The Belgic Confession in the Northern Netherlands

The Belgic Confession in the Northern Netherlands

It is enlightening to see how the Belgic Confession (1561, author Guido de Brès) historically attained its confessional status in the Netherlands. We observe a dynamic development of the ecclesiastical and political situation in the Netherlands after 1560. These are the years of the start of the rebellion against Spanish rule, which resulted, in the northern Netherlands, in the 80 Years War. Protestant church life came more and more out in the open, obtained freedom of movement in different places, and organized itself.

During the first years of the revolt, the Heidelberg Catechism (1563), translated from German, was the most important confessional document for the Dutch speaking Reformed believers, not the Belgic Confession (hereafter often abbreviated as the BC), originally written in French in 1561, but quickly translated into Dutch. When the Reformed leaders of the Netherlands gathered together as a Synod in Emden, Germany, in 1571, they did choose the Belgic Confession as a binding confessional statement. Hence the pronouncement that subscription to the confession of the Dutch churches was highly recommended, in order to demonstrate the unity in doctrine between the Dutch churches (art. 2). This pronouncement was regarded as applying to all who served in Dutch churches both outside Emden and after Emden.

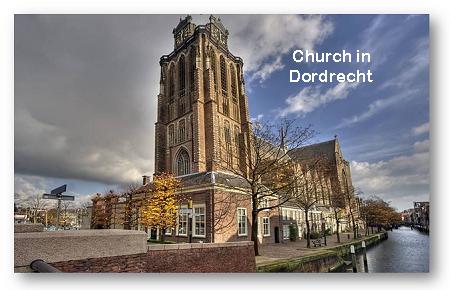

After large parts of the province of Holland (the modern provinces of North and South Holland together) chose the side of the revolt, the Reformed churches held in 1574 a Provincial Synod (hereafter often PS) in Dordrecht. The BC received there a constitutive character. Agreement by subscription was made mandatory for school teachers as well as ministers.

Shortly hereafter the Classis Walcheren, an island in Zeeland, ratified a subscription text for the BC, the first in the northern Netherlands. This confession of faith of the Christian churches of the Netherlands is called “equivalent to the Word of God in all points.” Therefore all ministers are required to promise to hold to it, and, as far as possible, to resist everything which is opposed to it.

Four years later, in 1578, a General Synod was held in Dordrecht. There the decision was made that Professors of theology as well had to subscribe to the confession, and that it would be good if elders would do so as well.

A following General Synod met in 1581 in Middelburg. Signing official adherence to the confession was deemed required, not just for ministers, but also for deacons and school teachers. The Synod expressed the desire to have an improved text of the confession available. At the last General Synod of the 16th century, that of The Hague 1586, the Synod pronounced that ministers who refused subscription would thereby de facto be suspended from the ministry by their church council or classis. Those who continued to refuse to subscribe would be dismissed from the ministry. Further, school teachers are given the choice between signing the BC or the Heidelberg Catechism.

Toward the end of the 16th century we see hereby the development of a clear set of church pronouncements regarding the status of the Belgic Confession as the official church confession, next to the Heidelberg Catechism. By means of making obligatory subscription to the confession across the board, the Reformed churches sought to ensure a reliable corps of ministers in their midst.

Provincial and Local Level⤒🔗

At the provincial and local level the situation surrounding the reception of the Belgic Confession was considerably more complex. In many cities, refugees from the southern Netherlands were the most avid supporters of the Belgic Confession, but not everyone was so enthusiastic.

We look first at the situation in South Holland, one of the central provinces of the revolt against Spanish rule.

In the largest and most important city of Holland, Dordrecht, one of the ministers, Herman Herberts, supported by the city government, rejected the binding character of the BC. In the end, Herberts professed his agreement with the BC, however without signing it. He was in the meantime engaged in talks with the church of Gouda, and moves there.

In Leyden the city government was of the opinion that everyone who accepted the Bible as God’s Word should be welcome at the Lord’s Supper, and not just those who confessed the BC. This was a direct challenge to the local Reformed church council, with its confessional standpoint about the church. In these cases we see that the Reformed churches in South Holland maintained the synodical series of pronouncements with regard to their ministers, and tenaciously wish to hold on to the demand for subscription to the BC as a sign of unity in doctrine, but that in most of the cities of this province this intention of the churches could not be carried out consistently due to political interference at the local level.

Next we look at the situation in North Holland, a second central area of the revolt. When we look not only at the Synods and the Classes, with respect to the introduction of the BC in the province of North Holland, but also at the local circumstances, then we notice some big differences.

A city such as Amsterdam, for example, conformed to the doctrinal policy of the Provincial Synods. The ministers of Amsterdam who received calls after 1600 furthered the socially acknowledged confessional position of the church. The pro-Reformed city government valued the Reformed church as a harmonizing institution within society. Just like Dordrecht in a somewhat later phase, Amsterdam offered a successful integration model of cooperation, whereby the public Reformed church got the opportunity to fulfill its role in urban culture.

In Haarlem, to look at another city in North Holland, the situation is quite different from Amsterdam. The Reformed church adhered to the signing of the BC, but the Haarlem city government tried to act as neutral as possible on this issue. With respect to the schools in the city, the Haarlem magistrate persisted in maintaining a non-confessional school system. However, in Haarlem there occurred a major about-face after the Synod of Dordrecht 1618-19. The schools were now regarded confessionally as an extension of the Reformed church. Signing the confession became obligatory for all teachers.

The province of Utrecht provides an interesting case. Before the Reformation, Utrecht was, due to it being the seat of the Bishop, ecclesiastically the most important city in the northern Netherlands. It lasted till the national Synod of The Hague 1586 until all the Utrecht church officers signed the BC and all ministers preached every Sunday from the Catechism.

Up to the end of the 16th century, the province of Overijssel remained an area of the front in the war between the Dutch troops of the revolt and the Spanish. In the countryside the Reformation went slowly. Former priests who accepted the Reformed doctrine could administer the Word on condition that they sign the confession and the church order. The BC accompanied the transition to a Reformed church federation. The reception of the BC in Overijssel took place gradually, and with discussion.

The Confessionalizing Process←⤒🔗

The process of confessionalizing, moving within Protestantism toward Calvinism, is clearly illustrated by the case of the province of Overijssel.

Before 1566, the three cities on the IJssel river, Kampen, Zwolle, and Deventer, had together asked permission from the Governess of the country to hold services in accordance with the Augsburg, that is, the Lutheran confession. Only later did the churches of Overijssel formulate their confessional unity as one of being bound to the Belgic Confession. From then on they regarded the BC, with the Heidelberg Catechism, as the confessional foundation for church life.

As far as revision of the original Belgic Confession is concerned, the Reformed churches in a number of provinces were not in favor of it. There was hesitancy in different provinces to consider modifying and improving it. But a final revision at the national Synod of Dordrecht, 1618-19, did make definitive changes to establish the official text.

International Recognition←⤒🔗

Regarding international recognition of Protestant confessions, the Reformed churches of France submitted a request to the Dutch churches to mutually examine each other’s confessions. In response, the churches of North Holland consulted the churches of South Holland. The proposal was made to accept each other’s confessions across national boundaries. The Belgic Confession was seen here in the Netherlands, just as the French confession in France, as a particular form of expression of an identical international Reformed Protestantism. The BC was not seen by the Dutch churches as the only possible Reformed confession in Europe.

In South Holland we see another, far-reaching request, that is, that the Reformed churches sign the Lutheran Augsburg confession, while the supporters of the Augsburg confession sign the BC. The request was submitted to come to mutual church union; a request for mutual, inter-confessional recognition, based on an ecumenical motivation. While this did not finally take place, it indicates the way many Reformed churches in the Netherlands valued the Lutheran confession.

Summary and Conclusion←⤒🔗

We come to the following conclusions: Otherwise than the history of the editions of different confessions might lead one to imagine, in the northern Netherlands, not just the Heidelberg Catechism, but the Belgic Confession as well plays a central role in defining a Reformed identity.

Research on the development of confessional identity should pay close attention to developments in society and the government at the level of the cities and the countryside in the northern Netherlands, which helped determine the character and the tempo of the Belgic Confession’s function in church life.

Confessional identity came to the fore visibly in the northern Netherlands under the pressure from social, political, and military circumstances. For example, the voice of exiles from the southern Netherlands contributed demonstrably to the wholehearted acceptance of the Belgic Confession. Church assemblies formulated a powerful confessional concept for the public Reformed church and its office-bearers. But because every city and region had its own history of reformation, the impact of the Belgic Confession on the reformation in the northern Netherlands was varied.

Ecclesiastical and political organs negotiated with each other about carrying out reformation at the local and regional level. In some cities there was a high degree of tension and friction, particularly where the authorities protected ministers against church disciplinary measures of a confessional character.

The Reformed churches pursued the objective of establishing confessional schools, with the consequence of an obligatory signing of the Belgic Confession for teachers. Up until the Synod of Dordrecht 1618-19, this resulted in tension in various localities.

In the northern Netherlands, Reformed churches in many provinces conducted negotiations very early on regarding objections to revisions of the Belgic Confession. They also began early to talk to one another across provincial lines regarding international mutual recognition of national confessions, in particular regarding the Reformed churches of France, as well as regarding inter-confessional unity with Lutherans.

Add new comment