God’s Eye Knows No Pity

God’s Eye Knows No Pity

The Bible: A Violent Book? (1)⤒🔗

If ever there was a prophet who proclaimed God’s love, it would be the prophet Hosea. His married life spoke volumes, both in his words and in his actions. He lived in a time filled with threats and violence. In the second half of the 8th century before Christ, the shadows cast by the aggressive superpower Assyria began to fall over the ancient Near East. Hosea’s prophetic eyes look behind the scenes of political and military violence and perceive God’s judgments in these events. It is the Lord who awakens the powers of death and hell to punish his people Israel: “O Death, where are your plagues? O Sheol, where is your sting? Compassion is hidden from my eyes” (Hos. 13:14). God’s eye knows no pity…

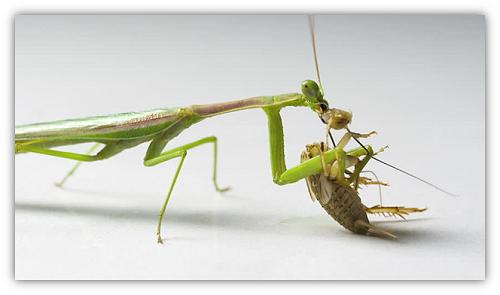

The covenant curses glow brightly in the horrific lot that befalls God’s people. When the storm of the Assyrian destruction finally abates, Israel is decimated, the capital Samaria devastated, and the people are in exile. It all started off so well in the book of Hosea, with messages about God’s alluring love in the desert and his speaking to the heart of Israel (2:14). The Valley of Achor would be a door of hope—beautiful! But soon thereafter God’s witness could be heard that he was like a lion to Ephraim, tearing and carrying off with no one to rescue (5:14ff.). The images pile themselves up: “So I am to them like a lion; like a leopard I will lurk beside the way. I will fall on them like a bear robbed of her cubs; I will tear open their breast, and there I will devour them like a lion” (13:7–8). It all started off with love, that’s true, but the book of prophecy is coloured dark red from blood and violence.

Staggering Numbers←⤒🔗

In this regard Hosea’s prophecy is no exception in the Bible. We all know that aggression and violence take up a remarkably prominent place in the Bible, specifically as found in the Old Testament. Enough reason therefore to pay special attention to this in three articles in De Wekker. Someone has calculated that the Old Testament contains 600 texts about murder, 100 texts in which God commands to kill, and 1,000 passages that speak of God’s anger, punishment, and war. It is not an exaggeration to typify the Bible as one of the bloodiest books of world literature, from the beginning (Abel’s blood crying out to heaven, Gen. 4:10) via the central part (“bloodshed follows bloodshed,” Hos. 4:2), to the end (a prayer for God to avenge the blood of those who were slain, Rev. 6:9). It should not be surprising that the word “hamas” that everyone has heard of by now (the Hebrew word for “violence”!) is frequently found in the Old Testament.

What do we need to do about a Bible that abounds with stories of violence? Can this book be our source and benchmark for faith and ethics? Ever since Verdun and the Somme, Stalingrad and Dresden, we modern people have been sensitized when it comes to violence, and we have developed a deep aversion to it. At the same time we witness in our time an explosion of religiously motivated violence. We’re quite at a loss when we get asked questions about revenge prayers in the Psalms, of executions and calls for hate in the Bible, and whether there actually is a difference between the Koran and the Old Testament on this point. Wouldn’t it free us from a whole load of problems if the theme of violence was not or barely mentioned in the Old Testament?

In the meantime our difficulty with this “dark side” of the Bible appears to mesh well with our modern way of thinking, our modern way of life. Violent traits in the biblical image about God, war stories, aspects of blood-abundant sacrifice or crucifixion, the perspective of judgment and eternal punishment—all of this doesn’t quite fit in our modern way of thinking. Periodical surveys about the religious experience of the average Dutch citizen show that we would rather wish for a mild God, one who is more “soft,” where we’ll have a good feeling at least. It is in fact remarkable that earlier generations of Christians and theologians were less significantly impacted by these problems of violence in the Bible.

A Counter-Intuitive Question←⤒🔗

I realize this may go against the grain, but should we approach the question also from another side? In some sense, may we not just be happy that the Bible also speaks of violence? Imagine for a moment that we had to work with a Bible where this theme was largely ignored. For there is enough evidence that violence is a structured element of our existence; no scientist will deny this. The fact that the Old Testament makes mention of it, in all sorts of scenarios, shows us the extent of how much this book elaborates on the realities of life. Who would be served with a Bible full of all sorts of wisdom and of pious reflections on salvation that are far removed from our everyday existence? Life is multi-coloured, raw, and at times mind-boggling. It is exactly the Old Testament that proclaims to us the reality of a God who in a real sense wants to interact with us, people. So when the Old Testament speaks extensively about violence, let’s have our ears tuned in. It is exactly in this present everyday reality that God’s Word wants to lead us, that it teaches us by way of discovery, and aims to provide us with directions.

Having said all this, we yet return to the concrete experience that many Bible texts, not in the least those of the Old Testament, confront us with difficult and challenging questions. Take, for instance, the stories of the scandalous act at Gibeah (Judg. 19), or of the dowry that David hands to King Saul (1 Sam. 18:27): downright shocking! May we not expect quite a different sort of language in the Bible, which is the church’s Holy Scripture, source of comfort and life? Three religions appeal to the Old Testament: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. None of these three “Abrahamic” religions knows a history that can be classified as immaculate as far as aggression and violence are concerned; quite the contrary. It is for that reason that often an accusing finger is pointed in the direction of the Old Testament: is that book not the source of so much misery? Is the Old Testament the origin of an endless history of violence?

I am reminded of a recent debate on monotheism in Germany. An Egyptologist from Heidelberg, Jan Assmann, postulated with much persuasiveness his thesis that the holy writings of monotheistic religions needed urgent revision so as to remove all references to any violence. He aims to apply it especially in the monotheism of the Old Testament, which with its exclusive claim to truth characterizes itself through the language of violence: God is shown to be “jealous,” he forces people to repentance, and demands total dedication (read: “zealotism,” or “jihad”). This God inspires punishment, and shuts out anyone who trespasses his command. The world of the ancient Near East was familiar with despots, with autocrats who ruled the masses through the system of power and violence. According to Assmann, this type of thinking is projected onto the God of the Old Testament.

Violence – In Every Tone←⤒🔗

It would put us on a dead-end road if at this point, where we are dealing with the theme of violence, we would simply seek cover in a shell of denial or of glossing it over. It is true, the Old Testament speaks on multiple levels of aggression and violence; no area of life has been excluded. Through the following cross section we show an image of it with the use of some clear examples:

Violence in Marriage and Family←↰⤒🔗

Immediately at the beginning of the Bible the mechanism of violence is shown to live at the core of human existence: the husband shall “rule” over his wife (Gen. 3:16), and the one brother, blinded by jealousy, kills the other (Gen. 4). All in all, a prelude of what is to follow in world history.

Violence between Individuals←↰⤒🔗

Sexual abuse and violence, followed by murder, are paramount in Gibeah (Judg. 19) and among David’s children (2 Sam. 13). David himself added murder to adultery (2 Sam. 11).

Violence in Society←↰⤒🔗

Where the authorities allowed justice and righteousness to part ways (Ps. 94:15) the widow, sojourner, and orphan become the victims (Ps. 94:6). Naboth learned this as well (1 Kings 21).

Violence between Nations←↰⤒🔗

A way is paved for Israel from the land of slavery to the land of milk and honey. In the meantime, Egypt’s army is annihilated, Amalek meets a devastating defeat, the Amorites under Sihon and Og lick the dust, and the ban is pronounced over Jericho. Israel receives the order to annihilate the Canaanite peoples (Deut. 7).

Violence toward Animals←↰⤒🔗

A river of blood flows from Israel’s altars—just on the occasion of taking office alone, Solomon sacrifices a thousand burnt offerings (1 Kings 3:4).

Violence through Nature←↰⤒🔗

In the flood, the world population is eradicated, except for a handful (Gen. 6-9).

Religious Violence←↰⤒🔗

Phinehas’ zeal for God marks the conclusion of a massacre among the unfaithful Israelites; in one day 24,000 people are killed (Num. 25:9). The failing priests of Baal are killed on Carmel, to the last man (1 Kings 18), and Samuel cuts Agag to pieces (1 Sam. 15:33).

Divine Violence←↰⤒🔗

God asks of Moses to let his wrath burn hot and to consume his own people Israel (Ex. 32:10). He strikes down seventy men of Beth-shemesh who had looked upon the ark (1 Sam. 6:19). The Lord descends from Edom in crimsoned garments, spattered and stained with the lifeblood of the people he trampled (Isa. 63:1– 6). A central biblical motif is that of God as warlord.

Add new comment