went to Oxford University, but the views of Wycliffe were widespread there and it needed a further appeal to Richard II before the University could be brought to heel. He gave authority to imprison any who maintained Wycliffe's beliefs. As the storm increased many of Wycliffe's supporters left him. John of Gaunt, a nobleman who had been very willing to support him in his attack on the temporal claims of the Pope, withdrew when the term heresy was used by the Catholic Church. When Wycliffe's appeal came before Parliament in November, 1383, it repealed the persecuting edict of the Church against him. The Archbishop then convened Convocation to try him, and he appeared before this august Assembly of the Church to justify his beliefs, refusing to retract anything. His final words in his own defence have a beauty about them for their fearless simplicity. "You are the heretics," he said, "who affirm that the Sacrament is an accident without a subject. Why do you propagate such errors? Why? Because like the priests of Baal you want to sell your masses. With whom, think you, are you contending? With an old man on the brink of the grave? No! With Truth – Truth which is stronger than you and will overcome you." With these words he turned to leave the Assembly. His enemies had no power to stop him. "Like his Divine Master at Nazareth," says D'Aubigne, "he passed through the midst of them."

He went quietly back to Lutterworth, now a weary and sick man. During the remaining days of his life he was summoned to appear at Rome before the Pope to answer for his heresy, but he was too ill to travel. On the last Sunday of the year 1384 as he administered the Lord's Supper in his Church at Lutterworth, he was taken ill with a stroke, carried to the Rectory and died here on December 31st. His useful life was over, but a light was lighted in England which has never gone out since, though we live in a day when subtle so-called ecumenical attempts are being made to smother it under the cloak of toleration and reunion with the Papacy. Buried at Lutterworth, Wycliffe's body was disturbed in 1428 by order of the Pope, burnt and his ashes thrown into the River Swift which flows through the town. But that could not silence the Truth and it has been well said that those ashes carried by the Swift to the Avon, and by the Avon to the Ocean were a symbol of the Truth of God for which he had fearlessly contended in his life, and which has ever since gone out to the four corners of the world. Wycliffe was the Father of the Reformation – its Morning Star – the Scriptures were the sole authority for his beliefs, the Lord Jesus his one and only Master. We honour his memory as we remember him once again. Like the apostles, he has no resting place we can visit, yet his memory is indelibly written in the earth and as the Scriptures say, "The memory of the just is blessed."

He went quietly back to Lutterworth, now a weary and sick man. During the remaining days of his life he was summoned to appear at Rome before the Pope to answer for his heresy, but he was too ill to travel. On the last Sunday of the year 1384 as he administered the Lord's Supper in his Church at Lutterworth, he was taken ill with a stroke, carried to the Rectory and died here on December 31st. His useful life was over, but a light was lighted in England which has never gone out since, though we live in a day when subtle so-called ecumenical attempts are being made to smother it under the cloak of toleration and reunion with the Papacy. Buried at Lutterworth, Wycliffe's body was disturbed in 1428 by order of the Pope, burnt and his ashes thrown into the River Swift which flows through the town. But that could not silence the Truth and it has been well said that those ashes carried by the Swift to the Avon, and by the Avon to the Ocean were a symbol of the Truth of God for which he had fearlessly contended in his life, and which has ever since gone out to the four corners of the world. Wycliffe was the Father of the Reformation – its Morning Star – the Scriptures were the sole authority for his beliefs, the Lord Jesus his one and only Master. We honour his memory as we remember him once again. Like the apostles, he has no resting place we can visit, yet his memory is indelibly written in the earth and as the Scriptures say, "The memory of the just is blessed."

Add new comment