How Can a God of Love Use Violence?

How Can a God of Love Use Violence?

Violence in the Bible, especially in the Old Testament, is a stumbling block to many. That was indeed the case early in church history, and is even more so today. The Old Testament can be seen as the documentation of the origin of Israel and the Christian congregation: the Word of God for all ages. From this a believer draws comfort and strength; from this the church derives directives for faith and life. You would therefore expect to find words of love, light and life – not the language of violence.

Nevertheless, just a few pages after that beautiful beginning, it does come to that: revolution, manslaughter, vengeance and a destructive flood ... and so this continues right to the end of the Bible. Someone once did the maths and these figures are now floating around everywhere: the Old Testament contains 600 passages about murder, 100 texts in which God gives the command to kill, and 1000 passages that speak of God’s wrath, punishment and warfare. Blood flows plentifully in the Bible. From the blood of Abel that cries to the heavens in the first Bible book of Genesis, up to and including the call upon God to avenge spilt blood in the last Bible book of Revelation. Many Bible readers have already given up by this point. Shouldn’t the Bible be a sort of safe haven in this world in which we live, filled as it is with violence and misery? A book that points to a different world, the world of shalom and not the world of hamas (the Hebrew word for ‘violence’, all too well known these days in politics)?

Juridical Definition⤒🔗

The dictionary presents us with the following juridical definition of the word ‘violence’:

abuse of power, in which the rights of others are violated in a violent manner.

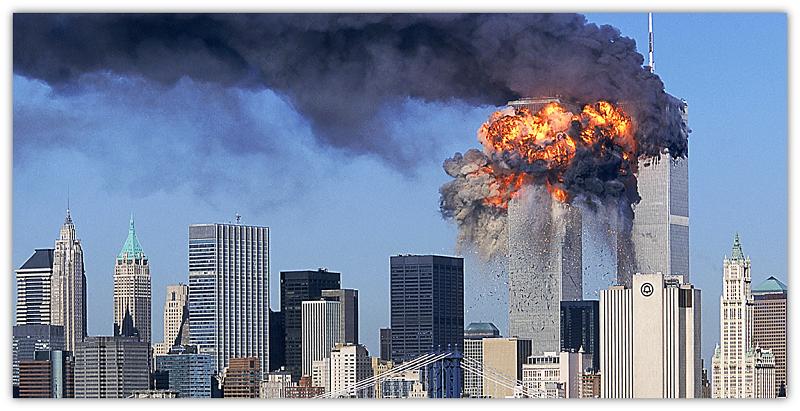

It is clearly a negative concept. To our sensibilities, violence, futility, and abuse of power all lie along the same track. In the past century we have seen so many examples that we have become sick to death of it: Verdun 1916, Hiroshima 1945, Rwanda 1994, New York 2001. Violence is, as it were, incorporated into our human society. Violent conflicts form a permanent factor that has to be reckoned with, on a personal level, socially, and worldwide. Is there a daily newspaper anywhere in which the word ‘violence’ cannot be found? Yet it is important to make a distinction between one sort of violence and the other. There is violence that is evil through and through, that seeks only its own interest and despises the other, but there is also contra-violence that has the intention of resisting evil, sticking up for the other, and restoring justice. The violence that the child-molester Dutroux used on his victims was of a very different character to the physical violence used by the police at his arrest. Of course, in the havoc of human existence things often get terribly intertwined. Yet in practice we cannot get around this fact: there is evil violence and there is liberating violence. Violence that serves the world of hamas, and violence that serves the world of shalom.

When we also come across that whole spectrum of violence in the Bible, should we, in a certain sense, not be glad that this is the case? Whom would it serve to have a Bible filled with wisdom and devout redemptive reflections that stand removed from our daily reality? Life is multi-coloured, raw, and sometimes bewildering. In this life, natural violence, and social, military, religious and political violence all play a great role. The Old Testament addresses this everyday reality, the texts focussing on a God who goes his own way with his people, in this real world, with a deep passion for justice and peace. A God therefore who, in extreme cases, also makes use of violence. Wrongdoing is not taken lightly; people are held responsible; the dimension of violence is not concealed. What a joy it is for all those who have been marginalized and trampled on in our world history that the God of the Bible also – yes, especially so – concerns himself with violence. That means, in the words of the theologian Kuitert, that the bully will not have the advantage over the victim forever.

The Ground Rule←⤒🔗

In the meantime, it is important that we see the violence theme in the Old Testament in the right proportions. Though it is clear that violence is fully present in the Old Testament, the actual question is how, and in what connection, this violence emerges. Sometimes the Old Testament, after some selective treatment of the ‘awkward texts’, gets quickly set aside as a problematic and primitive book. Painting a distorted picture is a lot easier than doing justice to the whole of the Old Testament. When reading this book in all fairness, one cannot miss the ground rule of justice and peace. God has created the world as good, and he did not let go of that world after sin had driven a schism through all creation. Against all the evils of greed and decay he is working towards a world of shalom: in the Old Testament via his people Israel, and in the New Testament via his son Jesus Christ. In this way he (speaking in New Testament terms) ‘makes his kingdom come’. His first utterance to go out over this creation was ‘let there be light’, and that will also be his last word. In between both these words, he shows us the way, and leads us out of the dark towards the light, because of his incomparable love for man. However, in order to come to a world of shalom, God sometimes, in this broken world of hamas, has to make use of violence: contra-violence to curb the evil, to punish and cast out. Indeed, contra-violence is and remains a form of violence, but it is necessary because evil usually cannot be stopped by words, however alluring or angry those words may sound.

The Old Testament makes it clear that this kind of violence is only safe with God. Violence in the hands of people very quickly gets out of hand. Surprisingly enough, the Old Testament itself, despite its reputation as a book of violence, brings a far-reaching message of anti-violence. This is especially noticeable when we make a comparison between religious literature from the ancient world around Israel. In Assyrian royal inscriptions or Ugarit mythology, forceful power is sometimes raised to a level of the highest virtue. In the Old Testament, however, violence is never glorified. On the contrary: human violence is unmasked as a great evil at the very beginning, in the history of Cain and Abel (Gen. 4). In order to curb the spread of this evil, God gives the brother-murderer a sign: God himself will act as judge over whoever injures Cain. In this story, which could be seen as a window on world history, God’s contra-violence is mentioned for the first time. Jesus’ statement that “all who draw the sword will die by the sword” (Matt. 26:52) resonates on a broad soundboard in the Old Testament literature of wisdom. Everywhere this wisdom warns against the folly of violence and the lust for power. In Old Testament law, clear boundaries are set around the violence of retribution, for example, in the well known ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’. In the society of that time, in which revenge was without limitations (as with the figure of Lamech in Gen. 4, who brags that he will revenge himself 77 times for every injustice done to him), this rule came as a blessing from heaven: just one eye for an eye and only one tooth for a tooth.

Discouraged←⤒🔗

In all sorts of situations in the Old Testament, human violence is discouraged. It is striking how often the kings of Israel and Judah are severely criticized by the prophets for their use of violence. The prophet Nathan, for example, reprimanded David, the pre-eminent king and founder of the Judaic royal dynasty (2 Sam. 12). This David, chosen by God, was not permitted to build a house for God because he was ‘a man of blood’. Such criticism was unheard of in the world of the Ancient Near East. There the founder of the dynasty was by definition always the founder of the temple.

The longing for a world of shalom gains ground especially in the prophecies of the future. The Old Testament does not preach a call to conquer the world by force, but rather that the law will go out from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem, and that the people will then come to find shelter under God’s judgment.

They will beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore. Isaiah 2

A stirring vision is that of the kingdom of peace in Isaiah 11, with images of predatory and tame animals grazing together, and of a child that plays at a snake’s den. Psalm 46 sings of what God is doing on earth: ‘He makes wars cease to the ends of the earth. He breaks the bow and shatters the spear; he burns the shields with fire. He says, “Be still, and know that I am God!”’

Our Perception of God←⤒🔗

The fact that the Old Testament contains a clear anti-violence message does not solve the problem of violence in this book, but puts an even greater strain on it. For how does this message relate to various passages in which, to our sensibilities, excessive divine violence is exerted, or in which people are called upon to destroy others? Examples are plentiful: the Great Flood over the whole earth, the downfall of Sodom and Gomorrah, the wiping out of the people of Canaan and Amalek, frightening prophecies of judgment, terrible curses of hatred. If God is a God of love, surely this cannot be! Is this not in contradiction to the biblical ground rule that we sketched previously? Many Bible readers find that the questions simply multiply. Whoever looks for answers to these questions should do so in all humility. For these are not the sort of questions, that can be met with clear solutions and well-balanced arguments. The demonic reality of evil is too great for that, and the God of the Bible is not to be fathomed. Of crucial importance here is that we are prepared to test our own perception of God critically against the biblical image of God.

It cannot be denied that, in the past century, farreaching changes have taken place in modern western thinking about God. This has been referred to as a metamorphosis in the perception of God. Clearly an end has come to unproblematic talk of God’s vengeance, God’s judgment, and God’s wrath. The combination of God and violence evokes embarrassment and resistance in many people today. The perception of God has faded somewhat, become milder, softer and lighter. The call to break with authoritarian perceptions of God from the past is heard everywhere: away with the depressing and slavish images of God as Lord, King, Judge, Warrior! The accent on God’s compassion, love and grace must prevail. Some even speak of a ‘therapeutic’ God image. That very well suits a culture that gives priority to the assertive human with his independent freedom of choice and self-realization. Collective thinking, such as is found in many cultures and also in the Bible, has become strange to us. The individual has become the norm and the starting point in our thinking. The accent lies on positive emotions and experiences, and a prosperity-ideal of abundant enjoyment and the exclusion of all disturbing factors. Faith must comply with man and his own experiences. In this context, what would you want with a God who ruffles your feathers, demands surrender, conversion and obedience – a God who sometimes even punishes and exterminates a complete nation in his wrath?

Part of the Trouble←⤒🔗

No doubt these developments play a part in the trouble we have with the violence passages in the Old Testament. Where former generations of Bible readers had few problems with this issue, we do have them: our reading glasses have changed. It can therefore be refreshing to listen to the biblical interpretation of Christians in non-western traditions, who often appear to view the problems in a very different way. They too acknowledge the central message of God’s love and forgiveness, but they will be less inclined to place this in opposition to biblical notions like revenge and judgment. How does a Tutsi whose family has been slaughtered by Hutus read the Old Testament testimony of God’s judgment prophecies? How does a Cambodian who wears the scars of the Khmer Rouge era in his flesh read the curses uttered in the Psalms? We can stay closer to home and listen to the Yale University theologian Miroslav Volf, a Croatian who in the nineties was a witness to the violence in the Balkan wars. He writes:

One, then, could object that it is not worthy of God to wield the sword. Is God not love, long-suffering and all-powerful love? A counter question could go something like this: Is it not arrogant to presume that our contemporary sensibilities about what is compatible with God’s love are so much healthier than those of the people of God throughout the whole history of Judaism and Christianity? (...) Recalling my arguments about the self-immunization of the evildoers, one could further argue that in a world of violence it would not be worthy of God not to wield the sword; if God were not angry at injustice and deception and did not make the final end to violence, God would not be worthy of our worship.’ (...) The only means of prohibiting all recourse to violence by ourselves is to insist that violence is legitimate “only when it comes from God” (...) My thesis that the practice of nonviolence requires a belief in divine vengeance will be unpopular with many Christians, especially theologians in the West (...) Soon you would discover that it takes the quiet of a suburban home for the birth of the thesis that human nonviolence corresponds to God’s refusal to judge. In a scorched land, soaked in the blood of the innocent, it will invariably die. And as one watches it die, one will do well to reflect about many other pleasant captivities of the liberal mind.1

Deeply anchored in the Old Testament is the confession of the compassionate God who is love, and who therefore can rise so ardently to anger (Ex. 34). Both sides of this basic confession – God’s holy love and Gods holy wrath – dominate history. The picture that the biblical testimonies paint of God takes us to the reality of life. Following through on the question of the purpose of the violence texts in the Old Testament, we come up against the unfathomably deep intensity of evil, injustice, arrogance, repression and lust for power. God, who loves justice and righteousness, does not remain unmoved when it is violated. He takes the man who commits injustice in his actions completely seriously and holds him responsible for his deeds. In these passages we meet a zealous God who in his holy wrath unmasks and judges all evil. Inside him is a deep aversion to all that is at odds with the goodness of his creation. A powerful longing for peace, justice, and destruction of the darkness speaks from this. There has truly been a battle fought since the breach at the beginning of humanity, when God spoke to the serpent in paradise:

And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head, and you will strike his heel.Gen. 3

The Completely Different←⤒🔗

The violence passages in the Old Testament open our eyes to who the God of love also is, and who we are as humans. God is the completely Different, who truly takes action both in word and deeds. Thanks be to God – for in the everyday reality of a world in which the devil and fate, hatred and death are constantly making their move, a God with-clean-hands would be completely out of the game. The God of the Bible can do awesome things, horrible things to us humans. But never randomly and unpredictably. He does not practise violence for the sake of violence, as is the case in many a literary text about the gods in the worlds around Israel. In some way or other his ‘violence’ always has to do with his aversion to evil, sin, and revolt. His intervention foils the triumph of the lie. God’s violence stands in a broader frame: that of his justice. Time and again, his violence serves the restoration of justice and peace.

In this lies comfort for the numerous destitute and deceived in our world history.

My soul yearns for you in the night; in the morning my spirit longs for you. When your judgments come upon the earth, the people of the world learn righteousness.Isaiah 26

All the more do we understand how powerfully deep God’s love is, who gave all to save this world. Grace, reconciliation, justification, new life – all those great words in the Bible glow even brighter when we see that God is a holy God, working his way right through our world of hamas to his world of shalom.

Genocide? Vengefulness?←⤒🔗

Yet it still troubles us when we stumble across passages in the Old Testament that, on first reading, are hard to digest: infamous passages we continually carefully steer clear of in the Sunday sermons. Two of the most well known are the command to exterminate the Canaanites in Deuteronomy 7, and the proclamation of hatred in Psalm 139. Now it is true that genocide is a crime against humanity, and inciting hate has rightfully been made a penal offence in our country. What is to be done with a Bible in which these things are documented? What we should do with the Bible is, foremost: read carefully, listen patiently, judge fairly. The command to kill seven nations in Canaan is horrifying indeed. “Repayment by destruction” is what Deuteronomy 7 calls this. It brings to mind the Muslim fanatics’ jihad. But is it that? It is noticeable that God’s command in Deuteronomy 7 is unique: only there and only then was Israel commanded to do this. Only to these seven nations, and not to arch enemies like Edom or Philistia (apart from Amalek, but that is a different story altogether). Only at that one moment in history and never again. When you read this text in its broader context, you notice that this command to exterminate is connected with two issues: firstly with God’s deep disgust with Canaan’s wickedness, and secondly with God’s exclusive love for Israel.

With the Canaanite nations, something special was going on. As early as Genesis 9, in the story of Noah’s drunkenness, we see that after Ham’s misbehaviour, it is not Ham himself but his son Canaan who is mentioned in the ensuing curses. In Genesis 15, God speaks to Abraham about Israel’s long stay in Egypt: only the fourth generation was to return to Canaan ‘for the sin of the Amorites (a collective name for the Canaanites) has not yet reached its full measure’. In many other passages also, for example Leviticus 18 and 20, or Deuteronomy 9, 12 and 20 the gruesome injustice and idolatry of the Canaanites nations is brought to the fore. Apparently, these nations, notwithstanding the years of God’s patience following his promise to Abraham, had hit rock bottom in their immorality and godlessness. God wished to protect his people against this. He loved his people, with whom he had made his covenant, too much. Through this people God determined to put into effect his purpose for the world: ‘for you are a people holy to the LORD your God. Out of all the peoples on the face of the earth, the LORD has chosen you to be his treasured possession’ (Deut. 14:2). Nothing and no one was allowed to come between him and Israel, especially not the evildoing Canaanites’ temptations. The land of Canaan was to be a dwelling place in which God and his people could live together in safety. Israel was not to be contaminated by the moral and religious filth of the original inhabitants.

This has nothing to do with ethnocentrism, but everything to do with the holiness of God’s people. Were the Israelites to yield to temptation and themselves commit the same atrocities, then God would not spare them, but strike them with the same excommunication. This is exactly what took place in the events of history. For Israel did not drive out most of the Canaanite nations, and subsequently succumbed to the charms of the ‘Canaanite’ way of life, surrendering to idolatry and violence. The end results of this downhill slide were the exiles into Assyria and Babylon: the land ‘spat out’ the people. Israel itself suffered the fate of the Canaanite nations, as had been the case with Sodom and Gomorrah beforehand, and even earlier with the great flood. God, as it were, partially brings forward in time the Great Judgment, in order to put an end to the evil right then and there. Not that it pleases him to do this:

For he does not willingly bring affliction or grief to anyone.Lament 2

But with this contra-violence he prevents evil from running rampant uncurbed.

Psalm 139←⤒🔗

Just as troubling to our ears as the exterminating command in Deuteronomy 7 is the curse from Psalm 139: ‘Do I not hate those who hate you, LORD, and abhor those who are in rebellion against you? I have nothing but hatred for them; I count them my enemies’. What is the psalmist saying here? His song swoops us up into a high flight: God sees all, knows all, knows us completely. In accordance with this the poet proclaims his dependence, and says that he belongs to God totally. To accentuate this last statement, he confesses – wholly in the language of the Old Testament – that he does not at all belong with the godless, and ‘hates’ them. This entails a total commitment to God and a heartfelt aversion to the world of evil, and of the “bloodthirsty”. These are not his personal enemies, but God’s enemies: observe the order in the text. It is a type of confession in a negative mode. However paradoxical it may appear, this hate is not in opposition to the biblical ethic of neighbourly love, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

In Psalm 139, someone is speaking who is part of God’s covenant people. In Old Testament times, God’s way with this world is characterized by a unique concentration on this one people of Israel, among whom he wished to live. It was all cutting edge history here. God had made his covenant with Israel. In the world of those times, it was customary to confirm a covenant with a series of blessings and curses. So it is with the ‘treaty text’ of God’s covenant with Israel, see for example Leviticus 26 or Deuteronomy 28. With his ‘hate’ against God’s enemies, the poet is latching onto God’s own covenant curse upon the godless. God himself hates all who do injustice, and despises all who deceive and shed blood (Psalm 5), ‘...but the wicked, those who love violence, he hates with a passion’ (Psalm 11). As God’s covenant people, Israel had the holy duty to hate evil, and cast off uncleanness and godlessness. Evil was not to gain a foothold in Israel (Psalm 140). By standing completely on God’s side, the poet of Psalm 139 makes a choice for the world of blessing and goodness, truth and justice. This poet does not take justice into his own hands, but with his prayer places everything in God’s hand. When reading such a proclamation we should also take into account that the Old Testament believer had barely any view of the life after death that we now have. Nor did he know of a judgment day at the end of world history in which God would ultimately do justice. Therefore, with a curse he calls upon his God to intervene here and now and show his justice. For it is unimaginable to him that godlessness should have the last word in his reality...

Not Same Manner←⤒🔗

The aforementioned means that we would not be able to pray this sort of prayer today in the same manner that Israel did. But to condemn these prayers from the world of the Old Testament would be short sighted. The kernel of it, the longing for justice and peace, remains essential up to today. You can taste in it something like in the book Star Children by the Jewish author Clara Asscher-Pinkhof. After she has described how, in the middle of the night, the grinning SS soldiers of Westerbork transit camp drove a group of hundreds of frightened little children into the train, the train to Auschwitz, she continues:2

O, but they will avenge themselves! Whether they are alive or not – they will avenge themselves! They will not let the cry from their toothless little mouths be silenced, the complaint from their wide open eyes be covered up till the end of times! No rest will there be for all who perpetrated this – no peace for those who dragged infants from their cherishing homes and smote them onto one deadly heap – no rest, no peace, as long as the echo of those children’s outcry and the reflection of those complaining eyes have not been silenced. They are powerful, these defenceless. Their power reaches to the end of the world, to eternity.

The Difference←⤒🔗

The church has always maintained that the Old Testament is God’s Word. This does not speak for itself: because of its violent passages, a cry arose to do away with the Old Testament. Marcion gave vent to this cry in the second century after Christ in his book Antithesis (‘contrasts’), in which he makes a huge contrast between the Old and New Testament, and between the God of the Old and of the New Testament. To him, violence and revenge stood completely opposite to peace and reconciliation and love. With all sorts of variations, many follow his track right up to today, speaking of a contradiction between Old and New Testament, although seldom so radically as Marcion. That does seem a logical conclusion, if you juxtapose a curse from the Psalms right next to Jesus’ prayer on the cross. And you could claim to detect some kind of reproach against all the violence in the Old Testament in Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount (‘love your enemies’, Matt. 5). Some scholars speak of a two-track policy in the Old Testament: on the one side you have the language of violence, on the other the language of peace. The latter gains strength through the ages, and the New Testament follows that line. Yet this image does not do justice to the testimonies of the Old and New Testament. For nowhere do the New Testament authors criticize the Old Testament. They take it as their starting point, as the authoritative Word of God, as Jesus himself did. They readily quote from the imprecatory psalms. Jesus himself uses the language of violence in his parables and in his warnings against Hell. At one point he compares himself with a king who will have his enemies destroyed before his eyes (Luke 12). In the Book of Revelation the Lamb and the Lion are the same person. God is a consuming fire, as Hebrews 12 quotes from Deuteronomy 4. The thesis can easily be defended that the New Testament is even more serious about judgment and condemnation than the Old Testament. In the New Testament it becomes manifestly clear that God’s wrath extends over the entire world (John 3:36; Rom. 1:18). Moreover, God’s judgment here gains a greater depth because it can be called ‘eternal’ – up to and including the terrible prospect of Hell.

No Contradiction←⤒🔗

Between the Old and New Testament we see no principal contradiction, but we do see a clear difference. Undeniably, we read less about violence in the New Testament than in the Old Testament. And the New Testament preaches with more emphasis on reconciliation and love toward the enemy. Not because God’s image in the New Testament has changed, but because there God’s way with his people and this world has changed, and with a very far-reaching change at that: in the person and work of Jesus Christ. In him, the world of shalom broke through definitely; the kingdom of God began. It broke through the boundaries of Israel, and spread out into the whole world. No longer is there the unique concentration on Israel alone, but God reaches out to everybody with his gospel. In Jesus’ death and resurrection, God’s justice comes to light in the ultimate manner. In Jesus’ death on the cross – which was extremely violent – he reconciles us humans to God. To save people, God himself brought the offering of his love. The great judgment on evil came down on Jesus; he bore God’s condemnation in our stead. All who trust in Jesus are saved – but whoever rejects his Word awaits the judgment on the Last Day. In the intervening period in which we now live, the time of God’s patience (2 Pet. 3), the gospel is being spread worldwide. The gospel proclaimed by Jesus is not an opposing voice that partly disqualifies the Old Testament, but it gives voice to the new, decisive phase in the coming of God’s kingdom in this world.

Hereby the church does not wield the sword, but the weapon of prayer. No longer (as in Israel in the Old Testament) do the state and church come together in one nation, with the necessity to execute violence. Violence is not an instrument used to realize the ‘salvation-state’, the kingdom that has come in Christ – no indeed, the church fights with the Word. This does not set aside the fact that, according to the New Testament, as far as the ‘constitutional state’ is concerned, God can make use of human violence to curb evil: the sword has been entrusted to the government (Rom. 13 and 1 Pet. 2). Therefore the church, while praying for the government and committing everything into God’s hands, awaits the day that God’s world of shalom will break through for all eternity (Rev. 19).

Add new comment