Being the Church in a Post-Christian Culture

Being the Church in a Post-Christian Culture

What is the position and meaning of the church in our culture? What is the effect of secularisation on faith and life? What was it like in the early church? What changed when the Roman Emperor Constantine elevated the church to become a state church? What can we learn from all this? That is what this article is about.

Secularisation⤒🔗

The churches in the West today find themselves in a crisis situation. It is a deep crisis that has everything to do with western society having gone through the process of secularisation. Religion has less meaning for society and individual people than it once did. Today it is a matter of specialization: all sorts of subsystems function within our society, each with their own specialism. The church too is one of these subsystems: it is the place to practise religion. People are less inclined to allow their daily lives to be influenced by religion. Connected to this, the process of secularisation continues: more and more people are turning away from the church. This is being caused, among other factors, by the strong increase of individualization: the individual person develops his own identity by making his own choices. In this he no longer lets himself be led or inspired by the community or society around him, even though he is a part of it. One of the most noticeable effects of the progressing individualization is that people – including within the churches – are aiming for ‘authentic personal experience’. It is one’s own ‘I’ that consciously seeks to achieve an ‘authentic expression of one’s own inner self.’ It is the person himself that makes decisions and makes choices concerning his own life, and thus also where his ‘religion’ is concerned. For man is truly emancipated!

This emancipation, however, evokes a crisis. Now that the ‘I’ is regarded as the true source of self-identity, insecurity and doubt simultaneously arise, because, while modern man had complete confidence in himself, post-modern man has completely lost that confidence. Post-modern man is searching for his self. What determines his identity? What does he have to hold on to? In short, the continuing effect of secularisation clearly results in the ‘marginalisation’ of faith and, connected with that, of the position and function of the church.

Back to the Beginning←⤒🔗

Through the process of marginalisation the church has been thrown back to considering the reason for her existence. Why is the church here? What is the message that keeps her alive and gives her the ‘right’ and even the calling to be present in this world?

The crisis in which the church finds itself summons her to revisit the sources from which she has always derived her existence. We are then referred directly back to the church as she was in the times before 313 when, in the edict of Milan, Emperor Constantine declared the Christian faith to be a privileged faith, ushering in the Constantine Era. From literature describing the early church, the image arises of the Christian congregation clearly occupying a minority position. The church was socially isolated and was being persecuted. Society did not grant the church a valued position within it. At the same time, it must be said that the church was not consciously seeking such a valued position. The church knew itself to be ‘not of this world’, which did not mean that the believers took up the position of ‘world avoiders’. Their ‘being different’ actually manifested itself in their open countenance towards the society in which the congregation lived. In this sense, the missionary attitude therefore became a natural part of the church’s existence. The church not only preached the message, she also lived it, and people around them noticed it. The disciples embodied the message that they brought.

A consequence of the persecution that took place was that it was a far-reaching step for ‘outsiders’ to join the Christian church. Such a step could cost you a great deal. That is why we can safely say that the church consisted of convinced Christians. At the same time, that strong conviction was a factor explaining the rapid growth of the young church in the first centuries. The clear message of the gospel, proclaimed with the conviction of, and reliance upon, eye and ear witnesses, was for many something to hold on to. The pure way of life in the Christian communities was also an obvious factor. Many lived sincere and noble lives amidst the fast deteriorating morals of those days, especially in the large cities of the Roman Empire with their sexual excesses and public barbarity. A final factor was the effect of persecution, which had just begun. Because Christians were often forced to gather in secret, many wild tales were circulating among the Roman population about these Christians. This brought on the cry to destroy these ‘terrible’ Christians. The attitude of the martyrs, however, made a deep impression upon onlookers, often causing the spectators of the gruesome events to start pondering their lives and converting. So one could say that the church in the first centuries was very alive, drawing life from the source and living from the power of the gospel.

Constantine←⤒🔗

All this changed when Constantine came to power and granted the church a privileged position. Persecution came to an end and the church was allowed to rest. The question is whether that change should be evaluated only positively. It is a well-known fact that John Wesley called the time after Constantine ‘a time wherein Satan gained a fatal advantage over the church of Christ.’

From the days of Constantine the church moved from the margin to the centre of society. In that society she now received a function that clearly placed her identity under pressure. Before Constantine liberated her from suppression, the church fully professed Jesus as Lord (kyrios). Now that Constantine had given her a privileged position, alongside came a second kyrios – the emperor. The emperor had a clear say in matters and he used that voice, sometimes very literally. The church lost its freedom in many aspects regarding society: it was expected to have a positive approach to the state institutions, not to criticize them. The contradiction between church and society faded and it became much easier for people to become a member of the church. In 529 it was even compulsory to become a Christian. This led, on the one hand, to a growth in the number of church members, but on the other hand, it formed a threat to spiritual life in the church, because many new church members became Christians in name only. The growth of the church brought the need for larger buildings for the church members to gather in. Church life therefore gradually moved from the small house gatherings, which was how it had been functioning during the first centuries, to a larger and more impersonal religious practice in a spacious church building. Normal members of the congregation were pushed more and more to the margins, while the main event was being carried out somewhere in the front of the church by the clergy. The church changed from a church of believers into a church for believers, and a distinction was being made between the clergy and the laymen. The ‘believers’ were becoming passive attendants of the liturgy, especially after 360 when even joint singing was no longer permitted. Another result was that the Christian testimony weakened. The church was not expected to criticize the affairs of the state. The message that was being passed down from the Bible was supposed to support the new context in which the church had received a legitimate position. That robbed various Biblical themes of their lucidity and radicalism, for example concerning what Jesus had said to his followers in the Sermon on the Mount. Large portions of New Testament teaching were classified as unobtainable idealism. It would all become reality in an eschatological Kingdom, but now it could not be done!

A final change to take place concerned the mission work. When Constantine granted the church a position in his Empire, the church originally gained new possibilities that gave missionary work an impulse. However, the initial growing missionary incentive gradually changed. The church concentrated less on missionary work and more on maintenance. That was connected to another change that was taking place. The church was becoming an institution rather than a movement. As a movement the church is progressive, as an institution it is conservative; as a movement it is active, influencing the environment, as an institution it is passive, adapting to influences from outside; as a movement it looks to the future, as an institution it looks to the past; as a movement the church is prepared to take risks, as an institution it is afraid to do so; as a movement it crosses boundaries, as an institution, by contrast, it guards boundaries.1

And Now...?←⤒🔗

Returning to the situation in which the church finds itself today, it becomes clear that the church has truly arrived in a deep crisis. What is the message that is keeping her alive and gives her the right and even the calling to be present in this world, especially when the world begrudges the church its position now that the era of Christianity is over?

Theology serves the church, so has a responsibility to search, constantly revisiting the foundations, for the manner in which the essential characteristics of the church, handed down to us from the Bible, can take shape today. Certain factors should be taken into account when doing this. Firstly, it should be clear that the situation in which the first congregations developed in New Testament times cannot be directly compared to our situation today. The time in which the church developed can be characterized as a pre-Christian era. We now live in a post-Christian era. There are certain similarities in the sense that many hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of the people today know nothing of the content of faith, just as they knew nothing in the pre-Christian times, but the differences are so substantial that they become a determining factor. Another distinction is that post-Christianity cannot be equated with post-modernism. While one cannot say by definition of post-modern man that he has and wants nothing to do with the church or with faith, it is true that post-modern man wants nothing to do with an absolute standard of truth, and this often does lead to the rejection of the absolute truth of the Bible. In this one could discover some connections with the process of secularisation, which stood at the transition to the post-modernist culture, but the effects of secularisation on these processes take place at different levels. It is for this reason that the questions put to the church today are on a different plane.

The crisis in which the church now finds itself is therefore of a completely different order from whatever crisis has been before. It is a case of a crisis on a cultural plane. In anthropological terms, post-modern man living in the post-Christian culture is a culturally very different person from his counterpart in previous centuries. At the same time, it is a case of an historical crisis, because the post-Christian culture has, throughout the process of secularisation, consciously left the period of the church behind it. It is also a case of a theological crisis because the church, through the developments going on around her (which do not leave her unaffected), discovers in various ways that something of a breach has developed between her existence now and her existence as it took shape in the beginning.

In Conclusion←⤒🔗

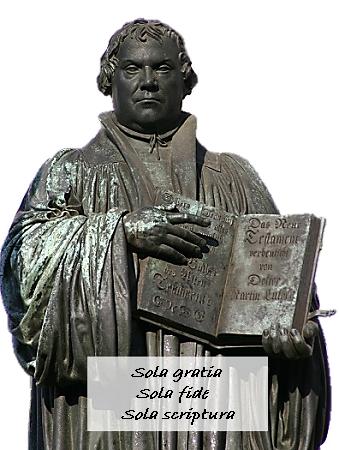

Yet this is not all there is to be said. The church must not walk away from the crisis but confront it, listening honestly to the questions that are being asked. The church need not fear that process of reconsideration. The crisis in which the church finds itself can grant the church the opportunity to become complete and truly the church once more. We may cherish that expectation, especially when the church and her theology acknowledge the wealth of the tradition in which she stands and in which she can also be church today. That wealth has been expressed by the churches of the Reformation in the principles of sola gratia, sola fide and sola scriptura (by grace alone, by faith alone and by the Scriptures alone).

The three solas show that the church – upon reflection – does not belong to us. Firstly, she belongs to God. She originates from and lives out of his grace. Secondly, we may look upon her with eyes of faith, so that we can see that God is at work with his church, and that he is taking her with him to his future. Thirdly, the church lives from the only source that has been given to her: the Word of God. In it the church discovers the secret of her existence: God’s love and mercy. Therein the church also finds the patterns with which she can search for a way of being church today, in obedience to her Lord and Saviour. And that in such a way that she can explain to people of today that they too, post-modern as they are in a post-Christian culture, are being sought by the Lord and Saviour of the church. What these patterns look like, and what consequences they may and will (and maybe should) have for the church and for her functioning today – these are the questions that have a right to be asked. How should the church today explain to post-modern man that the Lord and Saviour of the church is seeking him or her? How should the church handle the distinction between clergy and laymen? What does it mean when the Bible speaks of the priesthood of all believers? Must the church look for new forms of community to make it clear that the church is a fellowship of believers in Christ, in which each believer represents part of the body of Christ and takes up their position therein with the talents given them? All these questions the church must confront honestly, prepared to listen to what the Bible presents to us, searching for ways and possibilities to apply what the Bible says. The church has this calling because she – although not of this world has been placed in this world, with Jesus’ word of promise: you will be my witnesses (Acts 1:8).

The church has been pushed to the margin. She has been deprived of the central position that she had acquired for many ages, but through this she found herself in a situation in which she can truly be herself. The church can have her say, because she does not speak her own words but the word of her Lord and Saviour. That word may, and must, resound: open-minded, inviting, encouraging, correcting, confronting, appealing to all people to believe and repent, to entrust themselves to Jesus Christ. That is the message with which the church stands in the world. The church has landed in a crisis. The crisis brings us – in a way – back to the beginning. There the Spirit was working in the rapid growth of the Christian faith in the first centuries. The situation in which we find ourselves as churches today, impels us – perhaps more than ever before – to expect help from the Holy Spirit in order to be the church of Christ in this world, as strangers and pilgrims, but always being prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks us to give the reason for the hope that we have (1 Peter 3:15).

Add new comment