Adapa and Abraham: The World of the Old Testament

Adapa and Abraham: The World of the Old Testament

The Assyriologist Jean Bottéro (d. December 15, 2007) described the religiosity of the Mesopotamian peoples as a prehistoric religion without holy scriptures, religious authorities, dogmas, orthodoxy, orthopraxy, or fanaticism, and it evolved sporadically, depending upon the culture of which it was only the reflection and on the time and events. (Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia, 6)

Although the deities had different names, what is said here of the religious world of Mesopotamia is just as true for that of Canaan: no religious authorities, no dogmas and no orthopraxy – an ideal religion for post-modern people too. It was right in the middle of this that Israel lived, that special people, with its one God and its exclusive pretensions. The religious activities of the neighbouring peoples continually exerted a powerful attraction.

It is a fascinating world, also for people studying it in completely different times and in a completely different culture. In the Akkadian course which was completed last year after (on urgent request) a year’s prolongation, I was privileged to have a classics graduate participating. This student found it to be a captivating and revealing experience to discover that the Greeks and Romans had not invented everything themselves.

In The Netherlands the study of Akkadian seems to be declining. My impression is that in the rest of the world things look a little rosier. What has been published during the last decades is without a doubt very impressive. Important to specialists are the editions of texts which had not been published previously, new editions of known texts (e.g. the Epic of Gilgamesh), and further sign lists, dictionaries, and grammars.

For people outside the profession, including theologians, the volumes of up-to-date translations are of special importance, like The Context of Scripture (COS), that replaces Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET). When ANET was first published everything fitted into one volume. COS requires three. And to top it all, a number of items from this list is available digitally, sometimes at a small cost, sometimes even free of charge. An honourable mention should be made of the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, to be downloaded without cost from the website of The Chicago Oriental Institute. Not only does this save almost a metre of space on the shelf and lighten one’s budget, being digital means unlimited possibilities for searching in this dictionary.

Fascinating World⤒🔗

A fascinating world and yet at the same time so different from what we know of the people of Israel. For the moment I position myself behind the words so different. So different, but how different? A little bit different or completely different? That is the exciting question that has kept us occupied for more than a hundred years. The answers tend to vary considerably.

Personal starting points, convictions and presuppositions appear to play a major role. They direct the way in which you look at the given data. They can sharpen the perception but can also cloud the perception. Everybody is at risk of being hindered by their starting points, convictions, and presuppositions.

That is true for people who consider the Old Testament to be part of God’s revelation and therefore the redeeming word and the first and last word in their lives. It is just as true for people who have little or no personal and/or religious affinity with the Old Testament. It is apparently not so easy to read texts from another culture and from other times with an open mind. This can be well illustrated by means of a short text, the Tale of Adapa. It is dated back to the second millennium before Christ. The most important manuscript originates from the fourteenth century Amarna in Egypt (which tells us something about the distribution of this text).

Tale←⤒🔗

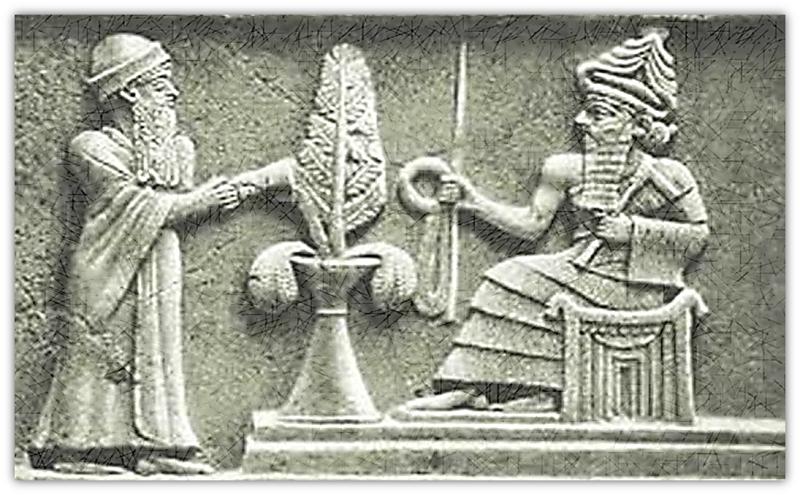

The tale is quickly told. While at sea, Adapa, a faithful priest of the god Ea in the temple of Eridu, is caught off guard by the South Wind and his boat is overturned. He utters a curse that breaks the South Wind’s wing. Anu, the supreme god of the sky, is furious and summons Adapa to appear before him. Before appearing in heaven before the sky god, Adapa receives detailed instructions from Ea, which should guarantee a favourable resolution.

Anu is so impressed by Adapa’s defense that he decides to welcome him as a god. Adapa, however, obeying Ea’s instructions, denies the bread and water of life which Anu offers him. For Adapa assumes, based on Ea’s instructions, that this is the bread and water of death. Anu laughs meaningfully and sends Adapa back to earth. He has missed out on the chance of immortality.

William Hallo, renowned for contemplating the methods of text comparison from the Bible and from the Ancient Near East, concludes the brief introduction preceding the translation in COS with the words: This myth provides an aetiology of death and thus a parallel to the story of Adam in the Bible. (COS, 1:129.)

Hallo defines an etiology as the 'explanation of a presently observed condition by appeal to an imaginary one-time event in the past.'Scriptura, 87 (2004): 267

In my opinion Hallo reads the Adapa story too much from the starting point of Genesis 3. If the Adapa story is read on its own, Hallo’s characterization “etiology of death” is questionable. Adapa is an inhabitant of the city of Eridu. In other words: he is not someone standing at the origin of the history of mankind. Furthermore, there are little or no indications that what happened to Adapa is decisive for the whole of mankind.

The portrayal of an individual being granted immortality, with no consequences for mankind as a whole, is well-known in Akkadian literature. This is exactly what happened to Atrachasis, the man who survives the great flood and who, together with his wife, becomes immortal, yet no-one else.

The parallel with Adam also does not hold water. The similarity, it is argued, is to be sought in the themes of food and immortality. Superficially it is possible to point out these themes, but as soon as you dig deeper, the differences become apparent. The most important one regards obedience. Adam misses out on immortality because of his disobedience. Adapa ruins his chance of immortality because of his obedience.

Questions←⤒🔗

At the same time the tale raises questions as to the position of the gods who play such an important part in it. Why does it end so unfortunately for Adapa? Is Anu too clever for Ea, and what does that do to Ea’s reputation as the god of wisdom? Or did Ea mislead his pupil Adapa so that he would not lose his priest to the world of the gods? And what does that say about the friendliness of the gods? If I understand the story correctly, the conclusion would seem inevitable that the god Ea knew very well what would happen during the meeting with Anu. Thus he gave Adapa a wrong impression of the matter, causing Adapa to miss the chance of immortality and promotion to the world of the gods. Without compromising my respect for Hallo, I would have to conclude, as others do, that the characterization of the Adapa story as an etiology of death is unconvincing, and that speaking of a parallel with Adam is taking it too far.

Overall we can conclude that in Ancient Near Eastern literature still no convincing parallel has been found for the story which Christian theology calls “the fall into sin”. The words from more than 20 years ago by the aforementioned Bottéro, still ring true:

To this day, no one has convincingly shown the least trace of a comparable account, even in the inexhaustible treasures of ancient Mesopotamia, by which the Yahwist author or his predecessors could have been inspired — even in the way the authors of the exordium to the Priestly Document borrowed something, no matter how indirectly, from the Babylonian cosmogonies (...)The Birth of God, 175

Hebrew←⤒🔗

That Ancient Near Eastern world, so different and at the same time so fascinating, remains well worth studying. But the principal part of my work at the University is of course teaching the Hebrew language. I am happy with strategic choices made by the Theological University on the terrain of languages: Languages for Theology. I see it as my mission to prepare students for a professional and respectful manner of reading the Bible. Even after thirteen years – to my own surprise – it is still exciting to make a fresh start each year with a new group of students and teaching them to read and write Hebrew from scratch.

Presuppositions and convictions can be an impediment in the study of Hebrew grammar too, just as they can with reading and comparing texts. Once in a while I even catch myself doing it. For years I was somewhat surprised by a remark in the Hebrew Grammar of Joüon-Muraoka, that the word group mal’ak Yhwh probably also could mean “an angel of the Lord” (JM §139c).

It seemed to me superfluous to seriously consider this possibility. That changed when I dived into the material and made some interesting discoveries (which others had already done long before me):

- Comparison and descriptions of identical stories in different Bible books make it clear that the angel of the Lord can just as well refer to a normal angel. The angel called “the angel of the Lord” in 2 Kings 19:35 is simply “an angel” in the same story in 2 Chron.32:21. “The angel of the Lord” that appeared to Moses in the burning bush (Ex.3:2) is called just “an angel” by Stephen in Acts 7:30.

- The practice of translation in the Septuagint, the oldest Greek translation of the Old Testament, corresponds with this. In a new episode the Hebrew phrase is first presented as “an angel of the Lord” and thereafter as “the angel of the Lord”. The NBV (New Bible Translation in Dutch) follows this translation practice. A similar pattern can be found in the narrative parts in the Greek texts of the New Testament (e.g. Matthew 1:20, with the indefinite article, and 1:24, with the definite article).

We are hereby confronted by a well-known phenomenon from Hebrew Grammar: a character is grammatically determined the very first time he appears in an episode (JM §137n). In other languages, including Dutch and Greek, such a new character is first grammatically undetermined and subsequently determined.

In other words, careful reading of the Bible text makes it clear that it is incorrect to presume that the phrase “the angel of the Lord” refers to a specific angel, or that it refers to the same angel repeatedly. The identity of this messenger must be determined in the specific case on the grounds of the context of the text.

Five Years←⤒🔗

For more than five years I have now occupied myself with the development of a new teaching method, which I hope will introduce the students to principles of the Hebrew language in a contemporary and attractive manner. In most cases students who now start the course have a very different education background than those of thirty years ago. Being a lecturer, I cannot ignore this problem.

The goals I have set myself in this teaching method are the following:

- to arrange the process of becoming familiar with the Hebrew language in such a way that students can read texts from their Hebrew Bible at an early stage (every year I am again lightly euphoric when we are able to read the first verses of the Bible after some five weeks or so, “in the wild” – not tamed by the artificial world of a textbook);

- that the students learn to see the verb forms in such a way that the building blocks of the form divulge their information about root, stem, form, etc. bit by bit;

- the removal of terminology that does not belong in a Hebrew textbook, including terms and notions from the grammar of languages unrelated Hebrew.

It is a textbook, which is by no means the same as a grammar. While writing it I constantly had to repress the urge to make exhausting enumerations. I had to teach myself to put myself in the student’s place: the student who has a text in front of him and has to know what tools to use in order to dissect the information into forms and structures. Many a time this transition into the student role resulted in my throwing a concept into the bin and having to start all over again.

The greatest challenge was formed by the verbal forms. I had been trying out an approach for a few years that turned out to be far from ideal. Then I was placed before the challenge at the theological seminary of Kiev of teaching the Hebrew verb in only two weeks. (Can you imagine it? The lecturer teaches in English, which is translated simultaneously into Russian and we are talking about Hebrew...) I seized that challenge to start completely anew one more time.

The chosen approach turned out to be effective. I am now busy ironing out the last wrinkles in this approach. Students are more than happy to assist. For every mistake a student discovers, a euro goes into a jar, for a worthy cause at the bakery once the course is completed.

Second Year Students←⤒🔗

With the second year students we are at this moment reading Joshua 24. I chose that chapter for a specific reason. In modern research, major parts of the history of the people of Israel are dismissed to the realms of fiction. David and Solomon are pruned, the Exodus as a historic event dangles in the air, and Abraham is a legendary figure. What I noticed when reading Joshua 24 is how God relates the earliest moments of the history of his people in the first person: “I took your father Abraham from the land beyond the River”, “I sent Moses and Aaron...”, “I brought your fathers out of Egypt.” The Lord, the God of Israel, is the director of these events and associates his credibility to the history that He made with His people. You dismiss that if you declare these events to be non-historical, and in this way you also lose that this God saves and sets free. It is always worthwhile to look closely at the way in which a history is told, and that is true also in this chapter. Small details are often telling, but they can easily escape your notice.

Long ago your forefathers, including Terah the father of Abraham and Nahor, lived beyond the River and worshiped other gods. But I took your father Abraham from the land (...)

Abraham Idolater←⤒🔗

Abraham was an idolater, as was his father and his brother. He grew up in that world “without holy scriptures, religious authorities, dogmas, orthodoxy, orthopraxy, or fanaticism”.

An irresistible urge exists to improve the biblical image of Abraham. That urge of all ages. The Book of Jubilees (dating to the second half of the second century BC) tells the book of Genesis and the first book of Exodus all over again.

Concerning Abraham the story is then told as follows: the young Abraham is but a teenager when he distances himself from his father as far as the worship of idols is concerned (11:16). Some fifteen years later he again questions his father critically on the futility of idolatry and calls on him to worship the God of heaven (12:1-8). When Abraham is sixty he, without anyone noticing, sets fire to the temple of the idols (12:12-14). The Book of Jubilees leaves no doubt about it: Abraham was the first reformer. No wonder God’s choice fell upon Abraham.

Abraham was an idolater when God came to fetch him. That is history. “Abraham as a reformer since childhood”: that is another way to turn Abraham into a legendary figure. However, history teaches us that it is and remains an inexplicable miracle that God plucks idolaters out of their surroundings and gives them a new life.

We have a beautiful word for this: grace. Maybe we should learn to speak respectfully, just as the apostle Paul did: the issue here is “the glory of the grace of God” (cf. Eph.1:6). If we humans are asked to reproduce the story of Abraham in our own words, then it can suddenly become a story in which Abraham steals the show. If we let God speak, we see that it is He who shines and we are impressed by His grace.

Grammar, grace and glory are, as far as I am concerned, the words that will continue to govern my work at the university. I would like to thank you, the synod, and the University Board for the trust you have placed in me.

Add new comment