God’s Almighty Power

God’s Almighty Power

Part I⤒🔗

A Power of Error←↰⤒🔗

When in the 1950s, and especially also in the ‘60s, a crisis of faith revealed itself in the lives of many, one may not have suspected how serious the consequences would be. People loudly proclaimed that they wished to hold on to the essence of faith, and assured us that they loved the Reformed confessions. Yet they wanted to be able to breathe more freely.

Should we believe the Bible exactly as it was given to us? And should we keep to everything that God commanded in his law? Should people not be listening more to the people of science, and take their discoveries and expertise into account? And should we, as modern people, still believe that there is one God, who from eternity decreed our eternal weal and woe? And really, are we actually guilty on account of the trespass of the first man (if a certain Adam had even lived in Paradise?) People were of the opinion that one could think differently about these things, and they were disturbed if someone pointed to a binding to our confession, which clearly stated these matters. In the meantime many sincerely thought that with freer attitudes the most important things would continue to be upheld, namely, the facts of salvation and the deity of Christ.

Should we believe the Bible exactly as it was given to us? And should we keep to everything that God commanded in his law? Should people not be listening more to the people of science, and take their discoveries and expertise into account? And should we, as modern people, still believe that there is one God, who from eternity decreed our eternal weal and woe? And really, are we actually guilty on account of the trespass of the first man (if a certain Adam had even lived in Paradise?) People were of the opinion that one could think differently about these things, and they were disturbed if someone pointed to a binding to our confession, which clearly stated these matters. In the meantime many sincerely thought that with freer attitudes the most important things would continue to be upheld, namely, the facts of salvation and the deity of Christ.

But the error has an inner dynamic. It is like a cancer that you cannot localize, but it continues to eat away, as Paul says in a picturesque way (2 Tim. 2:17). At some point the switch is made. People begin to criticize God’s Word. The first to do so may still retain a certain trepidation and respect, but their followers go much further. And the practice shows how it proceeds from there. Nothing is then safe for the coming avalanche. After questioning some of the miracles of the prophets and of Jesus himself, soon questions arose about the virgin birth, about ascension, and about the resurrection of Christ himself. And also the atonement of sins through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was denied, especially since the beginning of the 1970s, also in Reformed circles.

It is no wonder that this also had consequences for the thinking about God himself. Under the influence of Bonhoeffer, and especially also of J. Moltmann and D. Sölle, people no longer wanted to hear about an almighty God, as we confess this in the Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Days 9 and 10. No longer could we be singing:

“Who limits his dominion ever?

He rules creation from on high;

all that his love and grace endeavour

shall him his power not deny.”

A person who of late has exercised a lot of influence is Harold S. Kushner, even though he brings a somewhat unique message in this regard. In his well-known book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, he judges that God does not cause tragedies, but that he cannot prevent them either. This is clearly in contradiction with the classical confession of God’s omnipotence.

That such reflections affect groups of people who want to be called professing Christians can be compared to the proverbial writing on the wall. It is certainly connected with the delusion that we as humans, even as Christians, are “emancipated,” and that it would be undignified that our life and destiny be decided and guided by an almighty God. Hence the often-heard criticism of Lord’s Days 9 and 10 of the Heidelberg Catechism.

Questions about God’s Omnipotence←↰⤒🔗

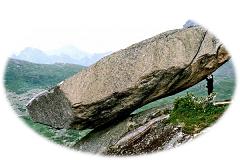

Throughout the ages, all kinds of questions have been raised about the doctrine of God’s omnipotence. Can God, if he is almighty, really do everything? But God cannot sin. Neither can he deny himself. But also, can God undo the past?  The medieval scholastics raised the question of whether God in his omnipotence could create a stone that he himself would not be able to lift. The nominalists argued that God had indeed become a man according to his ordained power, but that, by his absolute power, he could also have accepted the nature of a donkey or a stone. All of this has rightly provoked sharp criticism, and all such foolish reflections may well have given theology a bad name. And that is understandable. However, abuse should not stop the good use of something. And there are also genuine questions in this regard. Modern liberal theology, which we reject wholeheartedly, does confront us with this matter. There is untold grief in the world, and this is not always the result of personal sins. And God faces this in apparent powerlessness. It has also been the fearful question of prophets and psalmists (Isa. 63:11ff.; Pss. 22, 73, etc.). But these found peace in God. The modern prophets become rebellious, or start to excuse God, by saying that God is also powerless and that he is sympathetic to the oppressed, or they claim that God is struggling along in man’s development. However, we must examine the opinions of Sölle, van Reve, Kushner, Van de Beek and whoever they are, in the light of God’s Word. Then the question can also be raised whether everything had to go the way it did, and whether God could not have changed the course of history any differently. And that is why we first want to listen to what the OT and NT teach us in this regard.

The medieval scholastics raised the question of whether God in his omnipotence could create a stone that he himself would not be able to lift. The nominalists argued that God had indeed become a man according to his ordained power, but that, by his absolute power, he could also have accepted the nature of a donkey or a stone. All of this has rightly provoked sharp criticism, and all such foolish reflections may well have given theology a bad name. And that is understandable. However, abuse should not stop the good use of something. And there are also genuine questions in this regard. Modern liberal theology, which we reject wholeheartedly, does confront us with this matter. There is untold grief in the world, and this is not always the result of personal sins. And God faces this in apparent powerlessness. It has also been the fearful question of prophets and psalmists (Isa. 63:11ff.; Pss. 22, 73, etc.). But these found peace in God. The modern prophets become rebellious, or start to excuse God, by saying that God is also powerless and that he is sympathetic to the oppressed, or they claim that God is struggling along in man’s development. However, we must examine the opinions of Sölle, van Reve, Kushner, Van de Beek and whoever they are, in the light of God’s Word. Then the question can also be raised whether everything had to go the way it did, and whether God could not have changed the course of history any differently. And that is why we first want to listen to what the OT and NT teach us in this regard.

Biblical Data←↰⤒🔗

Many people before us have already consulted the Bible about this topic. The question can be asked why we have to raise those questions over and over again. But every time again we are confronted with so much contention against our confession that we are compelled, each time with renewed energy, to point to the same Word of God, which is alive and powerful. The OT speaks often about God’s omnipotence or about the Almighty. We then read of El Shaddai or just Shaddai. And in the NT we read, especially in Revelation, about Christ as pantokratōr. This means, literally translated, someone who has power or strength to do all things.

In this sense we also read of God’s omnipotence, especially with the patriarchs Abraham and Jacob. The LORD fulfills his promises. He will make Abraham into a great nation, yes, into a father of many nations. God will make him inherit Canaan. God can also give a son from Sarah’s “dead” womb, the son of the promise. With this son God will establish his covenant, though Ishmael also belongs to the covenant, and he too receives circumcision (Gen. 17:20, 21, 23). In the beginning of this chapter, God introduces himself as the Almighty One, who fulfills his words and promises, who can do it, even if it seems so impossible. This is the same with Jacob (see, e.g., Gen. 48:3; 49:24, 25), and with the prophets and, e.g., in Psalm 68. The Almighty will fulfill his promises. The LORD is not omnipotent in the sense that he would do miracles for unbelieving, curious, or sensuous people. When Herod sent for Jesus to be entertained by him, and Herod wanted to see a sign from Jesus, the Lord disappointed. How else could it be? For Herod, Jesus was the talented wizard who would surprise him in some of his arts. What a deep humiliation the Saviour receives here! Classified earlier among the murderers, he is here among the magicians. Obviously Jesus cannot show his omnipotence in such a situation. We can through our small belief or disbelief prevent the Lord from showing his power, such as it happened in Jesus’ own city (Matt. 13:58).

Also in the NT God’s omnipotence becomes clear, especially, as mentioned, in the book of Revelation. There God shows himself as the Almighty, who rules over all nations, who also sends judgments on earth, but who leads his people to complete salvation. The LORD shows himself as the Sovereign, who leads history through the ages. His Son, who sits enthroned at God’s right hand, performs all of this. In this way the church is kept throughout the ages, in battles and victories. This continues until the time that the children of God are in the city where there is no more temple, because the Lord God, the Almighty, is its temple, and the Lamb. The Almighty then has thus preserved the church that the gates of the realm of Hades (death) have not overwhelmed it. The terrible powers of Satan and the world could not compete with the saving omnipotence of God. In the beginning of the book of Revelation (Rev. 1:8), the Lord, who is the Alpha and the Omega, and who bought the church with his blood, presents himself as the Almighty. It is not an earthly force that leads history to its goal, and that delivers us from all dominion of the devil. In Rev 4:8 he is portrayed as the high majesty of the Lord. He is enthroned far above the tumult of the nations. What do all those great and terrible powers mean to him? God is worshiped as the Almighty, he created everything, only by wanting it and speaking his Word. Is there then an earthly, created power that can be compared to him?

In chapter 11 the enemies of God appear to have conquered. The dead bodies of the two witnesses lie in the streets of the city that is spiritually called Sodom and Egypt. But then God shows his omnipotence. The two witnesses arise, as Christ arose on the third day. And who will then survive when God makes himself known in the Day of Judgment and retribution as the Almighty (Rev. 11:9ff.)?

In chapter 11 the enemies of God appear to have conquered. The dead bodies of the two witnesses lie in the streets of the city that is spiritually called Sodom and Egypt. But then God shows his omnipotence. The two witnesses arise, as Christ arose on the third day. And who will then survive when God makes himself known in the Day of Judgment and retribution as the Almighty (Rev. 11:9ff.)?

Also the victors at the sea of glass (Rev. 15:1ff.) praise God as the Almighty. At one time the people had been delivered from the slavery of Pharaoh by God’s great power, and they sang their victory song by the Red Sea (Ex. 15). Now the believers from the old and the new covenant are singing to the praise of the LORD, who has saved them from certain death by the blood of the Lamb. And they praise the Lord as the Almighty who rules over everything. Also in Revelation 16:7 the omnipotence of God appears again in the judgment of all the enemies of his people.

Preliminary Conclusions←↰⤒🔗

Our preliminary impression is that in any case, God’s omnipotence must never be spoken of in a theoretical or abstractive manner. It is not a matter for a conference of some philosophers, or of theologians, who do not want to bow to God’s Word. Only by showing deep respect for what God himself says about his omnipotence are we able to proceed further.

The omnipotence of God is noted in our confession, our praise and worship. This is solidly based on God’s revelation, which shows God’s omnipotence in the history of people. The modern thinker makes it appear as if we ourselves thought of a God who was so powerful, and therefore described him in such a way and then praised and adored him. But then we worship based our own ideas and thoughts. God is the living God, for whom nothing is too wonderful. He remembers his grace, and for that reason he is worshiped and adored.

Furthermore, a first exploration in the Scriptures points out that God’s omnipotence is always mentioned in connection with salvation, with his counsel, which we worship and by which he wants to save his people. Thus in Lord’s Day 10 of the Catechism, providence is called the almighty and ever-present power of God. And this is also associated with creation. God calls things that are not as if they were. That is an incomparable power. Only in a derivative sense can we speak of our (created) power. But the uncreated and eternal power of God serves such that God preserves us, that no creature will separate us from his love. That is how God can direct things in his counsel in times of sickness, of hunger and persecution. But in all of this we may remain more than conquerors because of God’s omnipotence.

In the meantime, as we have seen, it is clear that God cannot be challenged to do all kinds of miracles according to our will and fancy. Satan says to Christ on the pinnacle of the temple: “Throw yourself down for it is written in the psalm, ‘He will command his angels concerning you’” And can the Lord not do that? Yes, but the Lord cannot and does not want to reward indifference and tempt God by performing a miracle.

On the other hand, when the Lord invites us to ask of him and to make an appeal to his omnipotence, then we may freely go to God. Ahaz was allowed to ask a sign from the Lord, either from the depths or from the heavens above. However, with an appearance of piety Ahaz said that he would not do that and would not put the Lord to the test (Isa. 7:10-12). In fact, however, it was wickedness of Ahaz. He did not need God and his Word and would attempt to save himself, without the miraculous intervention of God. Here Ahaz is really a type of modern man who lives in a “deified” world, where we have “demythologized” the Bible. We have to help ourselves, then God helps us.

Prayers in town council chambers are a thing of the past. And praying for God’s blessing in the beginning of a new parliamentary year cannot really be tolerated and it annoys many people. In considerations about political and social affairs, people hardly hear about the help and the power of God Almighty, even with people who want to maintain that they are Christians.

How did everything end up like this? And what should we think in regard to God’s omnipotence and his apparent powerlessness, of God’s almighty power and our responsibilities? More on these matters in the next two articles.

Part II←⤒🔗

How is it that the confession of God’s omnipotence devalues so much in our present time? We noted in the previous article that there is a power of error that has its effect. If one or more bricks start to become loose in the building, in the “house of doctrine,” soon the whole building will collapse. But we have also seen that the omnipotence of God comes true in the works of creation and recreation. The Almighty calls the world – out of nothing – into existence.

And it is he who brings the dead to life, also those who are spiritually dead. And it is precisely this confession of creation and re-creation that is being attacked. But then irrevocably the confession of God’s omnipotence is also affected. Evolutionary thought has rapidly gained ground. We think of people such as Teilhard de Chardin in Roman Catholic circles, or of J. Lever along with those who still like to be seen as Reformed. The creative power of God is pushed far into the background. At most, the Lord guides the evolution process. But God’s mighty intervention is being pushed aside.

And in re-creation, the renewal of man and the world, a very great role is attributed to man himself. It is true that people no longer think as optimistically about man and the world as in the time of the Enlightenment of the 18th and the 19th century. But we still have to do the job. There is a beckoning perspective of a world, where justice will reign, where there should be no (nuclear) weapons and no more oppression. People follow a somewhat Christianly-tinted humanism. They no longer live by what the Scriptures teach, that man is dead in himself in sins and transgressions, that we cannot arrive without the divine work of renewal through the Spirit. Rebirth, renewal are not things that we bring about, but they are a work of God’s Spirit, just as glorious as the creation or the resurrection from the dead (Canons of Dordt III/IV, 12). However, one does not hear about that almighty power of God. In liberation theology, the influence of Karl Marx is often stronger than that of Christ. Also the whole aspect of eternity is threatening to disappear beyond the horizon of materialistic thinking. In this way people are losing the confession of Christ’s death, his bodily resurrection, ascension, his sitting at God’s right hand, and his return. Only the company of the poor is left. The apostate thinking about creation and re-creation is connected. Just as people teach evolution in creation, so also in redemption. Man has to improve continually. The ultimate sin is to hold back this progressive thinking. Through all this spiritual degeneration the glorious introduction of the Apostles’ Creed, “I believe in God the Father, the Almighty,” is completely deprived of power.

A Bit of History←↰⤒🔗

Much thought has been given to the omnipotence of God in the course of the centuries. H. Bavinck, in his Reformed Dogmatics, mentions the aforementioned standpoint of the nominalists, who argued that God could not only do everything he wants (we also confess that), but that God can also want everything. In this way God could also sin according to his absolute power, but there is an ordained power by which God cannot and will not sin. Calvin expressed sharp criticism against such a distinction. For example, Calvin took a strong position against the Roman defense of transubstantiation. According to them, if God is almighty, then he could also ensure that the same flesh (the body of Christ) is present in many places at the same time. Calvin then rails out and says that when God chooses, he can change light into darkness and darkness into light, but one can never say that light and darkness are ever one and the same thing, because then we distort the ordinances of God. And so it is God’s ordinance for the flesh that it is bound to one place (Institutes, IV, 17,24).

On the other side, argues Bavinck, stood those who limited God’s power to what he is doing and has done. Whatever does not become reality is not possible either. That implies that God has exhausted his power in the world. Bavinck proceeds to give a list of supporters of this view, which does not inspire much confidence. Abelard’s name is prominent, along with Spinoza, Schleiermacher, the more modern D. F. Strausz and A. Schweizer. Both notions are rejected by Bavinck. We have already written about the “absolute power” of God. But the other conception is not tenable either. Can we limit God’s omnipotence to what is in fact happening? Bavinck points to the texts that state that all things are possible with God. He also mentions the words of John the Baptist that God was able to raise children of Abraham out of stones. But did God do that? We could continue to philosophize.

Reality and God’s Potential←↰⤒🔗

From the discussion between God and Abraham about Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 18:22ff.) it appears that the Lord would not have destroyed these cities if only fifty, or even ten righteous people were found within their walls. How different history would have been. The conversation, the fervent intercession of Abraham for these cities was not an idle display. There was a real possibility that the cities would be saved. Certainly, on the other hand, we believe the eternal and unchanging counsel of God, in which the fate of these cities was established (see also 2 Peter 2:6). But not only what became reality is possible with the almighty God. King Joash visits Elisha when he lies on his sickbed, which also became Elisha’s deathbed.  The prophet orders the king to shoot from the opened window to the east. This was the direction toward the hostile nation of Aram (Syria). However, when Joash had hit the ground three times, Elisha said, “You should have struck the ground five or six times; then you would have struck down Aram decisively.”

The prophet orders the king to shoot from the opened window to the east. This was the direction toward the hostile nation of Aram (Syria). However, when Joash had hit the ground three times, Elisha said, “You should have struck the ground five or six times; then you would have struck down Aram decisively.”

Again, how different the history could have been if the king had been more determined. In his omnipotence, God could have also brought about this definite victory (see 2 Kings 13:14ff). In 2 Sam. 24:12 the prophet Gad, on behalf of the Lord, presents David with three possibilities as punishment for sin. In the end, David chose that he would rather fall into the hand of the Lord than into the hands of men. And so a terrible plague, an epidemic, occured. But there were also two other serious options: a famine of seven years or three months of being pursued by the enemy. And it appears from the prophecy of Jonah that if the city of Nineveh had not repented it would indeed have received a terrible judgment in those days. All this is not a fabrication of speculating theology, but it is according to what the Scriptures tell us. In Psalm 81 we read the other way around, that the judgment on Israel came about because the people did not want to listen to God’s voice. Otherwise the Almighty would have led history very differently, if Israel would have walked in God’s ways (v. 13). When Jesus is taken prisoner, he expressly says that he could have prayed the Father, and more than twelve legions of angels would stand by Jesus (Matt. 26:53). God is capable of more than what is actually happening, even though it is also clear that it could not have happened any differently. After all, Jesus had to die for the sins of the world. Therefore, the almighty God “could not” and did not want to deliver his Son at that time. God’s omnipotence would only come out wonderfully on Easter morning, when the guilt had been paid for and death had been conquered.

In our speaking about God’s almighty power we must remain within the bounds of Scripture, and God’s omnipotence comes out in the fact that his counsel of salvation will endure and he will accomplish everything in his good pleasure. Then we should never think too small of God’s omnipotence. Abraham was not allowed to do so when the Lord promised a son to Sarah and him in their old age. Mary also was not allowed to think too small of God’s power when she was told that she would become the mother of the Saviour. Neither may we think too small of God’s omnipotence; we may expect from him everything we need for our eternal salvation.

God’s Almighty Power and Predestination←↰⤒🔗

God has in his eternal counsel determined everything. Whether I am saved or lost, that is forever certain with God. We cannot take away from this confession. At the same time we may never be caught in an anxious crisis of fatalistic thought. We can always appeal to God’s omnipotence; he can and will save us from eternal death. Thus Bavinck writes that no one should believe that he is a reprobate, “for each one is called earnestly and urgently, and is obliged to believe in Christ for salvation.” Bavinck goes on to say that people cannot believe that they are reprobate and do not actually believe it, because then hell would already be on earth. And W.H. Gispen warns us that God in our thinking degenerates into a necessity. He cannot love that necessity, especially if it is necessary for me to be eternally doomed. “My only comfort would then be that I defy the necessity and bravely endure my condemnation, without ever committing the inconsequential call of ‘Grant grace, O God!’ That is how one could draw inferences from the system of predestination. And according to the other system, God simply has to wait and see what I will do; and if I can do something other than what God actually wants, then he is not God” (Gispen, 1877).

Instead we confess that God knows his people from eternity and that no power is so terrible, or God saves us in his omnipotence. We also know that people who are sincerely seeking and praying may hope and count on God’s good pleasure. We believe that this reflects most profoundly the meaning of what Bavinck and Gispen have written. However, those who mock God’s omnipotence and persevere in this will one day experience it in a terrible way.

God’s Omnipotence and the Power of Sin←↰⤒🔗

It is understandable that our belief in the almighty power of God is being contradicted. This is not strange in itself. Christ himself is a sign that is contradicted (Luke 2:34) and the leaders of the Jewish community in Rome said that the gospel that was proclaimed found opposition everywhere (Acts 28:22). It would also be a bad sign if the world only showed us appreciation.

However, as we have seen, the confession of God’s omnipotence raises questions, also for us. Why doesn’t God save all people? After all, is he not also powerful to renew the heart of the most hardened sinner? Why does God leave so many – even if it is according to his blameless and righteous judgment – in their ruin? Why do we see such terrible misery in the world, the suffering in the concentration camps, not just in the era of Hitler but also now? We hear little of the suffering of Christians in Marxist countries and in empires under Islamic rule. Why does God allow it? One nod from him, and the enemy is powerless. Why the incurable sick, and how can the almighty God allow a precious child to be killed by a drunken driver? Unbelievers and scoffers like Van Reve are quick with their verdicts. They have only ridicule for this belief. And in fact, many modern “Christians” claim they are right. May the Lord protect us from going along with their ridicule and scorn. Yet we also have and continue to have our questions. We pointed to the peace that the psalmists and prophets eventually found in the providence of God. We can also listen to Calvin, who says that we must be restrained by the Word of God, in regard to his incomprehensible counsel, which even angels adore (Institutes, III.23.1). And does not Paul say that it is improper for the creature to contradict his Creator (Rom. 9:20ff.)?

However, as we have seen, the confession of God’s omnipotence raises questions, also for us. Why doesn’t God save all people? After all, is he not also powerful to renew the heart of the most hardened sinner? Why does God leave so many – even if it is according to his blameless and righteous judgment – in their ruin? Why do we see such terrible misery in the world, the suffering in the concentration camps, not just in the era of Hitler but also now? We hear little of the suffering of Christians in Marxist countries and in empires under Islamic rule. Why does God allow it? One nod from him, and the enemy is powerless. Why the incurable sick, and how can the almighty God allow a precious child to be killed by a drunken driver? Unbelievers and scoffers like Van Reve are quick with their verdicts. They have only ridicule for this belief. And in fact, many modern “Christians” claim they are right. May the Lord protect us from going along with their ridicule and scorn. Yet we also have and continue to have our questions. We pointed to the peace that the psalmists and prophets eventually found in the providence of God. We can also listen to Calvin, who says that we must be restrained by the Word of God, in regard to his incomprehensible counsel, which even angels adore (Institutes, III.23.1). And does not Paul say that it is improper for the creature to contradict his Creator (Rom. 9:20ff.)?

However, Scripture does teach us that particularly in profound and difficult situations God does show his great power unto salvation. More about that in our final article.

Part III←⤒🔗

Omnipotence and Humility←↰⤒🔗

God’s power reveals itself in weakness. It is not through outward violence, not with soldiers and display of power, that Christ has delivered us from the tyranny of sin and death, but by humbling himself very deeply, to death, yes, to death on the cross (cf. Zech. 4:6; John 18:36; 1 Cor. 1:18ff; 2 Cor. 12:9-10; Phil. 2:5-11).

When thinking about this we are also confronted with many questions. Is God’s Son able to humble himself and let himself be reproached? Did God’s Son suffer, and did God himself also suffer? Can God, who is infinite and without measure, limit himself and did the Almighty impose restrictions on himself in the creation of the world and in the incarnation of the Word? We are obviously not the first to reflect about these things. There is a stream of literature about these matters. But the opinion of scholars is quite varied, which is understandable because it is about the most difficult things.

In the 19th century, especially in Germany, there was quite the struggle between the “kenotics” and the “cryptics,” i.e., between those who thought that Christ in his incarnation had let go of his divine attributes entirely or in part, and those who assumed that Christ did not discard these qualities but did not use them, at least not in public, only in the hidden. Of course the interpretation of Philippians 2:7 is of great importance here, where it says that he, who was in the form of God, emptied himself. We cannot go any further into this discussion now.

Was the Incarnation Itself Humiliation?←↰⤒🔗

It is well known that people within Reformed circles are not entirely in agreement on the question of the humiliation of our Saviour. As may be known, A. Kuyper defended the view that the incarnation in itself was already a humiliation for our Saviour. Helenius de Cock, a lecturer at the Theological School in Kampen, had a different view. His argument was strongly that if Christ’s assumption of human nature itself could already be humiliation, the Lord Jesus would still be humbled, for after all the Saviour’s human nature has never been deposed of, even though he has now an exalted human nature. Later, S. Greijdanus also dealt with this issue in a profound way. His point of view corresponded chiefly with that of De Cock. K. Schilder also wrote about it in 1940 in “The Feast of Joy According to the Scriptures.” In two substantial articles in this journal, T.S. Huttenga has recently presented a good overview of the discussions that have taken place.

It is well known that people within Reformed circles are not entirely in agreement on the question of the humiliation of our Saviour. As may be known, A. Kuyper defended the view that the incarnation in itself was already a humiliation for our Saviour. Helenius de Cock, a lecturer at the Theological School in Kampen, had a different view. His argument was strongly that if Christ’s assumption of human nature itself could already be humiliation, the Lord Jesus would still be humbled, for after all the Saviour’s human nature has never been deposed of, even though he has now an exalted human nature. Later, S. Greijdanus also dealt with this issue in a profound way. His point of view corresponded chiefly with that of De Cock. K. Schilder also wrote about it in 1940 in “The Feast of Joy According to the Scriptures.” In two substantial articles in this journal, T.S. Huttenga has recently presented a good overview of the discussions that have taken place.

At this moment we want to let this matter rest as it would take us too far away from our actual subject.

Omnipotence and Humility←↰⤒🔗

For our topic here it is important to realize that Christ proves to be almighty especially in his humility. If Christ had remained in heaven, he would not have shown that the winds and the sea obeyed him, neither would he have shown his power to the blind and the lepers. Then he would not have prayed to the Father at the tomb of Lazarus to be able to raise up his friend, and Lazarus would have remained in the grave. The Immortal became mortal and he, through whom all things came to be, became a man, a creature. But precisely because he was prepared to lay down his life and to be offered up in our place, he could prove to others that he was the Almighty.

After all, when was the omnipotence of God proven in a more wonderful way than when Christ, in deep humiliation, carried our curse on the cross. That is when he disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to shame, by triumphing over them (Col. 2:15).

Is God in Our Suffering?←↰⤒🔗

People have raised the objection to the classical confession of God’s omnipotence, that we would then regard God as the One who is the Unconcerned, who is enthroned high above this earth. In that case he would then rule everything and dispose all sorts of misery in this world, which we would then have to humbly experience and accept. However, we make a caricature of the matter when we talk about God’s omnipotence in such a way. The Scriptures do not reveal such a God.

However, the church has always rightly rejected that God himself, or the divine nature of Christ, would have suffered. That is the error of so-called theopaschitism. But equally, we insist that the Lord is not the cold, unmoved Agent of all things. Scripture at times expresses itself very strongly. In Isa. 63:9 it states that the Lord was afflicted in all the afflictions of his people. Of course, the eternal God, who inhabits an inaccessible light and who alone has immortality, is never anxious or distressed in the sense that we humans experience it. But the Lord sympathizes with the suffering of his people and we often read that he can no longer regard it. And precisely then the Lord showed his omnipotence. Because he was so moved with their lot, he led the people by his great power and brought them into the Promised Land.

About the Holy Spirit we read that he intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words (Rom. 8:26). The Holy Spirit, who is God, is also involved in and participates in the heavy struggle that the church has to contend with, and is thus unspeakably moved. But therefore, because the Spirit, who is God, is praying along, our prayer has such a tremendous power. The Holy Spirit did not remain safe in heaven with the Father and the Son, but he works vigorously in the midst of the churches.

Jesus also, who is now seated in glory and has a name above all name, is affected along with the church and prays with the congregation. He always lives to make intercession for us (Heb. 7:25). S.G. de Graaf went very far in talking about “the pain of God” in a sermon about Jer. 2:10-21, held in Amsterdam in the autumn of 1938. The title of the printed sermon is “God’s dismay at the people who abandon their God.” And we read in it, among other things, “Brothers and sisters, you do not find it strange that I am going to speak about God’s sorrow, or rather that we together want to hear God talk about his sorrow? We might object to conceding hurt to God. Then we should get rid of those objections, because the Scriptures speak of how it grieved him in his heart, and it is the Scripture that warns us that we would grieve the Holy Spirit. Whether you and I understand this does not matter. There is much more about God in the Bible, said by himself of himself, that we do not understand. Then we simply have to listen, so that it will penetrate in us” (S.G. de Graaf, ‘A prophet for the nations: Sermons from Jeremiah’ – Kampen, n.d.).

Jesus also, who is now seated in glory and has a name above all name, is affected along with the church and prays with the congregation. He always lives to make intercession for us (Heb. 7:25). S.G. de Graaf went very far in talking about “the pain of God” in a sermon about Jer. 2:10-21, held in Amsterdam in the autumn of 1938. The title of the printed sermon is “God’s dismay at the people who abandon their God.” And we read in it, among other things, “Brothers and sisters, you do not find it strange that I am going to speak about God’s sorrow, or rather that we together want to hear God talk about his sorrow? We might object to conceding hurt to God. Then we should get rid of those objections, because the Scriptures speak of how it grieved him in his heart, and it is the Scripture that warns us that we would grieve the Holy Spirit. Whether you and I understand this does not matter. There is much more about God in the Bible, said by himself of himself, that we do not understand. Then we simply have to listen, so that it will penetrate in us” (S.G. de Graaf, ‘A prophet for the nations: Sermons from Jeremiah’ – Kampen, n.d.).

We can certainly speak of God’s pain and hurt, yet it remains very different from our human feelings of suffering and pain. But God, who is so deeply moved and who carries sorrow about his people becoming renegades, is also the Almighty. He is able to establish a new covenant with that people. He is powerful to put his law within them and write it on their hearts (Jer. 31:33).

Different Views about God’s Omnipotence and Impotence←↰⤒🔗

Many people today prefer to talk about God’s powerlessness, i.e., his impotence, rather than about his omnipotence. Dorothy Sölle goes very far in this direction. She says, with an appeal to Bonhoeffer, that God is the impotent in this world and that God is allowing himself to be pushed out of this world, up to the cross (Sölle, ‘Christ the Representative: an essay in Theology after the “Death of God”’ – 1976). H. Berkhof, from whom originated the term “defenseless superiority,” speaks quite differently and also more biblically, even though Berkhof’s view is also not entirely without objections. God would be seen as retreating, to give us space in our rebellion against him. God would be like the Father who gives away his possessions to his rebellious son (Luke 15). That is what Berkhof wants to express with “defenselessness.” Yet this defenselessness is not a thing of powerlessness, but of superiority. Defenseless is the adjective while superiority is the noun. The superiority is the most important. God can withdraw because he knows that he will win. And so Berkhof wants to make a front on two sides: on the one hand he does not want to speak of God’s impotence. But on the other hand he reproaches especially the church that has taught – under the pressure of (according to him) a wrong concept of God with (too) great emphasis – the omnipotence of God. Because of this the church has inevitably become responsible for a lot of unnecessary feelings of resignation, rebellion, despair, and disbelief.

In addition, Berkhof says (and this is incomprehensible) that the expression “omnipotence” is used sparingly in the Bible, and if so then only in eschatological connections. Yet in the lives of the patriarchs and in Israel, God acted as the Almighty in the midst of their history, not just in texts that speak of the end times. And Berkhof misjudges things when he speaks of God’s defenselessness. When God withdraws, he is not defenseless, but he conquers his enemies. It is precisely in his extreme “defenselessness” that Christ has overcome death and hell. Therefore, it is not a false resignation that Lord’s Day 10 teaches us that in everything we will have a firm confidence in our heavenly Father.

Self-Limitation with God?←↰⤒🔗

Some have argued that God in his creation, and even more in his redemption of the world would have “restricted” himself. One of these proponents is J.H. Gunning. According to him, this concerns a “voluntary self-limitation” by God in creation, and this reached its apex at the incarnation. The big question is whether we can sustain this. God is indeed present in creation, and in the finite creature God’s glory and majesty can never radiate fully, but in his boundless glory God also remains outside and above creation (see Isa 40:12ff.). In the incarnation it is not the triune God but the Son who limits himself. He empties himself (Phil. 2:7). But even though Christ humbles himself, he remains God’s only begotten Son, and particularly on the cross Christ crushed Satan’s head.

A. Kuyper certainly also spoke in his Dictations in Dogmatics of a self-restraint of God in creation. But that did not concern God’s Essence, but the outward radiance of God’s majesty. Not only is the creation limited, but also our capacity for comprehension. If we cannot even fully know our fellow man or ourselves, how much less can we understand the infinite God? However, God himself continues to exist in all his glory.

A. Kuyper certainly also spoke in his Dictations in Dogmatics of a self-restraint of God in creation. But that did not concern God’s Essence, but the outward radiance of God’s majesty. Not only is the creation limited, but also our capacity for comprehension. If we cannot even fully know our fellow man or ourselves, how much less can we understand the infinite God? However, God himself continues to exist in all his glory.

There is much more that can be said about the omnipotence of God, also about what many have said or written about this in recent years. It is often the case that people attempt to bring the high and mighty God down to our level. And we can never speak of God’s omnipotence without also confessing his righteousness, holiness, his uniqueness and unalterability. Yet the reverence has gone missing with many speakers and authors.

The main thing is that we can continue to point to the Scriptures, that we confess a God, great in deeds, mighty to do all things. He is “unfathomable in understanding, and immeasurable in him compassion.” And the Mighty One of Jacob will also now redeem his people from all anxieties.

This article was translated by Wim Kanis

Add new comment