Development of Church Polity in the Netherlands

Development of Church Polity in the Netherlands

The Reformers of the sixteenth century learned from Scriptures about how the Lord wished His church to conduct her affairs. Characteristic of Calvin's understanding of the Lords will in relation to church government was the central place given to the elder. So it was said that "Calvin checkmated the Pope with the pawn of the elder."

Ironically, the concept of church government which Calvin gleaned from the pages of Scripture did not get off the ground in Geneva where Calvin lived. His thoughts instead found fertile soil in the reformed churches of Scotland, France and the Netherlands. Tragically, historical developments in France in the years after the Great Reformation virtually snuffed out the Reformed Churches in that country. Reformed church polity on the European continent, therefore, came to its own in the developments in the Netherlands. It's to this country that we now need to turn to see continental reformed church polity in practice.

Background History⤒🔗

The effects of Martin Luther's reformatory work in the sixteenth century were felt not only in his native Germany. Also the Netherlands benefited much from Luther's rediscovery of the gospel. However, agreement with the reformer's teachings often went at the cost of one's life. Already in 1523 the enmity of the devil against the truth of Scripture resulted in the first victims being burnt at the stake. Despite the persecution, though, the Lord saw to it that the good news of the gospel took root in the hearts of many in the Lowlands of North-west Europe. Yet, by the providence of God, in the passage of time it was not so much Luther's emphases that were embraced and believed, but Calvin's.

In 1545, Guido deBres, at the age of about 24 years, came into contact with the Gospel and became a believer. His choice for the gospel did not come at a cheap price, for the Netherlands were under Spanish rule and so the state religion was Roman Catholicism. Under the ruling hand of King Philip II of Spain persecution against the Protestants was intensely fierce during the 1550s. DeBres, as preacher of the Gospel, was compelled to do his work secretly; he worked underground and under a false name. In 1561 deBres completed his Confession and had it thrown over the wall of the regent's home. By so doing, DeBres wished to make clear to the king that the Protestants were not a group of radical upstarts. His aim in writing his Confession was "to protest against this cruel oppression, and to prove to the persecutors that the adherents of the Reformed faith were no rebels, as was laid to their charge, but law-abiding citizens who professed the true Christian doctrine according to the Holy Scriptures" (Book of Praise, p.440).

Article 36 of the 'Belgic Confession' serves to prove that deBres and all others who embraced the Reformed faith were not rebellious against the government. In this article deBres confessed what God's Word has to say about the place of the civil government in society, what its task is and how it must be honoured and respected by all. Writes deBres,

Moreover, everyone – no matter of what quality, condition, or rank – ought to be subject to the civil officers, pay taxes, hold them in honour and respect, and obey them in all things which do not disagree with the Word of God. (Book of Praise, p.470)

That is quite a statement to make concerning a government at whose hands deBres and his fellow believers suffered such intense persecution. Disobedience to the civil authorities was only warranted when one was compelled to act contrary to the demands of Scripture.

God's demands in Scripture included also (deBres learned from reading God's Word) that God had given principles concerning how He wants His Church to be governed. Despite the intensity of the persecution and the dangers of living as reformed churches, deBres considered obedience to God on these points essential. So it was that he included the basic principles of church government in the Confession he prepared. We find deBres' thoughts on church government in Articles 30-32. Says deBres:

We believe that this true Church must be governed according to the Spiritual order which our Lord has taught us in His Word. There should be ministers or pastors to preach the Word of God and to administer the sacraments; there should also be elders and deacons who, together with the pastors, form the council of the Church. By these means they preserve the true religion.

DeBres went on to confess what God revealed in His Word about how office-bearers receive their office.

We believe that ministers of God's Word, elders, and deacons ought to be chosen to their offices by lawful election of the Church, with prayer and in good order, as stipulated by the Word of God. (Article 31)

Again: We believe that, although it is useful and good for those who govern the Church to establish a certain order to maintain the body of the Church, they must at all times watch that they do not deviate from what Christ, our only Master, has commanded. (Article 32)

Let us bear in mind that such church government was directly contrary to the wish of the authorities of deBres' day: it was not the congregation but the government who determined who would serve as priest in a town; ministers were not permitted to preach or teach, public worship was not permitted, elders could not bring home visits. Yet deBres saw need to confess what God revealed on the point – and to teach it to his congregations also.

In 1566 fanatical Protestants set out to destroy the contents of Roman Catholic churches, particularly the images, pictures and altars. Numerous reformed people, also of deBres' own congregation, rushed into the streets to sing psalms, and gathered in the fields to hear the preaching of God's Word. This all prompted a reaction on the part of the authorities who came down with a very heavy hand. Many Protestants were imprisoned, including deBres himself. In 1567 he was hung on the gallows. As part of the same crackdown, the King a year later sent his general, Alva, into the Netherlands. This very able general crushed the uprising. Hundreds of thousands of people fled, to France, Germany, and England, forming refugee congregations in foreign cities as Wezel (Germany), Emden (Germany) and London (England). The Church suffered greatly and the churches in existence at the time came to be known as 'the churches under the cross' – they were a church persecuted, and a church scattered to wherever refuge could be found.

Here we have people relatively new to the Reformed faith. One would expect that in the above circumstances many would fall away from the Reformed Faith (and indeed, some did), and that physical survival would be uppermost in their minds. But that was not the case for the majority! Here we see the power of faith at work. If Christ is King, they confessed, the political situation of the day need not be cause for depression. With Christ on the throne, the future need not be viewed as only dark. A general as Alva could rule the Netherlands with an iron fist. Yet the believers were confident that the Lord in His good time would let the Gospel flourish in their country. Despite the difficulty of their situation the brethren at the time were optimistic.

That is also why the brethren risked their lives to meet together in order to develop Scripturally justifiable church government that could be put in place when the Lord granted freedom from persecution. It is a point most worth noting: the fathers did not consider ecclesiastical assemblies, i.e., classes or synods, to be a 'pain in the neck' or a necessary evil.

Even in time of persecution they considered such assemblies to be essential to the life of the church of Jesus Christ, so essential that they risked their lives to develop reformed church polity. The fathers knew it: the churches needed each other so very, very much.

Despite persecution from the authorities, the fathers considered a reformed manner of governing the church a Scriptural imperative. So, despite the dangers of the times, the fathers set about formulating a Church Order agreeable to God's Word.

The Convent of Wezel, 1568←⤒🔗

Directly after Alva crushed the Dutch resistance to Spanish rule, a group of reformed brethren from the Netherlands met together Wezel, Germany. (In Wezel there was freedom of religion, though Alva's spies were everywhere no doubt). This particular meeting was called 'The Convent of Wezel'. (The word 'convent' means to convene, to meet). It was not a classis or a synod, for it was not made up of delegates from the churches. Rather, this meeting was the private initiative of interested persons who set as their agenda the preparation of an official synod. They understood that in order to get a synod organised there first had to be a federation of churches. So they set out together to lay down some principles as to how a federation of churches ought to function. In attendance were refugees from the Netherlands who had found shelter in the cities of Wezel (Germany), Emden (Germany), and London. Though driven from their homeland, they were motivated by love for God and His church to lay the ground work for reformed church government in the Netherlands.

To establish reformed church government, these brethren saw no need to 're-invent the wheel'. Calvin had already dealt with the matter in Geneva and wrote a Church Order entitled 'Ecclesiastical Ordinances'. The brothers in Wezel used these Ordinances as a blueprint for their work. However, rather than just accept these Ecclesiastical Ordinances on the merit of Calvin's authorship (Reformed as he was in his thinking), the brothers saw it as their responsibility to see if Calvin's work could be improved in any way. So they developed Calvin's work further. This action in itself is interesting in relation to Reformed Church Polity. Important as Calvin's contribution (and Bucer's too) is to reformed church government, 'Reformed' is not so much 'Calvinistic' as 'Scriptural', and therefore always needs to consider the question "what does God want of us?"

The brothers in Wezel, then, made improvements to Calvin's 'Ecclesiastical Ordinances'. In as much as we stand here at the cradle of Dutch church polity, we may consider Wezel's changes to be essential principles of continental reformed church government.

Principle 1: No Lording over Others←⤒🔗

Present at the Convent of Wezel was a gentleman belonging to the refugee church in London, by name of Moded. This Moded had been sent by London to Geneva, to seek advice in a matter of difficulty in that congregation. The matter of difficulty related to the minister; Rev van Wingen of the London church was an inflexibly dominant character. The brothers present at the Convent of Wezel read Jesus' words in Matthew 23:8: "But you, do not be called 'Rabbi'; for One is your Teacher, the Christ, and you are all brethren." (The word 'teacher' in the above quote denotes a leader or master.) The implication was surely that in a church of Jesus Christ there is no room for domineering: a minister is not to lord over another minister, nor a minister over a consistory, nor a consistory over another consistory, nor an elder over another elder, etc. Rather, all office-bearers have a place directly under Christ, and so the one office-bearer needs to respect the other. Those present at the Convent of Wezel recognised this to be a Scriptural principle basic to healthy church life, and so penned as Article One for their Church Order:

No church shall in any way lord it over other churches, no office-bearer over other office-bearers.

Reformed church polity serves to protect congregations and consistories from domineering individuals.

Over the years, this stipulation has moved from the beginning of the Church Order to the end because this is where it fits best in view of the overall structure of the Church Order. This change in location, however, in no way belittles the importance of the principle. No lording over others is very much a fundamental principle characterising reformed church polity.

Principle 2: The Need for Ecclesiastical Assemblies←⤒🔗

A second principle which Wezel underlined was that the churches need to meet regularly. We have already examined the doctrinal basis for churches federating together and interacting with each other within a federation of churches. There is, however, also a practical justification for federating together and interacting in a bond. For regular interaction between the churches by means of assemblies serves to prevent both hierarchy and independentism. Rev van Wingen's congregation in London was rather isolated from the other churches, and such isolation can give a minister opportunity to lord it over his consistory. If churches in a federation seldom or never meet with each other, there is also a very real tendency for each to go its own way in matters such as liturgy, policies in relation to church discipline, beliefs. Churches within a federation have a very real need to meet together and to discuss things, for after all, don't they all serve the one Lord, and should they therefore not also be united in the way in which they serve Him?

The article adopted by the Convent of Wezel reads as follows:

since… it shall be most beneficial to achieve and maintain uniform agreement in doctrine as well as in regulating ceremonies and discipline, we consider that, as much as possible, frequent meetings of neighbouring churches ought to be organised. So that each arising item can be discussed at such meetings, we consider that all efforts must be made to divide the various Dutch provinces into fixed classes. In this way each church will know with whom she must interact and consult about the more important matters which, by her judgment, affect die common interest.

It is intriguing that the fathers at Wezel expressed desirability for the churches to meet together "frequently.”

In fact, the articles of the Church Order they adopted, specify that churches in a local area ought to meet as often as once every three months; such frequent meetings would promote "uniform agreement in doctrine as well as in regulating ceremonies and discipline," and so counter hierarchy and independentism.

We need to note that this goal was expressed in an environment of persecution, and in a time when distances were generally covered by foot. Contrast that to the context of our church life: we enjoy freedom of religion and have the conveniences of road and air travel available to us. Yet as churches we meet together only once every two years!

On this point we have deviated far from what the fathers advised. As a result we face a spirit of independentism amongst our churches and the differences between the churches of our federation are real. When all is said and done, this is a self-inflicted problem. Let us meet together much more often, and when we meet let us spend our time talking first of all about matters relating to work within the federation of churches. Let it be fixed in our minds: each church within the federation needs the others.

Notice too that the fathers did not leave it up to the individual churches to decide with whom each might meet and talk and so cross-fertilise. "Fixed classes", said the fathers, ought to be formed, so that "each church will know with whom she must interact and consult." The churches had one Lord, one faith, one hope, and so each church must feel comfortable to speak with the neighbouring church – even if there were differences in emphases. In this way, too, uniformity "in doctrine as well as in regulating ceremonies and discipline" would be achieved and maintained.

From Wezel to Emden←⤒🔗

Marnix of St Aldegonde, a man of royal blood who had quite a standing in government circles, worked underground to free the Netherlands from the Spaniards. This man was Reformed in his thinking, and scriptural in his love for the Lord and the brethren. He saw that by the grace of God the Netherlands would one day be free, and that the churches had to be ready for that event.

By his judgment, it was imperative that there be adequate preachers of the gospel available to make the most of the window of opportunity that would arise in the day of freedom. But to train capable men required the combined effort of the churches. Similarly, Marnix was convinced that since there is one Lord and one faith, the people of the land needed to be united in their belief and consequently the churches should also be unified in doctrine, church discipline, liturgy and ceremonies. In order to achieve this, Marnix saw that it was of paramount importance that the churches meet and discuss together – a Synod was required, yet no Synod could occur as long as the churches were not federated together in some way. Marnix, therefore, did what he could to encourage the growth of a federation of churches.

At this time already, though, two lines of thinking existed with regard to church polity. On the one hand there was a group of liberally minded people who favoured Erastian (government-centred) church polity. This group (they became the eventual supporters of Arminian theology) saw no need for churches to form federations. Rather, if guidance was required by a church, it should turn to the government. On the other hand there was also a desire for Reformed (elder-centred) church polity. Marnix was convinced that the Reformed line was the correct direction for the churches to take and to that end he encouraged the convening of a synod in Emden.

The Synod of Emden, 1571←⤒🔗

The first General Synod of all the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands was held not in the Netherlands, but in Germany, in the town of Emden, in 1571. This synod was held outside of Holland because persecution was still a very real thing. However, despite the dangers of meeting together, the fathers did so in obedience to the Lord and m recognition of their need for each other. The churches sent delegates to Emden to meet together in order to assist each other as churches and to defend themselves against heresy. There they officially formed a federation of churches.

One would expect that at this first official meeting of the churches, the churches would busy themselves immediately with matters pertaining to church polity. It is striking that instead their first item of business was that each delegate (and in them each church) made a point of expressing agreement with the Belgic Confession. Note: to date the Belgic Confession had been accepted by various churches on their own accord, but not by the churches altogether; this was the first meeting of the churches together. The fathers recognised the need for a confession, not just for churches individually, but also as a bond of churches. After all, what essentially binds churches together? It is the one faith which God has worked in the hearts of His people; faith in the one Gospel of salvation through the one Saviour Jesus Christ. This unity of faith required expression before a Church Order could be finalised. And a Church Order in turn could not be remote from the Confession of the Churches, but had to be built upon that Confession.

After the churches together came to agreement on what their one common faith was, the fathers moved on to develop a model for Church life. The Synod of Emden built on the work done in Wezel, as well as the experiences and decisions of the French churches. The French churches, we should know, had not suffered much persecution during the 1560s, and so had opportunity at a number of synods to develop a church order. This concept was the best Church Order the Synod of Emden could find, and so it was used as a basis and model for Emden's Church Order. Just like the Convent of Wezel, so too the Synod of Emden made it their business to modify this model in order to spell out for themselves principles of Reformed Church Government. For example, an article about no lording over others (not found in the French Church Order) received pride of place in Emden's Order. A second article notated the need for agreement with the common confession. Further, Emden changed the repeated use of the word 'church' in the French Church Order to the plural 'churches' – thus providing a Scriptural corrective to the widespread idea that the local churches were but chapters of the one big, real church.

The Synod of Emden also adopted another article, which reads,

These articles, which regard the lawful order of the church, have been adopted with common accord. If the interest of the churches demands such, they may and ought to be changed, augmented or diminished. However no consistory or classis shall be permitted to do so, but they shall endeavour diligently to observe the provisions of this Church Order as long as they have not been changed by synod.

This article too points up how the fathers treasured Reformed thinking. Churches promise to accept decisions of Synod not because some higher body made them, but rather because the churches themselves in Synod made the decisions "with common accord", i.e., together.

←⤒🔗

←⤒🔗

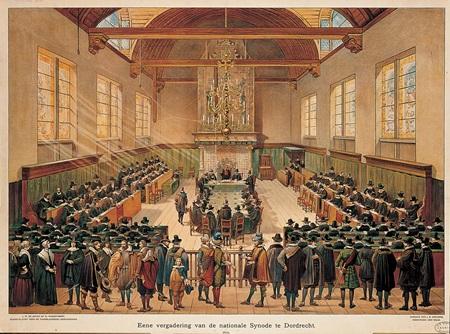

The Synod of Dort, 1618/19←⤒🔗

Persecution in the Netherlands ended in 1572. Thereafter, church life developed rather quickly. After the Synod of Emden the churches held their synods on Dutch soil. Of importance for the development of the Church Order, mention should be made of the provincial Synod of Dort in 1574, the national synod of Dort in 1578, the synod of Middelburg in 1581, and the synod of 'sGravenhage of 1586.

Each one in their own way, these Synods built further on the work done by Wezel and Emden. Essentially, though, the Church Order stayed much the same over the years as that adopted by the Synod of Emden. The Synod of Dort 1618/19, after having dealt with the heresies of Arminianism, worked on the Church Order that had developed so far, and adopted a version that has become known as the Church Order of Dort. Our Church Order is in principle the Church Order of Dort – and hence is rooted in the work done in Wezel and in Emden.

Add new comment