Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) A Reformer beside Zwingli and Calvin

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) A Reformer beside Zwingli and Calvin

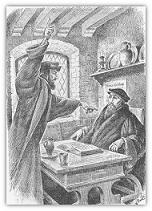

Guillaume Farel – who does not know him from that dramatic account of his first encounter with Calvin? The young author of the Institutes, on his way to Strasbourg, is sworn by the fiery preacher Farel by God Almighty to develop his talents beside him in Geneva for the much-needed building up of the recently “reformed” church.

Farel – until recently he was noted as the author of the first book on Reformed dogmatics; it was thought that his book Sommaire dated from 1524-1525. Recent research, however, has shown that this book was published only in 1529. With this it lost its status as “first,” because Zwingli’s Commentarius appeared earlier, in 1525. Perhaps Farel’s name will continue to be associated with the fact that he was the first to write and publish a French Reformed liturgy, Manière et fasson.

Farel – until recently he was noted as the author of the first book on Reformed dogmatics; it was thought that his book Sommaire dated from 1524-1525. Recent research, however, has shown that this book was published only in 1529. With this it lost its status as “first,” because Zwingli’s Commentarius appeared earlier, in 1525. Perhaps Farel’s name will continue to be associated with the fact that he was the first to write and publish a French Reformed liturgy, Manière et fasson.

Less well known is the fact that in 1553 Farel – although he was no longer a minister of Geneva at the time – received the task to guide the heretic who had been condemned to death, Michael Servetus, and to accompany him in his last hours before his execution in Geneva (October 27, 1553).

Farel’s active life encompasses the first period of the age of the Reformation; it was demanded of him to determine the course of the church as pure as possible. He deemed only one compass to be necessary in this, the Holy Scriptures, a fact that establishes him as a Reformer beside Zwingli and Calvin.

Gradual Conversion to Sola Scriptura⤒🔗

Little is known about Farel’s youth. Born in southern France in a small alpine town of Gap (Dauphiné) – now almost 500 years ago – in a devout Roman Catholic notary family, destined by his parents for a military career, the twenty-year-old Guillaume Farel makes instead a conscious choice for studying at the university in faraway Paris. It ends up being twelve years that lead to a spiritual climax: his main mentor is no one else than the famous Lefèvre d’Etaples (1455-1536) who established his own theological institution separate from the Sorbonne, where in a “humanistic-reforming” manner, study of the Bible is made. In the same time as when Luther discovers in Wittenberg that the salvation of sinners takes place only by God’s grace, Faber Stapulensis (the Latin name of the great teacher) makes it clear to his student and friend that there is nothing that is meritorious in man himself.

In the meantime it is not altogether certain that there has been any direct influence from Luther on the group surrounding Faber Stapulensis. The risks are great – certainly in France – but aside from this it was possible in those years to study the Bible independently and therefore to arrive at similar reformational insights.

In later years Farel noted how he had been busy for a span of three years (!) praying to God “that he would show me his grace to understand the right path.” During this time Farel studied the New Testament with great zeal.

Farel did not easily become detached from Rome. The authority of the church and the traditions of the ecclesiastical teaching magisterium, held together in “the papacy,” remain in force for him for some time. The lives of the saints continue to offer sufficient pious experiences. And there remains also the power of Aristotle’s logic, highly valued by Rome. It all looks so indispensable. However, Farel witnesses later that God showed him mercy and that he started to see his errors and … “then my spirit, guided by all sorts of circumstances to him and having thus found the harbour, attached itself entirely and only to him. Since then all things have gained a new perspective: Scripture is better known, the prophets have been opened up more, the apostles were made clearer, and the voice of Christ was recognized as the voice of the shepherd, the master and guide; insight was gained that there is access to the Father through no one but Jesus.”

Thus all kinds of (apparent) certainties now make room for the only certitude there is for people: only the Word of God – sola scriptura!

The break with the Roman Catholic Church takes place in 1521. Farel departs for Meaux where bishop Briçonnet (also a student of Faber Stapulensis) strives for a reformation in a “biblical-humanistic” spirit. In this “reforming” environment he is appointed as preacher. But when the bishop, in spite of all his reformational ideas, does not break with Rome, Farel leaves – after a fiery sermon against the veneration of Mary. He travels to the area where he grew up, but here he finds such lack of understanding and opposition – also with his own relatives – that he finally ends up seeking refuge in Basel, via Meaux and Paris.

A Collision Course with “Balaam” – Erasmus←⤒🔗

The 16th century Basel is a town with a wide-open heart: refugees from all over Europe are welcome here. The university appears to bathe itself in the light of the great humanist Erasmus, who chose to live in that town. His (Greek) edition of the New Testament of 1516 comes from a printer in Basel.  Writings from Luther are also published here. The Reformation in Basel gets more and more opportunities when in 1523 the town government charges the preachers to proclaim “the pure gospel” from here on in (in Zürich that cooperation was granted to Zwingli in the same year). Johannes Oecolampadius (1482-1531) is since 1522 already very involved with reformational activities – as teacher and professor. Farel finds lodging with him. Soon he also meets there with the rector of Utrecht, Hinne Rode, who together with the lawyer Cornelis Hoen from The Hague pleads for a symbolic doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. They influence Farel in such a way that later in the struggle between Luther and Zwingli over the meaning of the Lord’s Supper he will choose the position of the latter.

Writings from Luther are also published here. The Reformation in Basel gets more and more opportunities when in 1523 the town government charges the preachers to proclaim “the pure gospel” from here on in (in Zürich that cooperation was granted to Zwingli in the same year). Johannes Oecolampadius (1482-1531) is since 1522 already very involved with reformational activities – as teacher and professor. Farel finds lodging with him. Soon he also meets there with the rector of Utrecht, Hinne Rode, who together with the lawyer Cornelis Hoen from The Hague pleads for a symbolic doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. They influence Farel in such a way that later in the struggle between Luther and Zwingli over the meaning of the Lord’s Supper he will choose the position of the latter.

Farel’s own activities in Basel focus particularly on a public debate in the spring of 1524. With his defense of the thirteen reformational propositions, Farel manages to create a breakthrough into the university, where he is allowed to give lectures on the Pauline epistles. The practical value of these academic lessons apparently is so exceptional that no one less than Erasmus begins to be concerned about the disturbance of the peace in the church. In 1524 Farel turns with great vehemence against the “prince of the humanists” (Erasmus) who is continuously waiting to make a radical choice. He describes him as a chameleon, an obnoxious opponent of the gospel, even as a “Balaam”! The collision between the Reformation and humanism came to a head here in Basel!

A meeting between these two men brought no solution. The town government now decides that Farel has to leave Basel.

His new place of residence is not far away from Basel: the small town of Montbéliard (in German: Mömpelgard), where Duke Ulrich von Württemberg grants him permission to preach in the chapel of the castle. With great zeal Farel goes to work. But after only a few months the highest ecclesiastical and secular authorities take such drastic measures (of discipline) that Farel decides to return to Basel.

From there he then establishes himself in 1525 in Strasbourg. Very important here are the contacts with the reformational leaders Wolfgang Capito (1478-1541) and Martin Bucer (1491-1551).

In the meantime Farel has published an exposition on the Lord’s Prayer, entitled Loraison, and he endeavours also to spread the writings of Zwingli throughout France.

In November of 1526, Farel receives a new work assignment: under the auspices of the city of Berne he will begin to work in the western Swiss town of Aigle, as teacher and preacher, for the reforming of the church. Here, in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the main work of Farel is being done. First for some time in Aigle, then a few years later in Lausanne, followed by Neuchâtel. In those years you could characterize Farel as a travelling evangelist in service of the Reformation. In 1528 he is present at the religious conference in Berne, after which this canton officially chooses to join the side of the Reformation. Farel is the author of the French protocol of this important dispute.

At times Farel needs to be warned by friendly colleagues against his great fanaticism. Of course they know his character: with thundering voice he can lash out at idolatry and superstition. He is able to provoke his hearers to such an extent that the people’s anger even turns against him. E. Doumergue pictures for us the scene that Farel is always prepared to take up the battle … “in the graveyard, in the marketplace, in the streets, at one time being carried along by the enthusiastic people on a pulpit in the church, and another time being beaten half dead by those who did not want to listen to his speech. At Ollon women mistreated him. At Bevaix the prior and the monks force access into the church while he is preaching and they chase him off after having beaten him severely. At Saint-Blaise the pastor incites the people against him and Farel is so badly mistreated that he arrives in Neuchâtel eviscerated, exhausted, and spitting up blood, almost unrecognizable.”

Farel’s Witness of Faith←⤒🔗

Between all his other activities, Farel manages to find the time to work on a Dogmatics handbook. It does not end up as a scholarly exposition with scientific arguments, but as a book of faith for the “laity,” the common people. It is also well suited to serve as a “conversation piece” for travelers on their way.  It is the Sommaire, which in forty-two chapters provides a succinct overview of “that which every Christian needs in order to put his trust in God.” (The full title is: “Summaire & briefve declaration dauicuns lieux fort nécessaires à ung chascun chrestien pour mettre sa confiance en Dieu et ayder son prochain”)

It is the Sommaire, which in forty-two chapters provides a succinct overview of “that which every Christian needs in order to put his trust in God.” (The full title is: “Summaire & briefve declaration dauicuns lieux fort nécessaires à ung chascun chrestien pour mettre sa confiance en Dieu et ayder son prochain”)

On the title page is printed “Turin …1525,” but no printer in Turin had been involved with it and the year of publication is also incorrect. A deception? According to recent research by Francis Higman, the book was published in 1529 at Alençon. With the incorrect place and year the many enemies got lost and placed on the wrong track – and until recently also his proponents.

When we accept that the Sommaire was “only” published in 1529, a strong argument was added to the suspicion that Farel, in writing this dogmatics, made use of Zwingli’s Commentarius. Research by G.W. Locher shows, in addition to Farel’s independent opinion, also a substantive unity with Zwingli’s beliefs; and not just on the doctrine of Lord’s Supper.

From the following citation of the Preface of the Sommaire we can get an idea of how Farel experiences the unique-historical aspect of his time:

“Now God makes his light to shine to lead us out of the darknesses that were heavier than they ever were in Egypt … God’s Word offers the means to salvation … To understand Scripture, the light of the Spirit of Jesus is needed.”

From the Waldensians to Geneva←⤒🔗

In September 1532, a general synod of the Waldensians came together in Chanforan, in the valley of the Angrogna (presently northern Italy). These much-maligned and oppressed “Protestants before Luther” have become rather familiar to Farel through two of his students, who had come into contact with these Christians in the Alps. In 1532 this leads to an invitation for Farel and two other Swiss brothers to take part in the Synod of Chanforan. The Waldensians decide at this ecclesiastical meeting to join the Reformation. It gave great pleasure to the Swiss. It was also decided – under influence of Farel – to strive for a French translation of the Bible from the original languages. The Bible that was in use had only been partially translated and was incomplete. Farel’s argument for a new translation sounds very convincing: “for the sake of God’s honour and as the best weapon against error.” The task of translation is given to Pierre Robert Olivétan (or, Olevitanus), a nephew of Calvin, who is known as having a good mastery of Hebrew and Greek. In a remarkably short time – in 1535 already – he comes through with a complete new translation of the Bible.

The influence of Farel is also noticeable in other matters that were discussed at the synod. He urges the Waldensians to a more radical anti-Roman attitude, which must show in the refusal of the confessional, of fasting, and of the prescribed feast days. Farel also emphasizes the doctrine of free grace, which forbids any thought of human merit.

The influence of Farel is also noticeable in other matters that were discussed at the synod. He urges the Waldensians to a more radical anti-Roman attitude, which must show in the refusal of the confessional, of fasting, and of the prescribed feast days. Farel also emphasizes the doctrine of free grace, which forbids any thought of human merit.

On his return trip to Switzerland Farel and his companions stay for some time in Gap, his place of birth. In this period three of Farel’s brothers, Gauchier, Claude, and Jean-Jacques, joined the Reformation after years of earlier opposition. However a judge’s verdict results in them losing all their material goods.

Guillaume Farel’s trip meanwhile leads him to Geneva. His contact with fellow believers is noted immediately and the authorities pronounce that the three travelers must leave the city within one hour, on pain of death.

Yet it will not be long before the same city opens its gates for the fiery Reformer of western Switzerland.

The political situation in the 1530s becomes increasingly difficult. Both the bishop of Geneva, who has his residence outside of the city, and the Duke of Savoy want control of the city (again) with all their might. The city is put under siege. For the preservation of Geneva’s independence there is support from the city of Berne, which is also interested to extend its political power. This city is reformational since 1528, and Geneva will now also be confronted with this. After the preacher Froment extended his pastoral care over Geneva, Farel can continue his work in the winter of 1533-34 in the still-besieged city of Geneve. The hunger, cold, and various illnesses cause the citizens of Geneva to realize the seriousness of their situation. But how powerful are Farel’s sermons for these people in need. And above all: how the peoples’ hearts, inclined to licentiousness, are persuaded to give themselves entirely to the true service of God!

The elections of 1534 make it clear that three of the four mayors have now broken ties with Rome. However, being free from Rome does not mean Geneva is reformational; Farel realizes that very well. And yet he receives more cooperation from the Council of the city for his preaching. Beside Farel the very capable Pierre Viret (1511-1571) may also serve the church, which becomes more and more Reformed.

Turbulent scenes arise in the summer of 1535: after a failed dispute becomes the occasion of commissioning a church building for evangelistic services, an iconoclasm follows in the cathedral of St. Peter in August of the same year. It is fortunate for the reformational movement that prominent citizens are leading this. Soon the mass is abolished. And when through a military action Berne manages to get the city out of the Duke of Savoy’s power, the Genevan cause turns altogether in favour of the Reformation. The elections of 1536 provide the city with four Protestant minded mayors (one of whom is a staunch supporter of the Reformation). And in a special plebiscite of Sunday, May 21, 1536, on Farel’s initiative, it is decided and sworn that “we all by the aid of God desire to live in this holy evangelical law and Word of God, as it has been announced to us, desiring to abandon all masses and other papal ceremonies and abuses, images and superstitions, with all that may pertain to this, and wanting to live in union and obedience to justice…”

Not even two months after this transition to the Reformation, a young Frenchman, Jean Calvin, enters the gate of Geneva. He will have an encounter that he had not counted on: with Rev. Guillaume Farel.

Calvin in Geneva←⤒🔗

Farel gets immediately into action when he learns the almost unbelievable report that the author of the Institutes has come into town. In the inn where Calvin wanted to spend the night, the Genevan pastor speaks extensively about the urgent situation of his congregation. But when Calvin reacts in a dismissive way to the pastor’s request to stay,  Farel displays an imposing dynamic to move the heart of the young Frenchman. With near-divine persuasiveness Calvin is pledged to use his capacities in the service of the Genevan church. He no longer dares to refuse. That is how Calvin becomes God’s servant – he dedicates his heart to the service of the gospel, toward the upbuilding of God’s church. Now as teacher in a Swiss town, soon as pastor (via letters, books, and academy) in many countries of Europe.

Farel displays an imposing dynamic to move the heart of the young Frenchman. With near-divine persuasiveness Calvin is pledged to use his capacities in the service of the Genevan church. He no longer dares to refuse. That is how Calvin becomes God’s servant – he dedicates his heart to the service of the gospel, toward the upbuilding of God’s church. Now as teacher in a Swiss town, soon as pastor (via letters, books, and academy) in many countries of Europe.

Farel is the man to help the cause of the Reformation, as soon as possibilities present themselves. In light of this we should also note his activities for and at the Disputation of Lausanne in October 1536. About ten propositions will be the topic of discussion there, and one of the drafters is Farel. According to G.W. Locher the propositions are a “document of Zwinglian theology.” The purpose of the dispute is not an open-ended discussion, but it must bring about the decision – by the government – for the Reformation in Lausanne. Farel defends, together with Viret and supported by Calvin, the reformational theses convincingly. The result is then also that Lausanne moves to join the side of the Reformers in the Eidgenossen (Confederation).

In Geneva, meanwhile, the licentiousness of the citizens again raises its ugly head and the government does not show a steady course in regard to the church. The tensions result in the expulsion of Farel and Calvin in 1538.

Active until the End←⤒🔗

Soon afterward Farel receives a call to Neuchâtel, well known to him, where with some interruptions he served the church until his death in 1565.

He is continuously active, for example, in Metz and its surroundings, where he is almost killed in 1542 when the congregation is raided by an armed band.

During a visit to Geneva in 1553 – when Servetus is to be judged – he is unexpectedly tasked to accompany the condemned man to the place of his execution. Did they perhaps foster some hope that Farel would succeed in changing the mind of the man who denied the Divine Trinity? It does not help, however much Farel tried in all sincerity.

Farel undertook many attempts to come to greater unity with Protestants in other areas of Europe. However, his ideal of one large community of faith for Lutherans, Zwinglians, and Calvinists was never realized.

In his 69th year Guillaume Farel marries a widow who had fled the persecution in Rouen. A son, born six years later, dies at a young age.

In May of 1564 Farel bids farewell to the dying Calvin. Although he himself is twenty years older, he survives the Reformer of Geneva. In a letter he pens the sad lament, “Oh, if only I had departed in his place, while he, such a useful servant, would be healthy and well to still serve the churches of our Lord for a long time.”

One year later Farel’s strength declines as well, and he dies on September 13th 1565, at the age of 76. His body is buried in the chapel of the cathedral of Neuchâtel.

The significance of Farel lies especially in the fact that he had been an instrument in the hands of the Lord of the church to shine forth the light of the gospel in many places in western Switzerland and the southern part of France. Through his intervention, Calvin was pulled away from his pure academic studies to the pastoral practice in Geneva. Farel had been instrumental in strongly involving the Waldensians with the reformation of the church, and to a certain extent he had helped to lift their isolation. From a theological perspective the position of Farel can be regarded as an important link between Zwingli (who had died in 1531) and Calvin (who afterward as a man of the second generation took upon himself the leadership of the Swiss-French Reformation).

The significance of Farel lies especially in the fact that he had been an instrument in the hands of the Lord of the church to shine forth the light of the gospel in many places in western Switzerland and the southern part of France. Through his intervention, Calvin was pulled away from his pure academic studies to the pastoral practice in Geneva. Farel had been instrumental in strongly involving the Waldensians with the reformation of the church, and to a certain extent he had helped to lift their isolation. From a theological perspective the position of Farel can be regarded as an important link between Zwingli (who had died in 1531) and Calvin (who afterward as a man of the second generation took upon himself the leadership of the Swiss-French Reformation).

Central in the life of Farel and Zwingli and Calvin are the golden words: Deo honor – honneur à Dieu – Gott die Ehre – all honour to God. This confession makes each human heart humble and ready to sacrifice his life.

Add new comment