Piety – Examples from History

Piety – Examples from History

In our first article we saw how valuable piety is in the Christian life. You can ask yourself if faith without piety is real faith. When superficiality and coldness appear in the church, you always hear the call for piety, for a faith that is characterized again by trust and confidence. But that has more than once also led to excesses. We are going to look at a number of important piety movements in history.

The Pillar Saint: Elevated above the People⤒🔗

Life with God often entails separation and isolation. That is inevitable. In our secular society you can’t avoid it. But how is it in the congregation? Can also the ways of brothers and sisters divide?

There are many examples of sincere Christians who choose for separation. Just look at church history. It started already early in the Christian church. The urge for piety led hermits to withdraw from others. One could write several books about this, but let me give one example to show the risks of such an attitude.

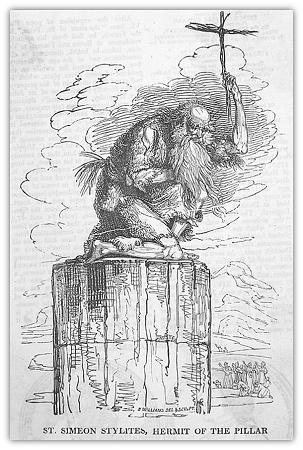

A well-known hermit in the early church is Simon the pillar saint (d. 450). That’s of course not his real surname; it became his nickname. He thinks that he can avoid sin and come closer to God by living on a pillar that is over three meters high. His willingness to sacrifice so much for a pious life brings him many admirers. But admiration by humans is the number one enemy of piety. Let us realize that first of all. And indeed, Simon moves to a still higher pillar. He does that several times, until in the end he lands on one that is some ten metres high.

From above he looks down on the masses of common people. When he is not occupied with prayer or meditation, he speaks to them in a warning tone. Every day with the help of a chord he lets down a little basket. His admirers can put bread in it and so help support his piety. Sometimes a critic puts in just a note with the words: “He who doesn’t work shall not eat.” That must of course be the work of a jealous person, for no one is as pious as Simon.

In this story we already see that piety can have a number of negative aspects, such as the idea that evil comes especially from outside, with as a result that you attempt to flee the world. But the thing I especially want to pay attention to in this story of Simon is the pillar.

Do you also sometimes have this feeling, in your own congregation? That there are people who are admired for their spiritual performance? That like Simon they sit on a pillar and that you, small and insignificant, stand below them? That your faith and your trust are so weak? That there are many things about God that you do not understand and that God sometimes seems so far away? That deep in your heart you are jealous and would love to be closer to God?

This feeling of being spiritually insignificant can easily be fed by a wrong image of piety. There are all sorts of pillar saints: some person can pray beautifully, apparently gets messages directly from God, can sing with ecstasy about his faith experiences, can witness of amazing ways in which God intervenes in his life—and there you are below the pillar, year after year, and reverently put bread in his basket.

I am thinking of the children who did not dare come to the Lord Jesus because there were so many bigger ones between him and them. You know what the Lord Jesus did. Therefore, I dare say with conviction: the pious one is not the person who sits on the pillar but who stands below the pillar!

The Monk: Piety in Isolation←⤒🔗

We go briefly back to the hermits. Their life is characterized by isolation and by abstinence, especially abstinence from meat and wine and marriage. Does piety flourish if you live a sober life and withdraw from others?

Let us listen to ex-hermit Basil. He speaks as follows of his time as a hermit. “Generally speaking, I have not accomplished much by my isolation. The life of the hermit is opposed to a life of love, for the hermit cares only for himself. Such a person will also not easily get to know his own errors and sins. He will use the gifts of the Spirit for himself only and so bury them in himself. In a life with others the gifts of the Spirit benefit them all.” Well, that is well said by someone who speaks from experience. We can learn from him if we wish to live a life of piety. Namely, that it is not to be focused on ourselves, but on the community.

Basil has acted according to his convictions and exchanged his life as a hermit for the communal life within a monastery. In that way the individualism of the life of the hermit has been overcome. But not the isolation. This they continue to seek, with as goal a life of purity and devotion to God, in groups of people who share this goal. That is how the monastic orders arise, with their own monasteries.

It is to be noted that such seeking isolation happens when there is decline in the church. In the medieval church many lived a worldly life, not only common people but also spiritual leaders. Now the tendency toward isolation is noticeable not just in the Roman Catholic church of that time. It always happens when the church becomes worldly. Then people who really wish to serve the Lord seek to join with others in small groups: in a monastery or in various other communities and “societies.” In all these cases it is always a matter of isolation within the church.

In the monastic life there is special attention for other people, apparent in various kinds of works of mercy. The monasteries are known for their care for the sick, education, care for the poor, and hospitality. That piety continued in those dark Middle Ages, which lasted for a thousand years, is especially thanks to monks and nuns who in isolation devoted their life to God.

It is well known that toward the end of the Middle Ages monastic life declined. Withdrawal from the world does not guarantee a holy life. The evil heart accompanies those entering the monastery and causes people to live in sin. The monk shows us that piety opens your eyes and heart for your neighbour, but at the same time that abstinence and self-chastisement can ask too much of a pious heart. It can even cause you to fall if in well-meant zeal for the Lord you attempt to bear greater burdens than God gives you to bear. Those who want to live a pious life must always ask themselves: am I doing this really for the Lord or for the sake of my own religious feelings?

The Mystic: The Pious Soul Merges with God←⤒🔗

Cherishing and nursing one’s own religious feelings has always been present when pious men and women seek isolation. Almost always it is combined with a disdain for the body and for what belongs to the body. The famous Francis of Assisi calls his body “brother donkey.” The body is for him a beast of burden that only serves to carry the immortal soul through this earthly existence. With this idea St. Francis comes quite close to the Greek philosophers.

We notice that the hermit Antony harbours similar ideas. He never washes himself. He wears the inside of a sheep’s fleece on his naked body. The fleece scours the dirt off his body and the wounds that are constantly caused by this scouring are a welcome torment to “suppress the lusts of the flesh.”

The well-known Benedict of Nursia overcomes the violent temptations of the flesh by rolling his naked body through thorns and thistles. When keepers of goats discover him in his cave they think at first that he is a wild animal: that’s what he looks like.

We first give attention to the concern with one’s own religious feelings. Seeking community with God can go so far that we lose sight of our human limitations. Hermits and monks obviously have not always escaped this danger. The Basil we mentioned says that often he thinks with longing of the feelings he enjoyed during his days as a hermit: “How I satisfied myself at that time with wants and hardships! Who gives back to me those night watches and songs of praise, that lifting up of my heart to God, that heavenly non-physical suffering.” About another hermit we read: “The holy man slept on a bed of dry leaves. He baked his own rye bread, grew some vegetables, kept a goat and a dozen chickens. But the hermit’s soul and all his doings were always turned to God alone. His concern, and indeed his life, was to admire and praise God in all his works, and to become submerged in seeing his unfathomable goodness.”

Those who try to rise above the world and everyday reality by sinking into the divine are no longer pious. It is a very old and at the same time a present-day danger that accompanies ecstatic religious experiences. By meditation people will achieve unity with God—and so without redemption and without the Saviour. Piety is no longer piety if we ignore the boundary between ourselves and our God. It has become paganism. Mysticism, we also call it.

The Donatist: Purity without Charity←⤒🔗

Overdoing things, trying to be overly pious, is evident not only in mysticism. It is also striking that such piety insists on an absolutely pure church. We see that already in the history of the early Christian church. Because there is a lesson for us, we will briefly talk about it.

The early Christian church suffered severe persecution during the first centuries. The Roman emperor Nero is still mentioned as a symbol of cruelty when we talk about these persecutions. In the arena Christians are thrown before the lions, they are used as living torches in the palace gardens; no torture is bad enough. Many courageously persevere and die as martyrs—both young and old. Examples are the 86-year-old leader Polycarp, the fifteen-year-old Ponticus, and the slave girl Blandina.

But there are also Christians who become afraid. They deliver their holy books and offer incense to the emperor. So they save themselves from a miserable death in the arena. But with most of them the result is remorse and shame.

This causes conflict in the church. Many refuse to allow these fallen brothers and sisters to come back into the congregation. They find that God’s church must be pure. And to become a leader or deacon—that is totally out of the question for such a backslider! The best-known zealots for a pure church are the so-called Donatists. This name derives from that of one of their leaders: Donatus. They come especially from North Africa, but these confessing Christians are highly respected also in Europe. It has become a large movement.

That movement goes far in its zeal for a pure church. If a backslider has become an office-bearer in a congregation, he is heavily criticized. His opponents refuse to accept him. If he has baptized someone, that baptism is declared invalid. In this way Donatists declare the meaning of a baptism to depend on the purity of the person who administers it.

The Donatists hold to a piety without charity. They close their hearts to people who are fearful in their faith, and weak, and seeking. They forget how the Lord Jesus accepted Peter again in mercy and established him as a worker in his church. Christians who insist on an absolutely pure church become a sect. They forget that they still live in a broken world; that they are on the way with brothers and sisters who, stumbling and falling and rising again, follow their Saviour. From the Donatists we can learn that piety without charity is not real piety.

The Pietist: He Who Desires to Live Piously…←⤒🔗

She was called Pia, a girl with me in class. “You know that you have a lovely name,” the teacher said that first day when he noted our names. “It means piety; I hope that this will become evident in your life.” Pia blushed a bit and looked timidly at the crowd of students. She will never have known, but I have often used this event when trying to explain to children what is meant by pietism. Pietism is derived from pietas: piety. It also refers to reverence, an attitude that shows respectfulness.

Although pietism also protests against liberalism in doctrine, it stresses above all the need of a pious life. A pietist is opposed to superficiality and worldliness. It certainly is not the same as mysticism, but it can be influenced by it because of its desire to serve God from the heart.

“Pietist” has often been used as a term of abuse—of course by its enemies. For it has always given rise to opposition. The “moderates” within the church feel of course that they are being judged by the pietists’ pious way of life. And then the mockery awakens, the abuse is born.

In spite of all the pitfalls and imperfections that can be found in pietism, we have to conclude that the movement has brought many good things to the church. We want to look at this a bit more closely.

The English pietists (the so-called Puritans) were, especially at the beginning, very much focused on the church’s return to the purity of God’s Word. With the pietists in Germany there is a difference. German pietists were first of all concerned with personal piety. They come together in small groups, the so-called societies, in order to concentrate on prayer, pious discussions, and study of the Bible. They don’t leave the church, but form something like a church within the church. Little islands of piety.

This again is a typical characteristic of pietist movements: withdrawal to feed one’s own pious soul. It is true: the churches have in most cases asked for it. Believers are left without spiritual food, because in the church they receive stones for bread. And they are upset about the worldly lifestyle of many church members.

Another thing that one notices with pietists is that they are doers, Christians of action. They do much for the education of children, invest enormously in works of charity, publish much Christian literature and many spiritual hymns, and are busy with the work of spreading Bibles and with mission. The congregations of the Moravian Brethren (the Hernhutter) form the best-known pietist organization in Germany.

Pietism stresses feelings very much. The emphasis on faith experience becomes so strong that it becomes a distinguishing mark of true faith. Pietism has as characteristic: without a sudden, direct intervention of God in your life your faith is not real. Again you see a deep pitfall of the pietist movements. The personal struggle becomes the condition of your salvation.

Pietism has had much influence also in The Netherlands, and it continues to do so. You see it today in all sorts of publications, films, and testimonies. It is important that you recognize it and don’t allow it to take away your joy of faith. It is true, sometimes God powerfully intervenes in someone’s life in order to bring him back from a wrong path. But the Bible also has many examples of people who, without “spiritual crises,” have in true love served God all their life.

The Labadist: If Mummies Could Speak…←⤒🔗

Yes, in that case you would hear a story of Dutch mystical piety. It is worthwhile to visit the old church in Wieuwerd, a small village in Friesland. In the burial vault of that church are the famous mummies of the Labadists.

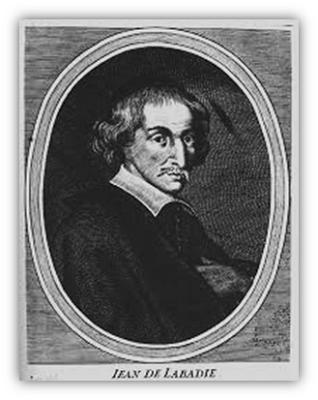

As the name suggests, we are speaking about the followers of Jean De Labadie. This man was invited to the Netherlands to support the so-called Further Reformation [a period in Dutch church history in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that had similarities with English Puritanism and was influenced by it]. But soon people regretted having called him in. Rev. De Labadie appeared to be a fanatic, a real Donatist. His efforts for a pure church and life have left us with bizarre memories.

What caused the conflict between De Labadie and people like Professor Voetius and other leaders of the Further Reformation? Firstly the fact that for him the group, the society of people with the same ideas, is far more important than the church. He rejects children’s baptism and sets up a church group where people live in community of property. The requirement for purity goes so far that the members are obliged constantly to confess all their sinful thoughts, words, and deeds to the entire congregation.

What is even more striking is Rev. De Labadie’s attitude toward the Bible. Always again you notice with movements that radicalize that the “inner light” becomes a source of divine revelation next to the Bible. Or even above the Bible. You get this also with movements like the Anabaptists and the Quakers. This “inner light” can have different names, but in essence it is everywhere the same. And De Labadie also differentiates between the “inner word” of the Spirit and the “outward word” of the Bible. Of himself De Labadie says that he possesses the “inner word” and that therefore he can form a pure congregation of born-again Christians.

Many rich and learned people join De Labadie. Among them are the famous Anna Maria Schuurman and three sisters from the Frisian Walta family. They follow him on his wanderings even as far as Germany and Denmark. When in 1674 De Labadie dies, the Labadists move to the Walta castle in Wieuwerd. There the sect finds rest, and there it dies. No new members are admitted any more. The money supply runs out and the community of property gets exhausted. The castle—“the Labadist monastery”—falls into decay and is demolished.

The memory of the movement remains in the burial vault of the church in Wiewerd: for generations the Walta family has been buried there and the Labadists also find their last place of rest in that vault. In 1765 people make a strange discovery. The corpses in the vault have not disintegrated but have been mummified. When that becomes known the vault is frequently desecrated. Intoxicated pub-visitors enter the vault at times to show their daring, and they take along one of the shrivelled parts of the bodies.

But a part of the mummies is still there. Those who visit the burial vault in Wiewerd stand face to face with the history of a pietist movement that flourished and then died. One also stands there with the question: Who was Anna Maria Schuurman, and what can we learn from the story of her life?

So much for this look at the past. Of course we have not been nearly complete. But it is sufficient for turning to the present. That we will do in the next article.

Add new comment