Equipping for Ministry: Characteristics for Ministry Training in the Asian Context Ministry in an Asian Context

Equipping for Ministry: Characteristics for Ministry Training in the Asian Context Ministry in an Asian Context

The topic assigned to me is sufficiently broad and vague enough to allow me to explore it from various angles. I have developed this paper, for the most part, as a practical reflection rather than as a theoretical research paper.1 Some of these reflections are based on my experience as a theological educator and administrator in India for over twenty years. Further, I had the privilege of giving leadership to the work of the Asia Theological Association (ATA) as the Chairman of its India chapter for several years.

ATA is the leading evangelical theological accrediting agency in the region, with about a hundred institutions as members at present. As chairman of the India chapter I had the opportunity to observe “training for ministry” in colleges in India and some other neighbouring countries. On the other hand, my involvement with the Reformed Presbyterian Church of India, especially with our Presbytery’s Candidates and Credentials Committee, has helped me to look at ministry training from the other side, that is, from an ecclesiastical perspective. I trust that the comments and suggestions offered here will be beneficial to all of us in our ministry in the Asian context.

This first part of my paper looks at our context. It is significant that we are gathered for a regional conference. Therefore we need to pay attention to the particularities of our Asian context in which we minister and for which we are called to equip leaders. Following this, we will examine the nature of ministry in Asia. What is the ministry for which we are training people? In the second part of this article, in response to our context, and on the basis of our identity as those belonging to the Reformed tradition, we will ask what are or ought to be the unique characteristics of ministry training.

1. The Asian Context⤒🔗

It is debatable whether we can talk of the Asian context, as if Asia is a monolithic entity. Asia, as we know, is an immense continent with a number of political nations, cultures, languages and religions. The variety and immensity (in terms of area and population) make it difficult for us to generalise.

General Context←↰⤒🔗

A well-known Asian theologian reduced the Asian context to its religiosity and poverty. Of course, this is an oversimplification. However, it does touch the two basic aspects that comprise the Asian context, its religious and economic realities. For our purpose here, we need to see the factors involved in a more concrete way. Training for ministry must seek to become relevant to these factors in order to be effective. The following are some of these factors.

Religious Pluralism←↰⤒🔗

Asia, as we all know, is the birthplace of the major world religions of our day. Religion has always played a significant role in private as well as in public life. This fact has many practical implications. Our people are religious at the core. In contrast with secularised nations in other parts of the world, religious beliefs, feelings, and expressions are respected (for the most part). This situation also means that ours is a mission context. It is inevitable that we will encounter people of other faiths; training for ministry is training for mission.

Cultural Pluralism←↰⤒🔗

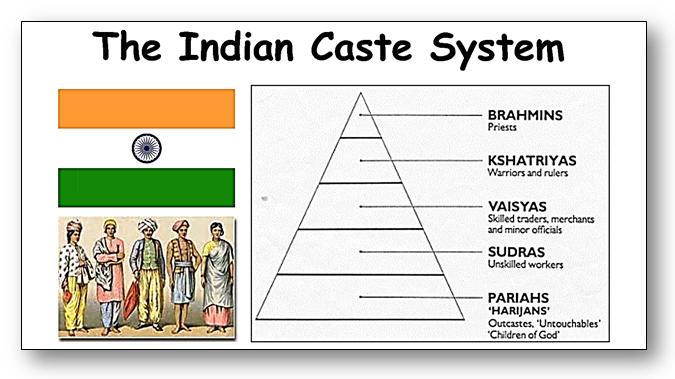

Numerous ethnic and language groups inhabit Asia. Sometimes they are integrated into political units such as nations. At other times they simply exist within the same borders with no integration, and conflicts between these groups is not uncommon. Ethnic and other identities are a problem for the church and ministry as it is for society at large. When these identities are stronger than our common identity in Christ, the very concept of Christian ministry is affected. It is a challenge to those who are involved in ministry-training as well. Should we encourage church planting according to the “homogenous unit principle” (along caste, tribe, ethnic lines) or should we seek to develop churches that more adequately express the spirit of reconciliation expressed in the gospel?

Population←↰⤒🔗

Asia is an enormous continent. The two most populous nations, India and China, for part of it. While a large population may have certain benefits, it also presents a number of challenges for ministry. Careful thought needs to be given in planning mission strategies to reach out to such large groups of people. Equally careful planning has to be made to disciple and nurture those who turn to Christ. The amount of resources needed in terms of finance and personnel is simply staggering.

Revival of Traditional Religions←↰⤒🔗

While for a period in our history the strand of religious reform was prominent, this is no more the case. Whatever the reason for its emergence, revivalism is in full swing. This is certainly true in Hinduism and Islam, and may be true of other religions such as Buddhism and Sikhism. The pull of reform and modernity has not been strong enough to overcome the forces of tradition.

Militant Fundamentalism←↰⤒🔗

Beyond revival, religious fundamentalism has a militant, aggressive dimension. It is questionable whether fundamentalism breeds militancy or is extra to it. Though part of a world-wide phenomenon, the effect of militant fundamentalism is perhaps felt more in Asia than elsewhere. This is due to an explosive combination of socio-economic (poverty, illiteracy, unemployment), political (ethnic and narrow identities) and religious factors present in Asia.

Globalization←↰⤒🔗

The effects of globalization, both positive and negative, are strongly felt in Asia. There is also strong resistance to globalization, at least to some of its aspects, in certain quarters.

Disparity between, the rich and the poor←↰⤒🔗

In spite of general improvements in economic indicators, the gap between the rich and the poor has not yet been bridged.

Shame-oriented←↰⤒🔗

Asian cultures, on the whole, are more shame-oriented than guilt-oriented. This is evidenced by the high number of suicides, honour killings, etc. as well as a by strong adherence to caste/tribal and other sub-identities. Alienation from one’s sub-identity is considered serious.

Authoritarian←↰⤒🔗

Although the situation is changing, vertical or hierarchical authority structure is very strong in Asian communities. Subordinates find it hard to question or challenge decisions and opinions of their superiors such as parents, elders, pastors, and civic leaders.

Legalistic/Moralistic←↰⤒🔗

By this is meant a rigid and simplistic application of rules of conduct irrespective of the complexity of the situation. A strong sense of discipline, with both positive and negative consequences, is characteristic of Asian societies. Another aspect of this is the emphasis placed on duty or obligation rather than doing what is morally right or gracious. An example of this is the doctrine of nishkamakarma (desireless action) in Hindu philosophy.

I point out that these characteristics are, to an extent, inter-related. It must further be kept in mind that the above is, of necessity, a generalization. It must not be thought, however, that the above description is not applicable to Christians and churches. We live very much in the society at large, and share with it, to a greater or lesser extent, the distinguishing values (good and bad) of the Asian context.

Church Context←↰⤒🔗

In addition to the above, Christians and churches in Asia share certain special features. These also are relevant for training for ministry and mission.

Minority←↰⤒🔗

In most countries, Christians are a minority, sometimes a very negligible minority. Our minority status brings with it certain social/psychological anxieties and attitudes. A minority complex can lead us to inaction and defensiveness. The overarching concern becomes that of maintaining what we have rather than to engage the society with the gospel. Mission and ministry are compromised as a result. Although we can empathise with this attitude, I think all of us will agree that such an existence in fear is contrary to our calling as followers of Christ.

Persecution←↰⤒🔗

As a consequence of religious revival and the rise of militant ideologies, persecution of Christians is growing in many Asian countries. Persecution is a reality in several states of India. The sad part is that incidents of violence against Christians are under-reported. What is worse is that the sympathy which ordinary Hindus had towards Christians has more or less vanished. Champions of Hindutva are involved in coordinated propaganda wars against Christians. The attacks against Christians are allegedly in response to Christian insistence on converting people holding other beliefs and Christian condemnation and ridiculing of Hindu gods, religions and practices as pagan or uncivilized. Christians in Islamic or Buddhist contexts may face a similar situation.

Low Social and Economic Status←↰⤒🔗

Although there are pockets of influence and power, Asian Christians come from a lower socio-economic background with resultant consequences. It is well-known that the large majority of those who turned to Christ in the nineteenth century mission effort were from the lower castes. The trend is still the same today. Except where Christians form a sizeable group or where they are influential, they are also subject to discrimination and exploitation. These result in special problems within the church. Because of the lower caste (dalit) identity, Christians as a whole are looked down upon. What is even more shameful is that discriminatory and exploitative practices in society are perpetuated within the church as well, contradicting its testimony to the power of the gospel to set people free. Worldly strategies for control are employed in the church and result in power struggles, especially where the teaching of the gospel is minimal. Many from the lower classes and castes are unable to assert authority or assert it irresponsibly. Due to lack of previous education, discipling these new believers in the Christian faith is an uphill battle. These are some of the manifestations of social realities in the church. While I have described the Indian situation particularly, I suspect parallel situations can be found in other countries.

My attempt here to elaborate on the Asian context (both in society and in the church) is due to the conviction that “equipping for ministry” is context-specific. Borrowing and re-planting programmes simply won’t do. Evangelical theologians have recognised the significance of the context not only for theology but also for theological education. In June 1983, the International Council of Accrediting Agencies (ICAA; now known as International Council of Evangelical Theological Education (ICETE)) of the World Evangelical Fellowship – Theological Commission (WEF-TC) formulated a “Manifesto on the Renewal of Evangelical Theological Education.” This Manifesto, consisting of twelve “affirmations and commitments,” was adopted by the ATA as “values esteemed” by this agency.2 Contextualization, which was given first place in this list of values for theological education, may be quoted here in full:

Our programs of theological education must be designed with deliberate reference to the contexts in which they serve. We are at fault that our curricula so often appear either to have been imported whole from abroad, or to have been handed down unaltered from the past. The selection of courses for the curriculum, and the content of every course in the curriculum, must be specifically suited to the context of service. To become familiar with the context in which the biblical message is to be lived and preached is no less vital to a well-rounded program than to become familiar with the content of that biblical message. Indeed, not only in what is taught, but also in structure and operation our theological programs must demonstrate that they exist in and for their own specific context, in staffing and finance, in teaching styles and class assignments, in library resources and student services.3

Reflected in the above statement is a shameful and painful admission that traditional theological education has not adequately addressed the issues of our context. It is a sad fact that the average graduate of a theological institution may know more about the expansion of Christianity in Europe than in his own native place. A student may have a good understanding of how the early church tried to state who Jesus Christ is in the context of Gnosticism and Greek philosophy. It is a disconcerting thought that the same student may never have reflected on how to communicate Jesus Christ to Hindus or Muslims. These are some of the concerns behind the discussion on contextualization and theological education.

2. The Nature of Ministry in Asia←⤒🔗

Ministry in Asia is as complex as the Asian situation itself. By juxtaposing four sets of realities in tension, I would seek to bring out the various dimensions and understandings of ministry. We would seek to do this both with reference to the Asian context as well as with reference to biblical teaching.

Service versus Prestige←↰⤒🔗

It will not be incorrect to say that the term and the concept of “ministry” have acquired certain respectability both in the church and in society. In public life a “minister” is a highly placed official, who wields power and has many under him to attend to his every need. (As someone once remarked, a minister is a civil servant who is neither a servant nor very civil.)

In the ecclesiastical sphere also, the ministry is considered a respectable profession. This is especially so in our western history ever since the emergence of Christianity as a dominant religion. In Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, the dignity of the office is linked especially with the theology of sacraments, while in the Protestant tradition it is especially linked with the preaching of the word and the minister as an educated professional.

We are aware of the fact that any idea of social respectability is something extra to the biblical concept of ministry. This is not to deny that in the Bible, the office of a pastor or teacher is a dignified one. Indeed, in the Bible we find exhortations to honour those who labour in the Word. But certainly in the first century this had not been translated into social respectability.

It is important for us to remember that in the New Testament, ministry is a “blood-and-sweat” term, rather than something denoting white-collar respectability. Scholars tell us that the very idea of “service” was something despised in the Greco-Roman world. It was the Christian faith that elevated service to a high status. Paul describes his own ministry (and that of others) using words such as “labour” and “toil,” terms that are associated with manual work. Not only the terms, but even the analogies used for ministry remind us of its physicality. In the Pastoral Epistles, ministry is compared to the work of athletes, farmers and soldiers – all professions requiring physical exertion, discipline and single-mindedness. It is also pictured as extremely rewarding.

Ministry, in many parts of our continent, is still considered lowly and despised. With the influence of dominant models of ministry (such as the mega-church with a super-pastor model) growing in Asia, the situation will likely change. It will be tragic if the image of the minister as a spiritual leader and servant is replaced with that of a CEO of a corporation.

In most of our contexts, the pastor is expected to be fully involved in the problems of the people. He is expected to find jobs for the unemployed, suitable matches for young people to marry, take those who are sick to the hospital, and be an interpreter and advocate for those who are in trouble. In urban and affluent congregations, the situation may be different. Whether or not these properly belong to the work of a minister, equipping for ministry cannot ignore the realities of the field.

Maintenance versus Mission←↰⤒🔗

There is a greater and growing awareness in Asia that ministry is not just maintaining (or consolidating) a congregation, but also engaging the world. In more traditionally Christian places and in certain churches, maintenance receives priority. The context in which we exist, as described above, encourages us to be mission-oriented in our ministry. In India mission compounds survive as vestiges of our past history. Also, there are certain villages and towns which claim to be fully Christian. But the large majority of Christians live and work among people of other faiths, and interaction with them on a daily basis is unavoidable. Once again, this picture of our existence is truer to the New Testament pattern of the chosen of God living as aliens and strangers in the world. The question is whether the church will recognise God-given opportunities and exercise its God-given mandate for mission.

If the people of God are to engage in mission on a daily basis and in the normal contexts of interaction, they should be intentionally prepared for such encounters. Otherwise, the tendency will be to exist side by side without interaction, or worse, seek the security of own ghettos.

Professional versus Popular←↰⤒🔗

Another area of tension in the understanding of ministry can be described as that between the professional and the popular, or between the clergy and the laity. There has been much re-thinking on this aspect in recent days.

Traditionally and historically, a minister is thought of as a seminary-educated professional. That picture is probably true even today. Traditional ministry training also followed a certain pattern. Theological institutions emerged from and were modelled after the university model, which had a heavy academic content and professional orientation. In more recent days, ministry and ministry-training have come under serious criticism, re-examination and evaluation. Structured, formal programmes offered by theological institutions have been found wanting by many. Underlying this criticism, among other things, is the question, who are to be trained for ministry? Is ministry training the same as equipping professionals? Or, is it equipping the people of God, the laity? This is a crucial question that has become prominent in the last half a century. The emerging consensus is that ministry belongs to the whole people of God rather than to a few professionals.

Peter Pothan, associated with extension education for many years, gives three good reasons why lay people should be trained theologically. First, it is the lay people who are in the world. They need to be equipped for witness in the world if the gospel is to spread. Second, it is the lay people who do most of the ministry in the church, such as Sunday School teaching, VBS, Women’s Fellowship, etc. Derek Tan, a Singapore-based Pastor and theological educator who was General Secretary of the Asia Theological Association until his recent demise, agrees with this assessment. He explains that lay training is urgent because “in today’s church, a large slice of the ministry is carried by the laity.”4 Third, it is the job of the pastor to train all the believers to do the work of the ministry and be not deceived by false teachers.5 The last point gives a theological basis for seeing ministry as belonging to the whole people of God. This idea is based especially on a new understanding of Eph 4:11, and it conforms to the patterns of apostolic ministry that we see in the Bible. Citing Ephesians 4:7-16, Brian Wintle, General Secretary (ATA-I) and New Testament scholar, argues that the work of ministry must be undertaken by the whole people of God. In the body analogy employed in that passage, the leaders correspond to muscles and sinews and have the responsibility to facilitate and co-ordinate the working of the members.6 While we need to safeguard and hold in high regard the dignity of the offices, we also need to see that ministry and mission are enterprises of the whole church. Paul is keen on defending his apostolic office, but counts a large number of men and women among his co-workers. He refers to the whole church as “partners” with him in the ministry of the gospel. The manner in which the gospel spread in the early church points to a high degree of involvement by ordinary believers, in other words, the laity. Even in the Great Commission of Mt 28, the emphasis is not on sending professionals, but on the church as it goes about. Professionalization is necessary for various reasons, and is justifiable. But professionalization should not eliminate or replace the mandate given to the people of God as a whole, nor should it be considered essential to the biblical concept of ministry. It will be obvious that such an understanding of ministry will have consequences for the task of equipping.

Ritualistic versus Reformational←↰⤒🔗

In much popular understanding ministry is thought of as the correct performance of certain rituals. The Medieval Church, with its faulty theology of the sacraments, made the correct performance of sacraments the most important responsibility of the priest. Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches continue this emphasis today. But it will be wrong to think that the idea of ministry as the correct performance of rituals is something that belongs exclusively to these churches. Many Protestant churches also see ministry in this manner, and the function of the minister not only as administering sacraments, but attending to other communal rituals – blessing homes, performing marriage, etc. In India, pastors are often called priests, and an equation is made between them and the poojaris of the Hindu temple – those who assist in the performance of rituals.

It is well-known that the Reformation corrected the false theology of sacraments and restored the preaching of the Word as the central task of ministry. This Reformational understanding of ministry is something very desirable in our time and in our context. The purpose of Christian mission and ministry is to draw people to Christ and to build them up in the faith so that they may become mature. This is something that can be done only through the preaching and teaching of the Word.

What follows we will ask what are or ought to be the unique characteristics of ministry training in response to our context, and on the basis of our identity as Reformed Christians. The question is: how are we to equip people for ministry? Here again, our attempt will be to take into account both biblical priorities as well as contextual particularities.

3. Seven Characteristics←⤒🔗

A. Equipping the Whole People of God←↰⤒🔗

If ministry belongs to the people of God (the laos from which the term ‘laity’ is derived), as was demonstrated earlier, then it is necessary that training for ministry should aim at equipping all the people of God. Of course, it should not be thought that formal theological education is the only valid form of training people for ministry. In fact, it may be assumed that in every congregation some facility exists by way of church education programmes to train people. The quality of these will vary from congregation to congregation.

But something less ad hoc is desirable for more effective ministry. It is a positive thing that theological institutions themselves have awakened to this need. Traditionally, theological institutions, following patterns borrowed from the West, have concentrated on professional training rather than lay training. However, as lay involvement in ministry increases, this pattern has to change. According to Derek Tan, “institutions that have a ‘full-time calling’ tag for admission portray themselves as elitist clubs in catering to a selected few and not the whole.”7

It is my observation that in Asia as well as in the West, more and more theological institutions have begun to recognise the need for equipping the laity. Many institutions have evening classes that seek to equip people in ministries that are traditionally reserved for the laity. These include children’s educational ministries, youth ministries, etc. Often with a minimum of biblical-theological content free of theological jargon, these courses aim at producing lay practitioners rather than professional scholars. Not only the content but also the time of instruction is adjusted to suit those whose day-to-day occupation lies outside the church.8

Alternative models of theological education have emerged in response to the perceived deficiencies of the traditional model. Ivan Satyavrta remarks that the church in India has become “disillusioned with traditional residential institution-based methods” and is looking to other non-formal and informal training programmes.9 Dissatisfaction with traditional theological institutions is a recurring theme in discussions on theological education. There is a perception that seminaries are not training effective leaders for ministry. Instead of nurturing students for ministry, it is felt that the heavy academic load and critical approach of these institutions destroys the spiritual vitality and enthusiasm brought by entering students.10

The recognition that theological education need not conform to a set pattern is one of the most refreshing developments in the field.

Programmes that seek to equip the laity are being actively pursued by various agencies. Extension courses are prospering all over the world. The TAFTEE (The Association for Theological Education by Extension) programme in India is a case in point. TAFTEE has revolutionized lay training (and also is involved in training of professionals). Peter Pothan defines TEE as “a movement ... intended to theologically train all the people of God for ministry in the church and the world.”11 He asserts, “we should believe that all God’s people are called to minister and therefore be involved in training them to discover their gifts and use them in ministry. This is not training for an elite few, for a minuscule leadership, but for all members of the church.”12 He sees the “broadening” of the traditional concept of ministry as “the most valuable contribution TAFTEE can make in India.”13

B. Ministry-Oriented←↰⤒🔗

Theological education in what is called the University Model is still the favoured one in Asia as it is all over the world. In this model, theological education is by and large still measured by criteria heavily favouring academic performance and intellectual gain. This bias is due to at least two factors. One is the intellectual model of ministry training inherited from the West (especially in the Reformed tradition) where the emphasis has been on knowing the right theology, based on the assumption that right knowledge will automatically produce good ministers. The second factor contributing to this intellectual bias is the popular understanding of education in Asia as primarily book knowledge. Rote knowledge of a certain amount of facts usually acquired just before the exam season is sufficient to consider a person educated. Character formation, aptitude, skills, interest in the subject, etc. were either never measured or not given much weight. Even practical lessons and examinations linked with subjects such as science were often considered irrelevant to life. Degrees, rather than the ability to apply knowledge, were considered the mark of education, and formed the stepping stones for “higher education.”

Theological training in Asia must intentionally make equipping for ministry its main concern. Academic preparation is only part of this equipping. It cannot be denied that there is a decidedly scholastic leaning in our programmes. In effect, producing mini-scholars becomes the hidden agenda of the institutions and the mark of their success and respectability. Teachers themselves encourage this tendency. The assignments required promote analytical thinking rather than reflective thinking. Cognitive knowledge is emphasised and measured (valued) more than experiential or practical knowledge. The results of this misguided emphasis are obvious. Graduates of theological institutions are often unable to handle real ministry situations in the field. Too many – even those who are particularly gifted for an academic career – see more and higher degrees as the standard of success. Sometimes engagement in ministry is undertaken only to fulfil the admission requirements for the next degree programme.

There must be a deliberate turning to personal and ministerial formation in the programmes offered. Such a shift or change of course will not come easily. The ministry implications of each subject – not just the practical ones – must be explored. Assignments given must help them to become familiar with contextual ministry issues, and in a format suitable to ministry needs. For example, assignments for biblical and theological subjects could include sermon writing rather than research papers. Case studies where theological reflection and application have to be employed are useful in reinforcing truths learned in a practical manner. The relevance of theological learning to ministry must be immediately evident to the student so that he is able to integrate classroom learning with field realities.

C. Strong Biblical-theological Content←↰⤒🔗

There is often a misunderstanding that biblical or theological subjects are not very relevant to ministry. Or that the theological curriculum ought to be watered down considerably in order to bring out the ministry emphasis in training. Japanese theologian Akio Hashimoto observes that the length of time for theological training is getting shorter and shorter, and the training itself is getting more and more “practically” oriented.

As a result, he says,

many seminaries and theological faculties nowadays are content with a rudimental level knowledge of the (biblical) languages – that is, if they do not discard them altogether.14

What is true of languages can equally be true of studies in systematic theology, for instance. It is my observation that in many institutions in India, courses in theology, especially systematic theology, have been reduced to the very minimum. This is a mistake. Training for ministry is not just about imparting some skills or techniques. Without theological foundations, ministry will deteriorate to human opinions and ideas. Carver Yu correctly points out the lack of theological depth in favour of pragmatic programmes: “The church, the modern evangelical church in particular, has become a mere ensemble of ministries driven by strategies for growth.”15

D. Responsive to the Church←↰⤒🔗

There is a strong sense among evangelical institutions that ministry training must be church-oriented. The second of the values noted by the ICAA Manifesto is titled “Churchward Orientation”, and may be quoted here:

Our programs of theological education must orient themselves pervasively in terms of the Christian community being served ... At every level of design and operation our programs must be visibly determined by a close attentiveness to the needs and expectations of the Christian community we serve. To this end we must establish multiple modes of ongoing contact and interaction between program and church, both at official and at grassroots levels, and regularly adjust and develop the program in light of these contacts. Our theological programs must become manifestly of the church, through the church, and for the church.16

'It is generally recognised', says Brian Wintle, Secretary of the Asia Theological Association (India), 'that there is need for closer co-operation between Church and Institution in the design and implementation of theological curricula.'17

This need for church orientation in theological education is acknowledged also by mainline churches and theological institutions in India.18 A Consultation of mainline church leaders and theological educators, held under the auspices of the National Council of Churches of India (NCCI) in August 2002, complained that “participation of the Churches in the Serampore System (the Senate of Serampore College) is minimal,” and strongly recommended a greater role for churches in the administration of theological education. It categorically stated that “the present theological system is not adequately catering to the needs of the Churches.”19

There are several reasons for this call for church orientation of theological education. For too long churches and theological institutions have been going their independent and separate ways. As a result, there is a chasm between the two. Churches complain that theological institutions are not training candidates for ministry, while theological educators see churches as too outdated and traditional. Theological institutions need to listen to the church, it is felt, because the church provides the primary “market” for their “products.” A large number of theological graduates find their vocation in the context of the institutional church. Secondly, in this call for closer co-operation between the two entities can also be heard a desire to check the tendency of theological graduates abandoning church ministries for more lucrative positions in para-church or transdenominational agencies. Many of these agencies have no local roots or controls. Their agenda is set from abroad, and foreign (mostly western) personnel and financial resources control their administration. That is to say, their theology of ministry is far from contextual.

From a reformed point of view, this emphasis on the church in theological education is a very welcome one. In fact, it is worth noting that it is not only the theological institutions that are to blame. It has been my experience in India that churches are only marginally involved in the recruitment, care and development of the student. The tendency is to leave everything in the hands of the Seminary. The tragic fact is that sometimes it is impossible even to get an objective evaluation of an applicant from local pastors. This situation must change if we are to equip people for ministry in the church. Carver Yu very correctly observes:

... (T)he church no longer as before covetously guards her authority to nurture, call and prepare lay persons for ministry; instead she expects seminaries to train leaders for her consumption without selecting the best from her congregation to be sent to seminaries for equipment. ... The church sees herself more as an employer rather than as a gardener for whom the seminary is her seedbed to grow leaders for ministry.20

Without doubt there is a great need for co-operation between churches and theological institutions in equipping people for ministry.

E. Missional←↰⤒🔗

It was noted earlier that the Asian context is one of religious pluralism. Revival of traditional religions or the growth of religious fundamentalism has made it impossible for Christians to forget that we minister at the cutting edge. In one sense, rise of militancy has brought the issues in mission to sharp focus. It has now become impossible to ignore the confrontation between Christian faith and other faiths.

Too much or the wrong kind of emphasis on church-orientation (as discussed above) can be dangerous. Church orientation may easily turn into an unhealthy church-centredness. Many traditional churches have no concept of mission to speak of, and they exist only for communal or similar interests. Following the lead of such churches, training for ministry can simply become maintenance-oriented rather than mission-oriented; the emphasis will be on maintaining the status quo.

F. Concern for the Kingdom of God←↰⤒🔗

I have isolated this from the concern for the church and mission in order to highlight it. Here we want to affirm a Reformed emphasis, and indeed a biblical concern, that ultimately we are called to proclaim the Kingdom of God even as the Lord Jesus did. We strongly believe in the sovereignty of God over all things, and this truth must be reflected in our ministry. The danger exists that ministry is made too church-oriented. In fact, even our understanding of mission is truncated. Most evangelical churches have only a narrow understanding of mission, defined primarily in terms of evangelism and church planting. J. Jeyaraj, an experienced theological educator in India, states the problem succinctly. Talking to a group of theological educators, he says:

One major problem with many of us is (that we think) theological training is only to work in the churches. We have a limited understanding of God’s mission. We are satisfied with producing ‘pujarees’ (priests) to conduct the worship lively, pray and counsel the congregations and plant churches. We need to raise the important question – What is the mission of the church? Should the church be satisfied with worship services, prayer meetings, orphanages and evangelistic campaigns? Is she not called to establish justice, welfare, and peace?21

Issues of justice and righteousness are not part of a liberal agenda to subvert the church as some evangelicals fear. These issues are at the heart of Christ’s mission. A pastor who neglects justice issues in his congregation, or he simply advises that people should only and always bear injustice, is not biblically equipped for ministry.

Yet the question remains whether this is rightfully the place of theological education. More theologically liberal institutions emphasise this aspect routinely, and at times in an unbalanced way. It is encouraging that some evangelical institutions have gone beyond the traditional role of theological institutions to equip especially the laity such as businessmen, administrators and other Christian professionals with an understanding of Christian vocation. This innovation is to be welcomed. However, a question may be raised whether the already crowded theological schools can accommodate another stream.

G. Proclaim Grace←↰⤒🔗

To proclaim the gospel, whether to a Christian congregation or to those outside the church is to proclaim grace. Yet, equipping people for this task is not an easy one. This is partly because of the particularities of our context as we discussed them earlier. Asian cultures, with their strong emphasis on filial duty, caste dharma, authoritarian discipline, and a strong sense of loyalty to one’s own group all stand in the way of experiencing, practising and preaching grace. In our preaching, we find it easier to lay down the law (literally) than to motivate people to live in grace. Theological students and communities must be encouraged to exercise responsible freedom than to conform to a set of rules and regulations out of fear of punishment. But this a step that cannot be compromised.

Bibliography

- Arles, Siga. “Governance of Theological Education – Patterns and Prospects.” Journal of Asian Evangelical Theology 14/1 (June 2006): 53-69.

- Arles, Siga, Ashish Chrispal and Paul Mohan Raj, eds. Biblical Theology and Missiological Education in Asia: Essays in Honour of Rev. Dr. Brian C. Wintle. Bangalore: Asia Theological Association (India) / Theological Book Trust

- Arles, Siga and others, eds. The Pastor and Theological Education: Essays in Memory of Rev. Derek Tan. Singapore: Trinity Christian Centre / Bangalore: Asia Theological Association, 2007.

- Arles, Siga, and Brian C. Wintle, eds. Striving for Excellence – Educational Ministry in the Church: Essays in Honour of the Rt. Rev. Dr. Narendra John. Bangalore: Asia Theological Association, 2007.

- Chacko, Mohan. “An Evangelical Vision for Contextualised Theological Education in India.” In H. Vroom and J.D. Gort, eds. Festschrift for Prof Dr. Anton Wessels (in Dutch).

- Ferris, Robert, W. Renewal in Theological Education: Strategies for Change. Wheaton, IL: n.p., 1990.

- Hrangkhuma, Fanai. “Missiological Education in India: Journey to Become Academically Authentic and Contextually Relevant.” Journal of Asian Evangelical Theology 13/1 (June 2005): 103-20.

- Jeyaraj, Dasan. “Theological Education for Missionary Formation.” Journal of Asian Evangelical Theology 12/1-2 (June-Dec 2004): 139-68.

- Wingate, Andrew. Does Theological Education Make a Difference? Global Lessons in Mission and Ministry from India and Britain. Geneva: WCC Publications, 1999.

Add new comment